2021: My Compelling and Rich Year in Books

“There are two motives for reading a book; one, that you enjoy it; the other, that you can boast about it.” — Bertrand Russell

For nearly a decade, I’ve been setting myself yearly reading challenges on GoodReads. Some years I bite off more than I can chew and fall short. Other years I blow it away. This year I cheated by lowering the goal most of the way through when it was clear I wasn’t going to make it. I’ve simply been spending too much time writing! I ended up reading 35 books in 2021. This post will include brief reviews of 20 of them. You can see the full list here.

My Favorite Books Read in 2021

Nonfiction

“Disturber of the Peace: The Life of H.L. Mencken” (1950) by William Manchester

This biography of Mencken from his friend and protégé William Manchester, breathes life and three-dimensionality into the persona, work, and legacy of the legendary critic and writer. The layers, complexities, seeming contradictions, but fundamental consistency of how Mencken thought and lived are beautifully laid out, with the rigor of a skilled journalist and the insight of a close friend. “Disturber” did something no prior book ever had — it made me hesitant to read the last few pages because I didn’t want it to end.

“Out on a Limb: Selected Writing, 1989–2021” (2021) by Andrew Sullivan

Andrew Sullivan’s wonderfully written and well-curated collection of 60 essays is a thing of beauty. It’s just one fucking masterpiece after another. From his intensely personal pieces on homosexuality, the AIDS crisis, and Catholicism, to marriage equality, drugs, hate, culture wars, political analysis, authoritarianism, and partisan hypocrisies, Sullivan’s writing shows a clarity of thought, a commitment to principles, and the humility to admit fault that makes for such enjoyable and thoughtful prose.

“Woke Racism: How a New Religion Has Betrayed Black America” (2021) by John McWhorter

Short, sweet, and to the point, McWhorter’s “Woke Racism” hits every note on the convergence of politics, race, and culture in America, and does so with pitch-perfect clarity.

Fiction

“Being There” (1971) by Jerzy Kosiński

This little satire about an earnest simpleton who stumbles out of his sheltered existence and quickly finds himself numbered among the foremost intellectuals and influencers in society is simply perfection.

“Rhythm of War” (The Stormlight Archive, book four) (2020) by Brandon Sanderson

(Spoiler free) Sanderson’s epic fantasy novels in his flagship “Stormlight Archive” series are my favorite works of fiction — of any medium or genre. It’s not for everyone, but if you enjoy fantasy, start with book one, “The Way of Kings.” I cannot recommend it highly enough.

Rhythm of War had a different feel from its predecessors. Sanderson greatly accelerated the process of pulling back the curtain on the master arc of the series — the story behind the story. We learn more here about his fictional universe, the “Cosmere”, than in the first three novels combined. There was a particular thematic focus on the mental health of the characters, as they dealt with what we’d call depression, addiction, anxiety, and psychosis. The final few hundred pages were an emotional roller coaster with a number of huge twists and one series-shifting shock that will leave you reeling.

More Mencken

“Ventures Into Verse” (1903) by H.L. Mencken

Published in his young adulthood, long before his ascendance as a critic and commentator, Mencken spent years later in life buying up copies and suppressing his youthful foray into poetry in hopes that few would be able to get their hands on a copy. It feels almost voyeuristic to read a work so uncharacteristic of an author, and which they desperately wanted to erase out of embarrassment.

Poetry was not Mencken's calling, to say the least, but reading this was fascinating, nevertheless. Some of the poems read like assignments from a disinterested student. Others offered glimpses into some Menckenian attitudes and insights. Many were military or martial in theme. The final poem in the collection, "Finis", on death and impermanence, spoke most to me.

“In Defense of Women” (1918, 1922) by H.L. Mencken

When I first read “In Defense of Women” six years ago, I felt that despite Menken's always-enjoyable wit and style, this book felt more dated and decidedly less enlightened than much of his other writing. Now after a second reading, having learned more about history, Mencken, and life, I have a greater appreciation for the work, even if some of the views expressed in it are outmoded. Mencken was a cynic, a curmudgeon, an iconoclast, and a misanthrope. He hated the world and just about everyone in it. He pays women a series of backhanded compliments that would strike any modern reader as quite insulting, while absolutely eviscerating men at every turn, at one point describing the average man as a fellow of “Petty meanness and stupidity”, “Puling sentimentality and credulity” with the “Bombastic air of a cock on a dunghill”, and whose attempts to express affection “Suggests a gorilla’s efforts to play the violin.” “In Defense of Women” does not read as a typical “pro-woman” work, but to those familiar with Mencken, this was the closest thing to praise he was capable of.

