The Depopulation Bomb Isn’t Ticking, It’s Overblown

What the overpopulation panic of the 1960s and 70s can teach us about the underpopulation panic of today.

In the 1960s and 70s, as the global population was growing by leaps and bounds, prominent intellectuals, institutions, and political leaders, from the United Nations, to the Club of Rome, to President Richard Nixon, warned about the looming crisis of overpopulation. Today, with birth rates falling around the world, a growing number of thought leaders foretell the precise opposite.

Sharing a stage with Chinese business magnate Jack Ma, Elon Musk said, “the biggest problem the world will face in 20 years is population collapse.” Ma heartily agreed, calling the “population problem” a “huge challenge.” They aren’t alone. These sentiments are echoed, with varying degrees of grandiosity, by Silicon Valley tycoons like Peter Thiel, right-wing populists like J.D. Vance and Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, conservatives like Niall Ferguson, and religious leaders like Pope Francis. And it’s not just folks on the political right. Non-partisan think tanks like the Centre for International Governance Innovation host conferences with titles like “Empty Planet: Preparing for the Global Population Decline.” Prestigious journals like The Lancet publish research with headlines such as “Dramatic declines in global fertility rates set to transform global population patterns by 2100.” The New York Times runs editorials trying to reframe population growth as a progressive issue. Put simply, concerns over a coming population collapse are, unlike young people, mounting.

This raises two important questions. How sure are we about a future population crash, and would a decline in the population necessarily be a disaster for humanity? On both scores, there is ample reason to be skeptical.

How it Started

In the year 10,000 BCE, the world population was an estimated 4 million people, smaller than modern-day Douala, Cameroon. By the year 1 CE, the global population stood at around 190 million. It reached 500 million in the 1600s, and 1 billion in the 1800s. By 1928, it was 2 billion. By 1960, 3 billion. And by 1974, 4 billion. Given this seemingly exponential growth, combined with a rapidly industrializing world, it’s no wonder folks started to worry.

The economist and demographer Thomas Malthus was the first to sound the alarm in his 1798 pamphlet, An Essay on the Principle of Population, in which he warned that population growth would eventually lead to widespread famine and resource depletion. 150 years later, William Vogt’s Road to Survival (1948) and Fairfield Osborn’s Our Plundered Planet (1948) breathed new life into Malthusianism and inspired Hugh Moore (the founder of Dixie Cups) to publish the 1954 pamphlet The Population Bomb is Everyone’s Baby. But it wasn’t until biologists Paul and Anne Ehrlich wrote their 1968 book, also titled The Population Bomb, followed by the Club of Rome’s famous Limits to Growth (1972), both prophesying societal collapse, that the panic about overpopulation, well, exploded.

The predictions of what was in store for humanity were nothing short of calamitous. Harvard biologist George Wald said that “civilization will end within 15 or 30 years unless immediate action is taken against problems facing mankind.” Ecologist Kenneth Watt told Time that because of nitrogen buildup, “it’s only a matter of time before light will be filtered out of the atmosphere and none of our land will be usable.” Denis Hayes, one of the founders of Earth Day, lamented that “It is already too late to avoid mass starvation.”

Paul Ehrlich in particular was a perpetual motion machine of real doozies. He asserted in a 1970 interview that the “population will inevitably and completely outstrip whatever small increases in food supplies we make.” He went on to say “the death rate will increase until at least 100-200 million people per year will be starving to death during the next ten years.” In an essay he wrote the previous year, Ehrlich declared “Most of the people who are going to die in the greatest cataclysm in the history of man have already been born.” Between 1980 and 1989, Ehrlich foretold that this “Great Die-off” would claim 4 billion lives around the world, including 65 million Americans.

In response, movers and shakers put these fears into action. John D. Rockefeller III poured a chunk of his family’s vast wealth into confronting population growth. Richard Nixon addressed Congress in 1969, saying, “One of the most serious challenges to human destiny in the last third of this century will be the growth of the population. Whether man’s response to that challenge will be a cause for pride or for despair in the year 2000 will depend very much on what we do today.” China began substantial efforts to halt population growth, culminating in the One-Child Policy that began in 1980 and ran for 35 years. Perhaps most consequentially, international aid organizations, such as the World Bank, the USAID, and the Ford Foundation took a keen interest in population issues, not only providing considerable funding across the world for family planning, but often pegging the amount of aid developing countries could receive to reaching various population control benchmarks.

