I often find myself, in day-to-day life, animated by feelings of intense dislike or even hatred. Hate is an emotion that comes so easily; unbidden, kindled at a moment's notice. It takes no effort at all — the feeling does all the work, the only thing you have to do is be a willing passenger to it. It could be brought on by the news, social media, a personal interaction with someone, or something even more trivial. In cases where there is an actual conflict, or a perceived wrong, hatred can intensify exponentially. It is a constant battle.

Hatred, it should be noted, is not quite the same as “hate” — as in “hate crime”, “hate speech”, or “no place for hate.” I’m not talking about bigotry, or culturally right wing views. I mean personal hatred — as in deeming someone an irredeemable piece of shit, wishing ill of them, cheering (if only inwardly) when misfortune befalls them, or even taking some action to cause them harm yourself. Hatred and “hate” can overlap, but they need not necessarily. Rivalry, conflict, disagreement, moral judgement, injustice, or perceived wrongdoing can inspire hatred as well as anything.

Hatred is, of course, unproductive. We’re cognizant of this in that platitudinous way we know we’re supposed to be, but we haven’t truly internalized it. There are those few whose fortuitous personalities seem to diminish their capacity for this emotion. The rest of us are not so lucky — we live at its beck and call. Hatred need only hold out an expectant hand, and we give over the keys, letting it joyride our brains. The inoculation against hatred is something far less thrilling than the sensation of being swept away with righteous anger, vindictive fury, or condemnatory rage — understanding.

The more you come to understand someone, the harder it is to hate them. The more you come to understand their backstory, circumstances, motivations, point of view, mitigating factors, and the causal chain that led them to where they are, the more difficult it becomes to see them as evil, subhuman monsters, and the more you start to see them for what they really are: complicated, flawed, human.

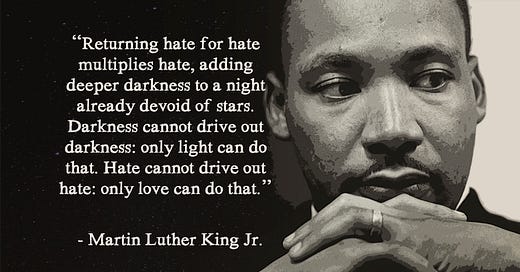

Various religious or spiritual figures, most famously Jesus, have preached that we should love our enemies. Perhaps that is taking it too far in the other direction. A better and more realistic ideal would be to relinquish our hatred of our enemies — to take the time to understand them. Understanding does not necessarily lead to love, but it leads away from hate, which is in the right direction. Hatred doesn’t solve problems, it only deepens them or creates more.

Many people struggle with the truth — and it is the truth — that everyone we dislike: from creeps, to miscreants, on up to criminals, predators, even killers, are all themselves victims. Victims of genetics, environment, upbringing, biology, and bad luck. Only by recognizing the humanity in those we look down on, dislike, or even hate can we best address the root causes and try to fix or mitigate them. Hate and disdain are easy. Understanding is more difficult, but it yields better results. If hatred had the capacity to solve problems, there would be no problems left. Goodness knows we have more than enough of the stuff to go around. But it’s hard to let go.

Hatred can feel satisfying, invigorating, even intoxicating. An escape. Sometimes we don’t want to understand, because we don’t want to give up our hate, clinging to it like a drug. It takes a kind of courage to let go of something you cherish for a greater good. Thieves, swindlers, crooks, bitter adversaries, bigots, traitors, betrayers, abusers, rapists, killers, and terrorists — most of us hate these people. And we like our hate. It feels good to hate them. It feels gratifying, purifying; right. Like a righteous flame that burns away the rot. Look at the comment section to any news article or social media post about one of the aforementioned, and you will behold sentiments in no way out of place at a medieval public execution, a witch-burning, a pogrom, or a lynching — all expressed by individuals who feel themselves to be moral, on the right side, and, on some level, committed to the project of making the world a better place.

Bucking against these impulses and intuitions seems a violation of something deep within us. Part of living an examined life is having the curiosity to question why things are the way they are — even within our own minds. It entails the thoughtfulness and discipline of examining ourselves, and realizing when something is, upon closer inspection, not conducive to the goals we claim to hold, or the kind of world we want to live in. The choice we have is one we so often face in life: do we indulge in what feels good with no thought for the effects outside that moment, or do we aspire to a higher ideal? Living an examined life isn’t about always getting it right. It’s about taking the time to stop and ask the question — and then making an effort.

See also: “Pride Goeth Before a Fall”

Subscribe now and never miss a new post. Please also consider sharing this on your social networks, it would be a huge help. You can reach me at @AmericnDreaming on Twitter, or at AmericanDreaming08@Gmail.com.