Other Nonfiction Selections

“Futureproof: 9 Rules for Humans in the Age of Automation” (2021) by Kevin Roose

(Side note: I was interviewed for this book by New York Times tech writer Kevin Roose in 2019, based on a Twitter thread on automation I’d posted that he found interesting. I’m quoted in the book, which is neat.)

Futureproof offers a nuanced exploration of automation in a way that threads the needle between anti and pro-automation views and between techno-optimism and techno-pessimism. Roose's nine rules are thoughtful, sound advice. What detracted from this book were the unnecessary repeated woke invocations. You can only inject white privilege, race, and [insert Vox’s style guide] so many times in a book about technology before it becomes contrived and ridiculous. We get it, you’re one of the good ones, Kevin.

“The Case Against Education: Why the Education System Is a Waste of Time and Money” (2018) by Bryan Caplan

Caplan builds his case against education step-by-step. He establishes how little students learn and retain from formal education, how few marketable skills are gained, and how unenjoyable most students find the experience. He explores the debate between “human capital purism” (students are transformed by education) and “signaling” (education functions mostly as a credential for advancement). He arrives at a model claiming that the “education premium” (the benefits the educated enjoy over the less educated) is the result of roughly 80 percent signaling and 20 percent human capital.

Caplan concedes that in terms of individual self-interest, education generally tends to be lucrative, but a primarily signaling-driven phenomenon does not grow the pie, it merely redistributes it. Considering the enormous public and personal cost of education, and its mediocre societal return on investment, Caplan argues we would be better off with less education, reinvesting that money in other ways. His policy prescriptions are quite radical. His far-libertarian views run so contrary to popular opinion as to be jarring.

Most of us have been conditioned to view education as a pure good, even a panacea, and it’s worth reading a thoughtful counter argument. I’m not sure what I think of Caplan’s policy proposals, but he did give me something to think about — and that’s all I can really ask of any nonfiction book.

“The French Revolution: From Enlightenment to Tyranny” (2016) by Ian Davidson

An ideal book for anyone looking to learn about or refresh themselves on the French Revolution. It strikes the perfect balance for the curious lay reader: in-depth and substantive, but without being an exhaustive tome. An enjoyable read, large swaths of which were hard to put down.

“The Business Secrets of Drug Dealing” (2018) by Matt Taibbi

In this subversive how-to guide from the firsthand experience of a drug dealer who was never caught, Matt Taibbi’s anonymous collaborator, dubbed Huey Carmichael, lays out his code of precepts over the course of fascinating tales from his adventures. While sympathetic and likable, Huey occasionally reminds you that he is in fact a drug dealer, and the rudimentary code of honor he lives by is hardly the equivalent of real morality. Taibbi, a political writer, found Carmichael's political involvements too interesting not to include, but it felt out of place in a book about drug dealing. Nevertheless, a pure page-turner, this one.

“Forward: Notes on the Future of Our Democracy” (2021) by Andrew Yang

(This is an abbreviated excerpt from the longer treatment I gave this in a separate post)

Yang spends the chapters in his book, when he isn’t recounting his own journey, examining what’s broken in American politics. In one particularly illuminating chapter, he paints an elaborate picture of a citizen inspired to run for office to make a difference. The reader is taken along for the ride with this hypothetical candidate, from their decision to run, through their campaign and all the obstacles they face, through their early days in office, to what their day-to-day schedule realistically looks like. We see how they must navigate the internal hierarchies of Washington and party politics, how little power they actually have, how inordinate amounts of their time are consumed fundraising, how they’re surrounded by lobbyists and special interests offering them favors. We go through the lies they tell themselves as they get little done and scheme for their futures, and how the system ultimately burdens them with obligations, incentives, loyalties, and quid pro quos that change them over time. When they are finally in a position of real power, a decade or two after their odyssey begins, they are a different person.

“Let There Be Money: Understanding Modern Monetary Theory and Basic Income” (2021) by Scott Santens

Santens covers a great deal of territory in very few pages, exploring modern monetary theory (MMT), universal basic income, federal jobs guarantees, inflation, time, and work. MMT is the deepest realization of the abstract fictionality of money, and if embraced, causes a Matrix-like moment where the world appears as flowing code, the barriers in your mind fall away, and incredible things become possible. It also takes a deeper look at the underlying values and goals of the systems that run society, and the ways in which some of our economic applications have strayed from those goals. A banquet’s worth of food for thought packed into a book that can be read in a sitting or two.