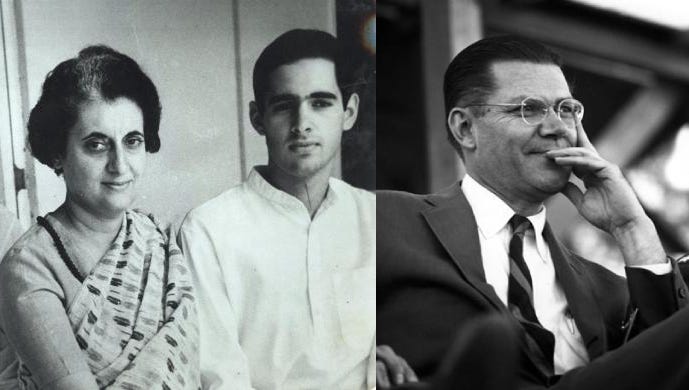

Robert McNamara, who ran the World Bank after serving as Secretary of Defense for John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, said in 1969 that the bank would not finance developing-world healthcare “unless it was very strictly related to population control, because usually health facilities contributed to the decline of the death rate, and thereby to the population explosion.” President Johnson, speaking to an advisor about the famines in India, argued that aid should be withheld because India had not done enough to rein in their population size, saying, “I’m not going to piss away foreign aid in nations where they refuse to deal with their own population problems.”

Human nature being what it is, these incentives led to predictably dark places, especially in India. Dylan Matthews and Byrd Pinkerton summed it up well in their 2019 article, “ ‘The time of vasectomy’: how American foundations fueled a terrible atrocity in India”:

“In 1975, Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi ordered the declaration of a national emergency. She seized dictatorial powers, imprisoned her political rivals, and embarked, with the help of her son Sanjay, on a mass, compulsory sterilization program that registers as one of the most disturbing and vast human rights violations in the country’s modern history.” [Hyperlink added]

McNamara was apparently pleased. “At long last, India is moving to effectively address its population problem.” The “best and the brightest” never disappoint.

The population panic of the 1960s and 70s was grounded in dire predictions that stemmed from failed guesses about population growth, simplistic expectations that current trends will always hold, and foolish assumptions that new discoveries will not be made. In Limits to Growth, the authors estimated that by the year 2000, there would be 7 billion people, and more than 15 billion by 2030. In reality, there were 6.1 billion people at the turn of the millennium, and there are 8.1 billion now. Given how much further technology developed than the experts of yesteryear anticipated, even if there were 15 billion people today, we would not be facing famine-induced “great die-offs”, but rather Ozempic riots due to shortages.

How it’s Going

Things didn’t pan out how the overpopulation alarmists prognosticated. So much so, in fact, that today, the rising fear is that humanity is on track to dwindle away. The UN now estimates that, due to falling global birth rates, the human population is set to peak in 2086 at approximately 10.3 billion people before tapering off and then declining. Other estimates place this peak in the 2070s or 2060s. By the year 2100, the population is projected to already be in decline, falling to 10.18 billion, with the total fertility rate (TFR) estimated to be around 1.6 births per female (a TFR of 2.1 being replacement level). 97 percent of countries are expected to be below replacement level.

Extrapolating further out, a 2013 study in Demographic Research projected that with a steady TFR of 1.6, the human population would be around 2 billion by 2300. A 2023 analysis in the International Journal of Forecasting, whose model assumes various TFR fluctuation scenarios, projects a population of about 7.5 billion in 2300, with the low-end projection being 2.3 billion. These models can vary widely in their design, in part because of how many variables there are. As a result, depending on the assumed fertility rate, population estimates that stretch into the far future range wildly, from as low as 1 billion people in 2300 to as many as 36.4 billion.

