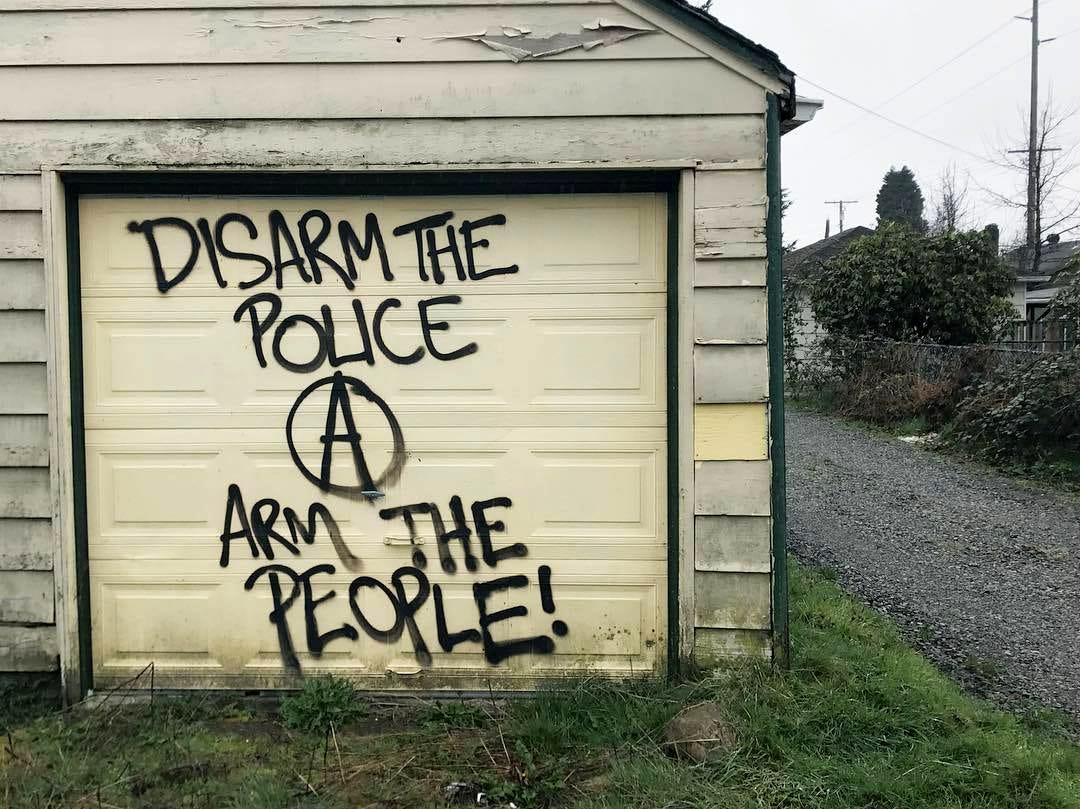

Okay, We’ve Dismantled the State. Now What?

Anarchism is heavy on criticism of the status quo, but light on realistic solutions.

I have a new piece out in Queer Majority: “The Culture Wars Come For Sex Research”

Anarchists aren’t exactly a political force to be reckoned with. The level of direct power they wield is somewhere in between the knitting lobby and Big Broccoli. But while anarchists remain a fringe, many of their ideas are shared by broader segments within both the political left and right, who, in their own ways, harbor deep, sometimes radical skepticism of authority. Right- and left-libertarians are not necessarily anarchists, but anarchism represents anti-authority attitudes taken to their logical conclusion. Like so many extreme ideologies, anarchism begins with valid critiques of the current system. The US, for example, isn’t as democratically responsive and representative as it could be. We don’t always like how our tax dollars are spent. We don’t always agree with the laws or foreign policy. The war on drugs is bad. There isn’t as much socio-economic mobility as we would like. Where things go off the rails, however, is when the discussion turns to solutions. Anarchist thought is heavy on criticism of the establishment and the status quo, but light on realistic alternatives. The simple question our would-be destroyers of the state cannot coherently answer is: What comes next?

