Journalism Should Be More Than a Rich Kids’ Hobby

There will never be a “diversity of thought” until there is a diversity of class.

According to Gallup polls, only 53 percent of the US has “some” or more confidence in newspapers, down from 75 percent in 2000. For television news, it’s 46 percent, down from 76 percent in 2000. Year by year, public trust is crumbling away. If current trends persist, we will reach a state by the end of this decade where substantial majorities have little to no trust in the national news media, and where those who do overwhelmingly only partially trust them (the latter is already the case). There are many reasons for this decline, some of which I’ve written about at length. One area that deserves a longer individual treatment is the lack of diversity in journalism, and in the intelligentsia more generally. In particular, socioeconomic diversity: the diversity of class.

While diversity is all the rage in elite and institutional circles these days, it mostly rings hollow because it’s seldom more than skin-deep. Tour the halls that guide and curate the national conversation, and you will see every race, faith, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, and identity group. And where you don’t, unless it’s a rare right-wing enclave (and often even if it is), you can bet that management is desperately looking to check off more diversity boxes. Every color of the rainbow — and many in between — are dutifully represented, all singing the exact same song in pitch-perfect hive-minded unison. As I’ve previously noted, “There is a stunning homogeneity of thought — one that is consistently out of step with the lives of the average citizen, and which often doesn’t represent their best interests.”

Like many critics of wokeness, I have made frequent reference to the “diversity of thought.” Many of our elite institutions, we recite as though a mantra, “have every kind of diversity except the one that matters most: the diversity of thought.” I realize now that this is untrue on both levels, and an imprecise lens through which to assess the problem. It’s not the only kind of diversity lacking, nor is it the most important. Not every issue is a question of morals, personal values, or subjective interpretation, where a variety of differing perspectives enriches the conversation. Any editor-in-chief seeking to secure a flat-Earther, 9-11 truther, anti-vaxxer, Jihadist, young earth creationist, or QAnoner on their payrolls to provide a diversity of thought should have their brains studied by science, and probably scanned for tumors.

Even on more justifiable issues, a truly representative diversity of thought will inevitably entail some form of political affirmative action, where right-leaning prospects would be given preference and lowered standards in hiring, given that every journalistic applicant pool will skew left-of-center. While it would be amusing to watch self-identified conservatives happily accept and cheer such developments, and thereby make hypocrites of themselves for the trillionth time, group quotas and diversity hires are ham-fisted shortcuts that don’t address root causes, and should be opposed on principle. Socioeconomic diversity is more scarce than thought-diversity in newsrooms, and, indeed, the latter flows from the former. There can be no diversity of thought until we first establish a diversity of class.

As journalist Batya Ungar-Sargon has written in her media criticism book Bad News (2021), journalism used to be a blue-collar trade:

“In the 1930s, just three in ten journalists had finished college. In 1960, it was two-thirds; a third of reporters and editors still hadn’t been to college, even just for a year or two. By 1983, the number of American journalists who had completed college jumped to 75 percent. By 1992, it was 82 percent of all journalists; by 2002, it was 89 percent; and by 2015, just 8 percent of all journalists hadn’t been to college, a number that is certainly even smaller today.”

Today, national journalists are overwhelmingly educated, often from the top universities, and with postgraduate degrees. Members of the press also enjoy immense influence and social standing. The Watergate scandal of the Nixon years inspired a generation of young reporters with a new model of the journalist as socialite, minor celebrity, thinkfluencer, and kingmaker (or kingslayer). In the years since, writers, editors, and commentators have joined our version of the Brahmin caste, and social media has only put this on steroids. Fast-tracked into “verified” check-marked status on nearly every social media platform, journalists, who, like society more generally, increasingly live online, now have a visual marker to go along with the figurative one that distinguishes them from the rabble. Even as trust in the news media reenacts Jules Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth (1867) by plunging to hitherto unexplored depths, all parties are aware that when a journalist speaks, their words are meant to carry a gravitas that a factory foreman’s, accountant’s, or small business owner’s are not.

Paradoxically, journalism, on the whole, is not a very well-paying profession. Sure, one can become quite wealthy in the uppermost echelon, but the average annual salary for a journalist in the US is just over $42,000 a year, a sum rendered all the more modest considering that most press jobs are concentrated in a handful a big cities, a dynamic that further supercharges the social stratification of the industry. At first glance, such salaries would seem to contradict the thesis being advanced here. Certainly, this is the foremost counterpoint that any defensive member of the media points to amid accusations of elitism or being out of touch.

This is a sneaky little sleight of hand. Here’s why it’s deceptive: Any industry that requires elite education and offers mediocre pay in return for vast influence and prestige will primarily attract trust fund kids, who can then turn around and claim to be “of the people” because they make 40 grand. But if you make 40-some thousand dollars, but have seven figures in a trust, or are heir to a fortune, or simply have considerable family assets to draw from or fall back on, then you are, in fact, part of the upper crust, and it’s (characteristically) disingenuous to pretend otherwise. Who but the leisure class could afford a $200,000 education and years of (virtually) unpaid internships, and then be able to move to one of the most expensive locations in the country for a paycheck comparable to a landscaper or garbage man? A low-pay high-prestige job will be sought by those who desire the prestige and do not need the money.