Of course, one need not be a demographer or population scientist to read the news or headline stats and extrapolate that into a rough trend line. It is common knowledge at this point that people around the globe are having fewer kids, and in a growing number of countries, at well below replacement level. In places like South Korea, it’s gotten so bad that more than 150 schools across the country had no first graders in the 2023–24 school year. The South Korean fertility rate is expected to fall from 0.78 in 2022 to 0.65 in 2025. It doesn’t take a statistician to put two and two together and begin worrying about what this could mean for the future of humanity if continued unabated. After all, the trends that correlate with falling birth rates — including economic development, education, secularization, birth control, social security programs, and women’s rights — are only moving in one direction.

Over the past decade, progressives have sought to cast any concern over depopulation as an artifact of the far right or even an outright expression of white supremacy. And while it’s true that many on the far right are indeed fixated on declining birth rates of white people, the worldwide issue of falling birth rates is fast reaching escape velocity across the political spectrum. In a 2022 article titled “The End of Economic Growth? Unintended Consequences of a Declining Population”, the American Economic Association argues a shrinking population translates to stagnating economic growth. The Economist warns of “less growth and a more fractious world.” Business Insider foresees “economic chaos” and “looming disaster.”

The New York Times writes that “In a world with fewer people in it, the loss of so much human potential may threaten humanity’s continued path toward better lives,” and implores “It’s not too early to take depopulation seriously.” The author, Dean Spears, also worries that a population decline might precipitate a wave of ultraconservative religious extremism that uses the population crisis as a pretext to stage an authoritarian takeover of society and a drastic rollback of women’s rights — a real-life Handmaid’s Tale.

This all sounds properly alarming, but before you join the “pro-natalism” movement and start having kids by the dozen and naming them things like “X AE A-XII”, “Exa Dark Sideræl”, and “Techno Mechanicus”, let’s apply a little skepticism, perspective, and cold water.

Rumors of Humanity’s Demise are Greatly Exaggerated

Given how wrong the neo-Malthusians of the 1960s and 70s were about the “population bomb”, it’s worth scrutinizing how accurate our current projections, and their predicted downstream effects, really are.

By far the most reliable aspect of population predictions is the math involved. Trained scholars, informed by large data sets, using established statistical methods to extrapolate past and current trends into future, and then being reviewed and criticized by their peers, is a process no serious person disputes. But just because the math is correct does not make the prediction true. A logical argument can validly follow from its premise but still be unsound if the premise is inaccurate. And the premise baked into future population models cannot possibly account for all of the variables that contribute to population size, nor the countless unexpected twists and turns on which so much ends up hinging.

Nearly all predictions assume that life expectancy will continue to rise globally, but they are not equipped to know what kinds of innovations will occur in dozens of other areas relevant to population size. The overpopulation experts of the 20th century, for example, extrapolated the population data they had into the future while assuming mid-20th century technology. They could not foresee the many efficiency improvements in transportation, manufacturing, agriculture, communication, food science, and globalization that enabled a world where the overweight outnumber the hungry by more than four to one.

Around the world, we’ve seen that as women gain more rights, freedoms, and opportunities, they have fewer kids, in part because many opt to have children later in life, reducing their fertility window. The advent of women’s rights did not extinguish the female desire for motherhood. As per the 2020 US Census, 61.5 percent of women aged 30–34 have given birth to at least one child. Of the remainder who have no children, Pew Research found that 45 percent said that they want kids. Another study from 2013 found that among women aged 40–44, 42 percent of those who had never had children wanted to have one, and 20 percent of women who already had kids said they wanted more. These figures were 35 percent and 16 percent, respectively, in 2002. Women want children, but they want them, on average, later in life, when conception becomes difficult, expensive, and eventually impossible.

What happens if — or more likely, when — medical science solves this?

Are we really going to assume that by the year 2100, or 2300, women will still struggle to have children in their 40s, and be unable to give birth in their 50s? Are we going to assume that fertility drugs, treatments, procedures, and technologies will make no progress? That their funding and demand won’t massively increase over time, and that their costs won’t be eagerly subsidized by governments desperate for higher birth rates? Are we going to suppose that no new inventions come along, the likes of which we could no more envision today than Paul Ehrlich in 1968 could have imagined GMO crops that improve yields by 36 percent in developing countries?