According to the New Oxford American Dictionary, anarchism is “A political theory advocating the abolition of hierarchical government and the organization of society on a voluntary, cooperative basis without recourse to force or compulsion.” Though neither recognizes the other’s legitimacy, there are both left and right-wing versions of this thinking. Anarchists on the left go by names like anarcho-communist, anarcho-socialist, libertarian-socialist, and anarcho-syndicalist. They envision a form of socialism, but without the state. They advocate for the abolition of police, prisons, markets, and every form of hierarchy. Across the aisle are folks too radical to be described merely as libertarians and who get their own hyphenated name: anarcho-capitalists, or ancaps for short. Ancaps too pine for the eradication of the state, not so that socialism can flourish, but so that unbridled individualism and market forces can govern everything. They dream of a country free from taxation, regulation, and statute laws.

To advocate for such a radical reorganization of society would seem to necessitate some sort of practically actionable plan. But anarchism has no answers. Asked to provide some specifics, Noam Chomsky, the most prominent contemporary anarchist, said, “So what would an anarchist society look like? [...] Steps toward more freedom or the elimination of illegitimate structures of authority, and where it goes is for people to make their own decisions about.”

How do we deal with nuclear reactors, which require constant maintenance and upkeep to avoid disaster, and rely on a complex supply chain to function? On the wider issue of infrastructure, how could a localized, communal model replace the supply chains necessary for everything we need to function? In today’s globalized economy, it is more practical to build things using pre-made individual parts rather than make them all in-house. How could localized production, objectively less efficient, satisfy the needs of billions of people? What would the implications be for public health, wildlife, and the environment if all regulations were removed? How, in the absence of police, prisons, and the justice system, can society deal with rapists, thieves, con artists, murderers, and violence? What happens if a neighboring country, one that isn’t anarchist and doesn’t adhere to the non-aggression principle, declares war or invades?

It is perhaps uncharitable to say that anarchists have no answers — often they simply have non-answers. Many of them hinge on whataboutisms about their favorite bugbears: capitalism or the state, depending. Questions such as “How would we maintain basic order in the absence of a state?” prompt denunciations about how state authority is sometimes abused, or how disorder under the status quo does still occur now and then. How do we fund innovation that isn’t always immediately profitable without a state and taxes? Look over here, the government can be wasteful! How do we incentivize people to do unattractive jobs without the profit motive? Look over there at some evil perpetrated by capitalism! The gist is that because the current system is flawed, it’s therefore so irredeemable that anything else would be an improvement, as though we’re sitting at civilizational rock bottom where we have nowhere to go but up — a zygotic understanding of human history.

In other cases, it’s not that anarchists have no answers or non-answers, but very bad answers. Crime, we are told, will mostly just disappear in the absence of unjust laws and poverty. Not only does this assume that an anarchist society would effectively eradicate poverty, but the “poverty causes all crime” hypothesis doesn’t account for those sinister white-collar corporate criminals left-anarchists are always going on about. There are no Jean Valjeans on Wall Street, gambling away the retirement funds of working people to buy a loaf of bread to feed their family. Nor does it account for the most pathological antisocial behaviors. Violent psychopaths, serial killers, madmen, and sexual predators aren’t generally driven to commit their crimes out of disaffection with capitalism or the state. Any serious attempt by anarcho-lefties to address what to do about these ills results in reinventing the police and prisons but with extra steps and different names.

Citizens, we are assured, will want to labor for the communes, voluntarily performing necessary but menial and uninspiring tasks for no money. Why? Because humans desire to be useful, productive, and helpful, of course! Everything from work to trade to defense will be governed by contracts. Lots and lots of contracts. And what happens to people who cannot agree to any contracts? What happens to those unrepentant capitalists who refuse to get on board with the anarchist project? Fear not, comrades; anarchists won’t send them to any nasty old gulags. They’ll instead be sequestered at reform centers where the non-state will non-re-educate them to see the light. With freedom like this, who needs tyranny?