Just in my own news consumption habits, I’ve noticed that easily seven articles out of 10 are written by someone who is a PhD, professor, researcher, doctor, lawyer, or grad student — and are usually the son or daughter of one of the aforementioned. The range of thought one sees reflects the niche sensibilities of a certain social class even more than it does a particular political ideology. It’s another reason why a narrow focus on the diversity of thought misses the mark, because a center-right Georgetown professor and a center-left Georgetown professor do not constitute any sort of balance representative of the larger society.

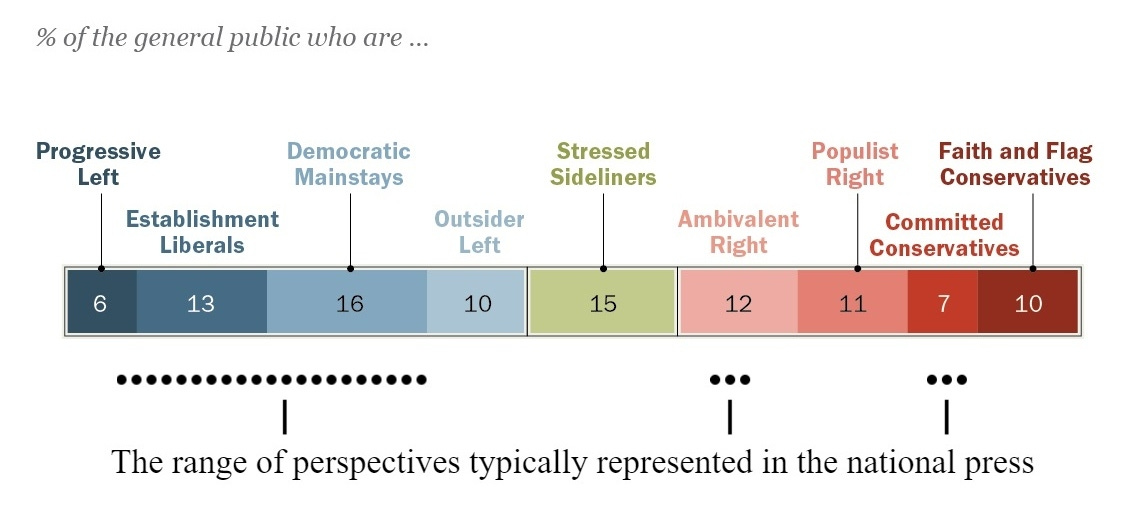

Staffing a publication with the likes of Michelle Goldberg on one side and David Brooks on the other allows you to say, on paper, that you publish perspectives on both sides of the aisle. In reality, such perspectives walk the gamut (there’s not enough to run) from woke #resistance Democrats to squishy Mitt Romney-style anti-Trump conservatives, excluding enormous swaths of the public, such as populists, libertarians, Marxists, Trumpists, the politically disillusioned, third-party voters, and heterodox liberals. You may not like some of those perspectives. Neither does the mainstream press. But taken together, they make up a majority of the country, whether you want to admit it or not. And if you cut them out of the Overton window, you can’t then be surprised when they tell you to take a long walk on a short pier.

The reason why journalists come off as so astoundingly out of touch with society, or why they fundamentally don’t understand Trump voters, isn’t because of politics. Talk to any working-class high school grad Democrat about why many folks in their neighborhoods and communities voted for Trump, and they’ll make a thousand times more sense than their more articulate and well-bred horn-rimmed bespectacled brethren from the New York Times or Washington Post. Why? Not because of any major political difference, though their politics likely do differ in some meaningful respects, but because they actually know these people. They live with and among them, work with them, and are friends with them. They are not a distillation of voting records and imprecisely-worded interview quotes. They are whole people.

One cannot be an effective public intellectual or commentator if they do not have a diverse socioeconomic peer group. It is as indispensable for understanding society as being educated and well-read. Having real human connections and relationships that cover a wide range of socioeconomic, educational, and geographic terrain is every bit as important as a solid foundation in history, politics, government, science, social science, philosophy, and the humanities. No amount of book learning or formal instruction can replace it. You won’t learn it from interviewing someone, or tagging along with them on an assignment. You have to live it, to a certain extent. For a crowd that so venerates “lived experience”, as with diversity, they consistently miss the most important lessons.

This is not to discount the role of education. I’ve met, known, and worked with many Joe or Jane six-packs who regarded their hands-on skills, trade experience, and street smarts with much the same arrogance that elites place on their advanced degrees and influential status. I’ve met many guys old enough to be my father who couldn't name the three branches of government, who know less about history than most 10-year-olds, and who have not read a book in their entire adult lives, but who nevertheless hold the unshakable conviction that they’ve got it all figured out. In their minds, decades spent hanging drywall or remodeling bathrooms has imbued them with all the wisdom life has to offer, and anything they happen not to know, well, that’s just obscure trivia knowledge that ain’t worth knowing. There will be no populist exaltation of the common man’s wisdom here. Not on my watch. Such imbecilities are as blinkered and preachy as any elitist screed. Know-it-all-ism transcends class boundaries, it’s just that the insufferabilities of the working-class variety torment a smaller radius of victims.