Similarly, automation, artificial intelligence, and efficiency are only going to continue improving, reducing the amount of human labor required and freeing up more time that many people “too busy” to raise families could use to do just that. The role that pollution, contaminants, radiofrequency radiation, and microplastics play in harming fertility will only become better understood and then better regulated and mitigated. Never bet against the regulatory state becoming more sprawling and Byzantine. Governments, institutions, and cultural leaders will not sit idly on their hands while they preside over societies diminishing into nothingness. They will exert their influence to shift the incentives and change the culture around promoting more offspring.

But let’s suppose none of these things come to pass. Let’s suppose that by the mid 22nd century, humanity basically knows nothing more about fertility than we do right now, that our environment is just as poorly regulated, our leaders just as disengaged, and our technology either frozen in time or more deleterious. Any given generation, whether in an act of rebellion, revival, renaissance, or simple duty, can choose to reverse the current trends. And if they do, the most dire-seeming population decline can be stopped dead in its tracks in just a handful of years. According to a 2024 study authored by the aforementioned Dean Spears (and funded by Elon Musk), if the fertility rate were to continue dropping as projected but then rebound to replacement level in the year 2175, the population would stabilize at 6 billion people. Even the population collapse advocates’ own in-house research works against them.

This notion that Millennials or Gen Z having fewer kids will lastingly hamstring the human population relies on every subsequent generation continuing down the exact same road. But culture, society, laws, policies, and economics are always shifting. Things fall out of fashion and then come roaring back. Bell bottoms were a thing, and then they weren’t, and then they were again, and then they weren’t, and now they’re coming back once more, only a little different. So it may be, in 50 years, or 100 years, with having larger families. Trying to predict the endlessly complex subtleties and painfully fickle groupthink behind cultural trends goes beyond even the divining powers of Isaac Asimov’s fictional psychohistory. And the depopulation alarmists are no Hari Seldons.

Fewer People Isn’t the End of the World

All that said, the human population could very well begin a period of decline later this century. While some of the loudest voices bellow that falling birth rates “will lead to mass extinction of entire nations” to their 200 million followers, most people concerned about depopulation don’t actually think that humanity is going to DINK itself to death. A few express abstract philosophical objections about future happy people who might exist but never will. Others explicitly appeal to religion. For the most part, however, the folks sounding the alarm about a future population drop have more material concerns resting on the long-established link between population growth and economic growth. The more people there are in a society, the more labor, businesses, productivity, innovation, and consumers we can expect — and the fewer people there are, the fewer of these things. A dwindling human species, these critics therefore argue, would cause, at best, economic stagnation and a halt to progress, and at worst, a severe global depression and backslide of living standards that could potentially lead to a civilizational unraveling.

Here again, the transformative role of technology is undervalued. As machines subsume an increasing share of labor — manual, creative, and intellectual — it may be possible to mitigate the economic effects of fewer humans. A 2023 McKinsey report, for example, estimates that “Current generative AI and other technologies have the potential to automate work activities that absorb 60 to 70 percent of employees’ time today.” And that’s for “current” technologies, to speak nothing of the kind of tech that will likely exist in the future. Half of today’s work activities, they estimate, “could be automated between 2030 and 2060.” The authors calculate “AI’s potential impact on the global economy” to be 17.1–25.6 trillion dollars at present.

Will a future where humanity shrinks but technology flourishes be an economic net-positive, or at least a wash? It might, but we can’t say for sure, because forecasting the future is never sure. What we can be confident in is that technology will play a significant role in absorbing human labor, increasing productivity, and generating economic growth. We can say this because it’s happened throughout history. Given this, I have an exceedingly hard time imagining a depopulation-induced global economic collapse, and, as Han Solo once said, “I can imagine quite a bit.”

There is a reason why this iteration of population panic has always been most prevalent among people politically right-of-center, and especially among uber-capitalist business types, because both share the growth ideology. It’s a binary mindset in which there can be only two modes: growth and decay. Anything that is not growth, including a slight decline, or staying the same, or even growing but at too modest a pace, is, in this worldview, catastrophized as a ruinous disaster. This is the religion of every publicly traded company’s board of directors, the imperative of every major CEO, and the pervading culture of every sales force. It’s Alec Baldwin from Glengarry Glen Ross (1992). Always be closing. Coffee’s for closers. Didn’t hit your numbers this month? Hit the road, you worthless waste of space. These are the folks who think the human race ought to be managed like a Fortune 500 company operating under the immense pressures of shareholders and a board to exponentially grow forever and ever. Any hitch in glorious infinite growth, to this way of thinking, is an apocalyptic affront to the almighty invisible hand.