“On Having No Head: Zen and the Rediscovery of the Obvious” (1961) by Douglas E. Harding

A brief treatise exploring the illusion of the self and the Zen concept of emptiness from a totally novel angle — using sensory perceptions in their most literal forms to provoke insights about the nature of existence.

“On Revolution” (1956) by Hannah Arendt

Arendt narrowly focuses on the American and French Revolutions, endlessly analyzing and comparing/contrasting them with a tediousness that soon exhausts the interest of any casual reader. Getting through this was like watching someone assemble one of those tiny ships in a bottle, working for hours teasing the pieces into place with tweezers. Arendt is held in such reverence by so many thinkers and writers I admire, I suppose I assumed she must have been a more gifted writer. I know how that sounds, but this was a textbook, and it didn’t have to be. Some genuinely interesting insights, but disappointing.

“Facing Reality: Two Truths about Race in America” (2021) by Charles Murray

Murray lays out the data on differences in IQ and standardized test scores as well as criminality between the various racial populations in society. While there is virtually nothing in this book that is factually inaccurate (as of time of writing), this issue is complex and multifactorial, and certain aspects of the existing data are not as robust as they should be. Anyone looking to dismiss Murray’s thesis can take refuge in that.

The fact that Murray’s reputation comes with a lot of baggage, plus the fact that this sort of data so bluntly stated is guaranteed to delight some of society’s most odious people, will present too big an obstacle for most people left-of-center to give it a fair hearing. That’s understandable, and Murray is not the right messenger to convince anyone. If we want to improve the world, however, we should begin from the most accurate factual foundation. While this short book may be an uncomfortable read, believe it or not, Klan robes will not materialize on your person while doing so.

“Irreversible Damage: The Transgender Craze Seducing Our Daughters” (2020) Abigail Shrier

An explosively controversial book in today’s climate, “Irreversible Damage” does little to soften its blows. Written from an obviously conservative perspective, Shrier examines the recent surge in female-to-male transition among girls and young women. While she states a general acceptance of trans, she attributes this sharp rise among younger females to a combination of social influence, culture, parenting, politics, technology, and the way adolescent feminine insecurities intersect with these.

The meat of the book is a series of stories reported personally by Shrier. The stories are compelling, in some cases heartbreaking. At bottom, they are anecdotes, however. The ratio of data to stories was simply too lopsided toward the latter. Shrier also includes a chapter chronicling all the grizzly mishaps that chemical or surgical transition can wreak on the body, reminiscent of anti-drug and anti-STD campaigns of the 80s and 90s. The book is, from its title to the last page, a culturally conservative polemic. That in itself doesn't mean Shrier is wrong, but it means this is a very one-sided and incomplete analysis.

Shrier is not writing this to convince the left half of society, much less trans activists. The target audience here are the same kinds of normies who regularly watch their local evening news. And, indeed, just like those local newscasts, this book will scare the ever-loving shit out of them. That, perhaps, is my biggest issue. There is reason to suspect an element of social contagion in this phenomenon among adolescent females, and that it’s something to keep an eye on and study more. But it seems overblown and irresponsible to take as alarmist an angle as I think this book does.

Other Fiction Selections

“It” (1986) by Stephen King

You know that feeling when you finish a book you really loved, and you wished it would have gone on forever? “It” is what happens when that book actually does go on forever. A spellbinding, masterfully told story with an excellent cast of characters, but its gargantuan length almost burns you out, and by the time the epic finale comes, a part of you just wants to get it over with.

“Jeeves and the King of Clubs” (2018) by Ben Schott

A remarkable homage to P.G. Wodehouse’s Jeeves and Wooster series that hits every Wodehousian note so well you forget it’s not the man himself writing. Such a fun, humorous novel.

“A Tale of Two Cities” (1859) by Charles Dickens

Reading this classic work of French Revolution era historical fiction was something of a chore at first. I was determined to slog through it the rest of the way when, just over halfway through, the story blessedly began to gain steam. The drama and conflict built, culminating in an emotionally powerful ending that almost — but not quite — made up for the dull and meandering first half.