It may be unrealistic to expect journalism to return to being a blue-collar trade. Time was, only a tiny percentage of the country went to college, and without non-college educated journalists, there simply wouldn’t be enough people to fill the needed positions. Today, nearly 38 percent of adults have a four-year degree, and another 25 percent have some college experience or a two-year degree. While anyone can learn the requisite skills necessary to be a good writer, editor, reporter, or thinker without attending a institution of higher learning, most tend not to, and unless one has managed to “make it” on their own, it remains reasonable for news media organizations to discount applicants who can boast neither of college degrees nor relevant work experience or accomplishments. A 25-year-old who has never been published, has never worked in journalism or related fields, and has never attended college will remain a less desirable applicant than a 25-year-old with a college degree, or a 25-year-old who has never attended college, but has achieved success in the field independently.

If the press is to be made more socioeconomically diverse, it will not primarily be on the educational axis. That ship has sailed. In lieu of trying to roll back the clocks to some bygone age, the media should instead focus on diversifying the peer groups of existing journalists, and broadening the appeal of journalism to a wider range of socioeconomic backgrounds.

To address the first, we should geographically decentralize the media. As I’ve previously written:

“Most people who work in journalism and related fields are to be found in a handful of large coastal metro areas such as New York City, Boston, Washington D.C., Atlanta, Los Angeles, and the San Francisco Bay Area, with Chicago as one of the few major hubs on the interior. The media hasn't arbitrarily chosen these locations; this is also where the economic, industrial, intellectual, and political power is concentrated. One problem with this arrangement, aside from the drain on the rest of the country, is that these coastal power hubs foster a different kind of political and social ecosystem than the nation at large. … This leaves many almost completely disconnected from the day-to-day lived experience of most citizens… From within these bubbles, the press then proceeds to analyze, commentate, and report on a society they do not (or no longer) understand, and whose welfare they increasingly have less of a stake in.”

Modern technology allows people to be remotely connected in unprecedented ways. There is no need for journalists to be concentrated in a half dozen cities. Redistributing the press around the country would relocate a significant percentage to new places where they would meet, interact with, and be immersed in communities that they would otherwise have very little contact with. This would also have the side benefit of reinvigorating local and regional journalism, which has been vanishing at an alarming pace over the past several decades.

To broaden the appeal of journalism, the profession must be more highly paid. Not having to move to a large city will lower the price of entry in itself, and paying journalists more will attract a larger pool of talent from a wider cross section of socioeconomic backgrounds. As long as most positions are only modestly paid, only those who don’t need to worry about money will fill them. I’ve been very critical in the past of the profit motive’s role in degrading the quality of media coverage. I’m not sure I stand by that view as heartily as I used to. The fact is, most of the problems we see in for-profit media still exist in not-for-profit journalism, the most glaring example being NPR, which has in recent years gone so far beyond the parody of woke madness that no satirist, living or dead, could outdo it. I’ve come to appreciate that, as in most domains of life, you get what you pay for.

Journalists are increasingly aware of the ongoing nosedive in public trust. Whether the industry will wake up and change course is a question on which the future may depend. Trust is the glue that binds society, and information is the fuel that powers it. Should the day come where trust — and trust in information — hits rock bottom, anything becomes possible. Like a society without an immune system, we will be left vulnerable to the first pathogen, however ordinarily resistible, to cross our paths. We need a new generation of trailblazers and trendsetters willing to innovate, to be unpopular with their elite peers, and to see beyond their own immediate selfish incentives to the longer view. These are not common traits, to say the least, but, as the anthropologist Margaret Mead once observed, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.”

See also: “Nobody Wins in the Information Wars”

Subscribe now and never miss a new post. You can also support the work on Patreon. Please consider sharing this on your social networks. You can reach me at @AmericnDreaming on Twitter, or at AmericanDreaming08@Gmail.com.

Journalism is neither a profession nor a craft. There are no entry criteria, credentials, training, testing, or certifications required. As a former DC denizen, journalists are as a whole not respected or feted. A named few perhaps, but they are also vilified. Costa of CNN comes to mind. Overall they get no respect. Some make a big deal about getting a Pulitzer Prize, but then again, so did Westbrook Pegler.

Today anyone can be media or a journalist. Nobody issues press credentials except the White House. You are a journalist is you call yourself one and enjoy all the same protections as a reporter for WaPo, CNN. or Fox. First Amendment auditors, website operators, and blog writers are all considered journalists.

To think they journalists are just in a few major cities is both hubris and and ignorant.

As such they are already distributed through out the nation, in all counties and townships.