I bring this up not merely as a character attack, but because their arguments cannot be fully understood without the context of this broader worldview. As someone with a background in business, I saw this mindset firsthand for close to 15 years. It is diseased. Indeed, in medicine, there is a name for unchecked growth for growth’s sake: cancer. And that is, in large part, what humanity’s growth has been for the planet and the rest of its inhabitants. Man has wiped out 60 percent of vertebrate animals since 1970. 1 million species are on the brink of extinction as they vanish “at a rate not seen in 10 million years.” We have polluted the environment, disrupted the climate, cut down the rainforests, destroyed ecosystems, and even littered Earth orbit with 170 million pieces of “space junk.” Dirty air now accounts for between 8 and 10 million deaths per year. An analysis of a two-month period of China’s draconian pandemic lockdowns during 2020 revealed that tamping down industry for 60 days saved between 50,000 and 75,000 lives from reduced air pollution alone.

It’s worth taking a step back from our own self-centered considerations to ask whether fewer humans might be better for the planet. The answer is an unquestionable, resounding yes. But as is often the case, when we help others, we also help ourselves. Anyone who’s ever experienced rush hour on the 405, the Schuylkill expressway, or really anywhere in North Jersey or New York City might justifiably wonder why having a bit fewer people clogging things up would be so horrible. Anyone who has ever spent time in Tokyo, Hong Kong, or Mumbai understands what too much humanity looks like. But more profoundly, a decline in the human population can give us — and the environment — some much-needed breathing room. It can give us the time to evolve more ethical and enlightened cultural mores and to develop cleaner, more efficient, and less wasteful and damaging practices before we strip-mine and pollute our only home into an unlivable husk. No, a shrinking population isn’t the end of the world — in fact, it might just be what saves it.

***

The scientist J.B.S. Haldane mused in 1927 that “the universe is not only queerer than we suppose, but queerer than we can suppose.” We can add that the universe is also more complex than we can understand. This isn’t to say we can never know anything, or that modeling the future is pointless. What it means is that we would be prudent to temper our expectations and to treat the most grandiose and cataclysmic predictions with an extra dollop of skepticism.

At the end of the day, depopulation alarmists and skeptics alike are both sailing in the murky waters of speculation and guesswork. There are no crystal balls, however the past can be instructive, or, at the very least, can provide some useful perspective. In the span of two generations, experts went from fearing an Earth overrun by humans to holding symposiums about an “empty planet.” Can we truly say, with a straight face, that we know what the future holds? At what point do our bungled predictions and chronic inability to account for life’s countless moving parts force us to adopt some humility? There are a thousand calamities that might befall us in the coming decades or centuries that could end humanity as we know it. When it comes to the depopulation bomb, I’m not losing any sleep.

See also:

“When 65 is Young: The Politics of Life Extension”

“Transhumanism and Its Very Silly Critics”

“Freddie deBoer Is Wrong About Effective Altruism”

Subscribe now and never miss a new post. You can also support the work on Patreon. Please consider sharing this article on your social networks, and hit the like button so more people can discover it. You can reach me at @AmericnDreaming on Twitter, or at AmericanDreaming08@Gmail.com.

Great article!

I contend that moderns man’s greatest folly is presuming that what solves on a spreadsheet applies at scale.

Paul Ehrlich has become the whipping boy for every depopulation alarmist. His book THE POPULATION BOMB was a warning. Since then, we have been poisoned by micro-plastics, chemtrails, countless chemicals in our food, and tons of sugar.

How has mankind survived? A naturally occurring event - people stopped having babies through choice and/or through the contamination of our planet. Of course, war will eventually remove much of the world's best breeding stock and the elderly will require sophisticated robots to provide care until we die. (a great improvement over the underpaid and often disinterested aides that shuffle around in nursing homes).

A good primer for the 21st century would be Terry Gilliam's movie BRAZIL.