An observant reader will have noticed that most of the discussion so far has focused on left-anarchists, not anarcho-capitalists. That’s because many ancaps don’t even pretend to care about the logistics of how anarcho-capitalism would work in practice. As unabashedly radical individualists, their primary concern is about their own freedom to do whatever they want, however they want, without the government regulating, restricting, or taxing them. What effect would that have on the wider community? Hey what do we look like, a bunch of collectivists over here? “I got mine, you can go fuck off” doesn’t have quite the rhetorical flair of “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs”, but it is at least honest.

As has been noted in a previous piece, “The Goth Kids of Politics”, both left- and right-anarchist thinking relies upon a rather fanciful faith in humanity’s goodness and rationality. Anarcho-lefties must believe that people are naturally fair-minded and self-sacrificing for an functional anarchist society to seem imaginable, and ancaps must believe that individuals are utility-maximizing rationalists. The reality, of course, is that people are neither. We can be self-sacrificing, but usually only for those closest to us. We aspire to fair-mindedness, but are riddled with biases, prejudice, and blind spots. We are capable of rationality, but are derailed by impulsiveness, strong emotions, and delusion. Effective systems are those that help people become better versions of themselves. They enable prosocial behavior by incentivizing it. Virtue, in a well-thought-out system, is a byproduct — you feed selfishness in, you get virtue out. It’s not a good sign when a system requires high levels of individual virtue as an up-front energy source to fuel it.

Perhaps an even more insurmountable issue with an anarchist society is that it would require absolute conformity. This presents a fundamental problem. Anarchism rejects any form of authority the anarchist has not consented to. It takes the liberal principle of “consent of the governed” to an illiberal extreme where the consent of each and every individual becomes inviolable. The only way to avoid the paradox of forcing people to conform to non-authority and compelling them to be “free” is if every single person agrees with the baseline of anarchist thought. This runs contrary to human nature. Anarchism requires people to be opposed to authority and hierarchy when virtually every society ever produced, from hunter-gatherer tribes to complex civilizations have all incorporated some form of hierarchy and authority. And anarchism, for all of its pretensions of radical equality, would do the same.

Societies without laws are possible. The early settler Puritans come to mind, as theirs was a community governed by religious norms rather than secular law — one defined by strict and harsh social penalties for deviating from the norm. And that is the kind of society the anarchist would have to build to keep cohesion; one that imposes the values of anarchism with ruthless social force.

Left to their own devices, humans will splinter. It took about five minutes for Christianity to begin splitting into sects, each calling the others heretics and fighting bloody wars over millennia. No community can function if every one of its members must affirmatively consent to everything. No idea ever conceived has commanded 100 percent unanimous voluntary agreement. Anarchism is hardly the lone exception to this rule. Anarchists themselves are the poster children for humanity’s penchant for the narcissism of small differences. These people cannot even manage to run coffee shops and ranches with a handful of their comrades without spectacular implosions and meltdowns. The notion that they could ever run a society is the absolute zenith of absurdity.

***

It is easy to criticize. It is easy to be outraged at police brutality, the exploitation of workers, corruption in business and government, and the abuse of state authority. It’s easy to talk yourself into feeling like the whole system is rotten. And it’s easy to burn it all down. The structures, norms, values, and institutions that took centuries to cultivate could all be demolished in a series of months or even weeks, if it came down to it. Destroying is easy — it’s building that’s hard. It’s hard to appreciate the many things the system does right. It’s hard to recognize that for every justifiable complaint about the system, it quietly handles a dozen problems humans have struggled with up until only recently.

This “burn it all down” attitude betrays a great amount of privilege and historical ignorance. After the fall of Rome and the millennium of regressive, authoritarian rule that defined Europe, the Enlightenment sparked a questioning of the status quo — eventually leading not only to the American and French Revolutions, but an age of revolutions. Across the world, from Haiti to South America, to France, Germany, Italy, and Austria, the 1700–1800s saw people fighting tooth and nail for even a sliver of political rights in a world unimaginably brutal by modern standards. What emerged out of that strife was economically-mixed liberal democracy. Our forebears built a better world. A self-improving world. They built the civilization and ideals that have enabled anarchism to exist.