See also: “The Liberal Arts Crash Course”

Subscribe now and never miss a new post. You can also support the work on Patreon. Please consider sharing this on your social networks. You can reach me at @AmericnDreaming on Twitter, or at AmericanDreaming08@Gmail.com.

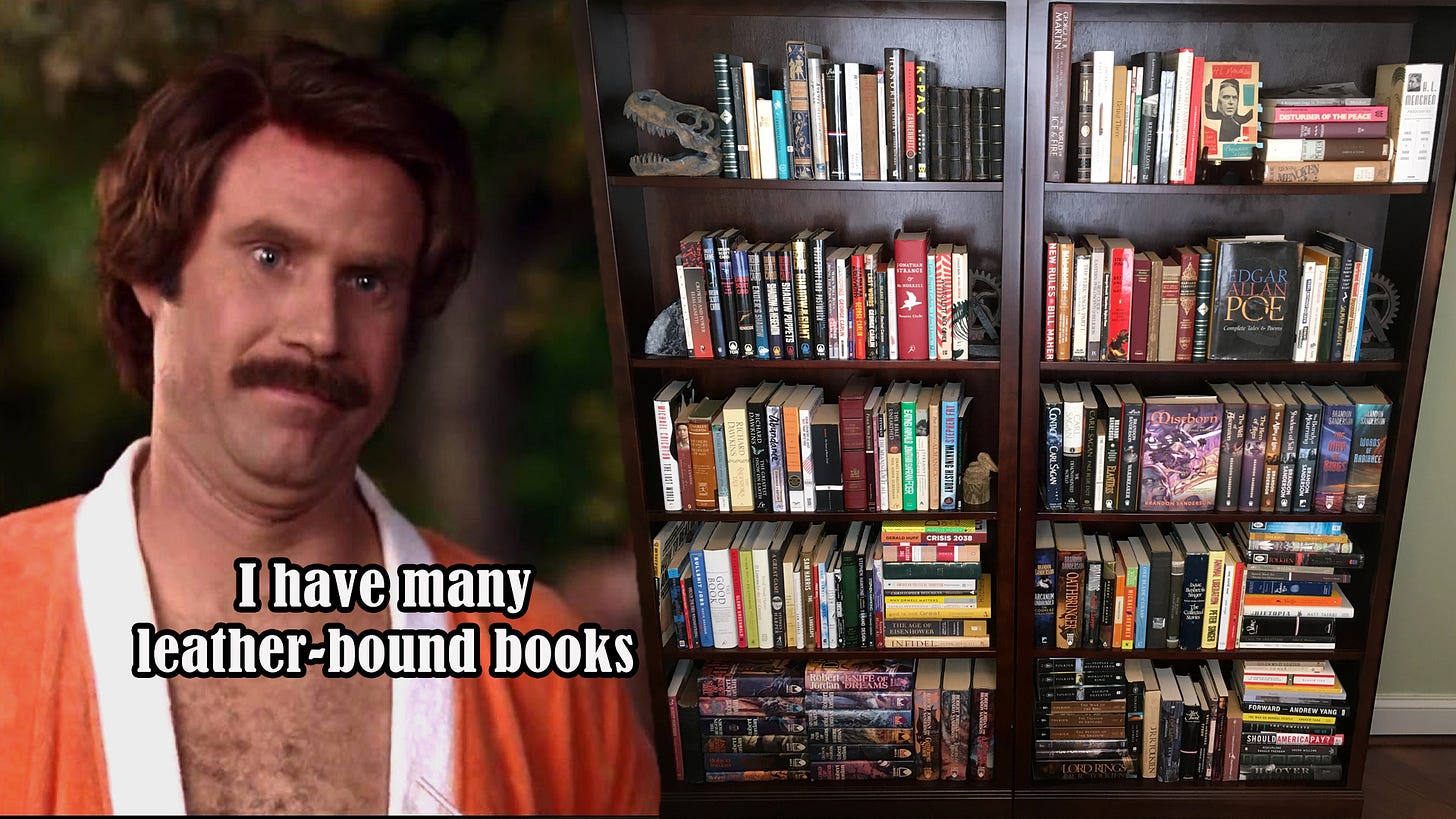

I came for the review of Irreversible Damage linked in your more recent piece deconstructing the "social contagion" hypothesis, stayed to zoom on your bookshelf which looks like a copy/paste of one of mine (minus the Robert Jordan, had to draw the line there).

Now I'm studying your collection like Patrick Bateman. "Oh my God, Is that a 1st edition of Jurassic Park?"