Anarchists of any stripe must reckon with the fact that it is the state that acts as the guarantor and protector of human, political, and civil rights. Our rights do not exist independent of us; they exist as laws, norms, and social constructs developed over centuries. Without the firm structure of a state to enforce our rights; without a guarantor to underwrite them, they might as well not exist. Without hierarchies and governments, the only way to secure rights would be force — but now without the accountability or checks and balances of liberal government. As usual, the desired state of anarchism would require reinventing the wheel, just less efficiently.

One of the first philosophers to call themselves an anarchist was Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, and its two most defining advocates were Mikhail Bakunin, the anarchist counterpart to Marx, and Peter Kropotkin. Proudhon was born in 1809 and grew up in the post-Napoleonic era of absolutist monarchy and hard-right authoritarianism, and Bakunin and Kropotkin grew up in Tsarist Russia. Under such repressive systems, with secret police and church and state combining to put their boot on the neck of the common man, it makes sense to want to reject the state entirely.

But since then, things have improved considerably. The problems highlighted by the originators of anarchism have since been addressed; the average citizen of an industrialized country has never had greater freedom, liberty, security, opportunity, and abundance. Anarchism is a 19th-century idea aimed at 19th-century problems. The anarchist rages against a machine that no longer exists. But there is a reason anarchism has lingered on, and it’s not all born of the knee-jerk teenage need to rebel and be different.

“I know quite a few anarchists, and while they aren’t all the same, the children of doctors and lawyers are definitely overrepresented.” — Katie Herzog

The allure of anarchism on the left is simple. As with socialists more broadly, anarchists tend to be young, white, and middle- or upper-middle class. These are people who, more often than not, have zero familiarity with hard living; people for whom righteous violence and struggle in service of a glorious cause are romanticized role-playing games rather than practical necessities against truly oppressive governments. Anarcho-imbecilism is just another ideological fashion accessory in their radical aesthetic. Most conveniently, anarchism also presents people with socialist tendencies the opportunity to sidestep having to explain, defend, or answer for the failures of communism by asserting that they didn’t do real socialism.

Anarcho-capitalism, for its part, appeals to those with pathological problems with all authority, and who desire to see their abject egocentrism validated. The poor are starving? That’s their responsibility. It’s not your fault they have it bad, and you should not be coerced into helping them! Like left-anarchists, most ancaps are financially comfortable, but unlike their counterparts, their status as one of the haves doesn’t lead them to harebrained notions of total equality, but rather to seek moral justification for why they owe nothing to society. It is the market-worshiping belief in the virtue of greed and selfishness elevated to religion. Like any radical ideology, the fanaticism with which it is believed is directly proportional to how unrealistic it is.

None of this is to say that we should blindly accept society as it is, or avoid questioning authority. On the contrary, any healthy democracy must maintain a reasonable skepticism of power at all times. Power invites corruption; it is an inherent flaw of human psychology that some will abuse their authority if given the chance. Nor is this to say that anarchists have not meaningfully contributed to political thought. Bryan Caplan’s The Case Against Education (2018) and David Graeber’s Bullshit Jobs (2018) are recent examples from both ends of the anarchist spectrum.

Authority does present problems. But there are better answers. Liberal democracy proved impressively resilient in the face of President Trump’s many authoritarian tendencies. The division of powers, rule of law, and liberal institutions prevented Trump from becoming an authoritarian strongman. That’s the crux of it — we have a system that works. It’s not without its flaws, to be sure, and robust criticism is both necessary and beneficial. But having some valid criticisms of the status quo isn’t enough to justify radical ideologies. You need well-thought-out alternatives that are logistically feasible, pragmatic, logically coherent, and which align with human nature. If you can’t cobble that together, you have to grow up and admit that boring old reform — the thing that has made your life a million times better than 99 percent of all the humans who’ve ever lived — will have to suffice. The horror.

See also: “The Goth Kids of Politics”

Subscribe now and never miss a new post. You can also support the work on Patreon. Please consider sharing this article on your social networks, and hit the like button so more people can discover it. You can reach me at @AmericnDreaming on Twitter, or at AmericanDreaming08@Gmail.com.