Performatively Troubled

A triple-header post, also including "The Limits of History" and "Gastro-Epistemology."

While my writing here on Substack is paywall free, there is the option to be a paid subscriber. If you enjoy my work and want to support it further, I would greatly appreciate it.

This week’s post includes three short essays. When you reach the end of this one, keep scrolling.

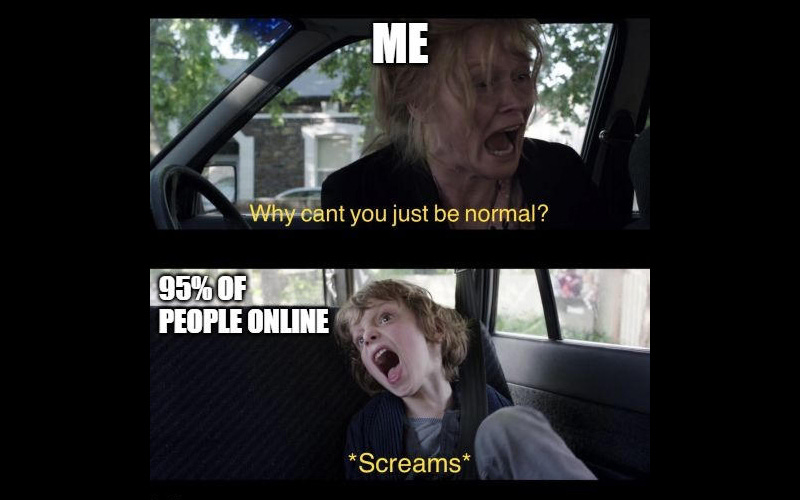

I’ve always considered myself a bit eccentric. Then the internet said “Hold my beer.” Apparently, I’m the most boring, stable, well-adjusted, neurotypical person who ever lived, graded on this curve. I still find this astonishing. Am I the only person who had a pleasant, relatively un-noteworthy childhood? Am I the only person not chronically beset by serious mental health issues? Am I the only person whose personal life or backstory isn’t a house of horrors? Damned if it doesn’t feel like it every time I log on. It’s enough to make you depressed. Maybe there’s something to that.

Victimhood, ending stigma, and sharing and caring are all in vogue these days, but I wonder if these things don’t all compound with one another in online spaces to create a sort of feedback loop and self-fulfilling prophecy. When you’re bombarded from all angles with the seeming tragedy, despair, and trauma of others, you start subconsciously looking inward to try to reframe things from your own life in ways that would catastrophize or medicalize your normal human experiences or quirks so as to fit in, or score sympathy points, or relate to people.

I’ve even caught myself doing this, in small ways. Out of pure amusement, I once drafted a fictional Twitter bio that leveraged every possible victim point I could realistically muster, with only slight embellishment. I never hit the update button, of course, but it was illuminating to see how warped a picture it painted. Anyone looking at it would see my life defined by a short list of true or mostly-true facts about myself, but ones that leave an impression bearing zero resemblance to my actual life. Nobody wants to feel like a total martian, and on the internet, if you don’t have a solid résumé of disorders, issues, tragedies, or crises to recite to anyone who’ll listen, you are a sort of outsider.

Are we creating more mental health issues in this way, or even encouraging people to embellish or fabricate their woes? I don’t see how we can’t be. Everyone’s a survivor of this, a victim of that, a sufferer of X, or going through Y. The most privileged people in human history spend their days telling the world how rough they have it, like an endless loop of Monty Python’s “Four Yorkshiremen” sketch, except purged of all humor.

What began organically as a trend of greater openness, visibility, awareness, and sensitivity seems to have fed into this online culture where people gain attention and prestige for having certain kinds of problems. Everyone has their struggles, of course. I’m not saying we should adopt the attitude of our grandparents’ generation — of buried feelings, white knuckles, and riding out rough patches alone. But there’s got to be a healthier middle-ground between that, and the nauseatingly soft, performative whining (and likely wolf-crying) that one drowns in every time they log onto the internet.

The Limits of History

The point of insight, knowledge, and wisdom — of understanding — is to be put into action, to be integrated into one’s life. To understand something without acting on or from that understanding is an intellectual failing, and in some cases even a moral one. Indeed, to learn but not to grow is not to have fully learned. The incorporation of understanding into how one thinks and acts is the final step of the process. Otherwise, the project of understanding is fundamentally no different from any act of pure diversion and distraction — a form of entertainment and nothing more. There is a special kind of foolishness in using the pursuit of understanding in this way, like buying a car only to use it for the radio.

In striving to understand various subjects, we often look to history. The person seeking to understand the present is often drawn to studying the past. The inference is that learning about something’s development, or origins, or the origins of its origins will confer the necessary understanding. This intuition is incomplete; more often than not, it won’t. Even the most rigorous interdisciplinary exploration of something’s history provides only a fragment. This is not to say that the learning of history is useless — cue regurgitations of George Santayana’s famous platitude — quite the opposite. History matters enormously. But while learning the history of something is useful for understanding it, at a point you reach diminishing returns.

History is a never ending rabbit hole, and if you’re not careful, you can lose yourself down it. It’s relevant for gaining some context and a more complete perspective, but most of the insight into a thing generally comes from observing it as it is right now. If you want to understand something in the world today, the majority of your attention should be spent on that thing in the world today, utilizing history as a tool, one of many, but not a guide. Again, the true goal of understanding is for it to be integrated into how one thinks and acts in the world. It’s easy to lose sight of that. Don’t confuse a subject with the history of that subject.

Gastro-Epistemology

The reasoning that science deniers the world over cling to is the faulty logic “Scientists or experts were wrong about [insert some past error], so they must be wrong about [insert current science]!” We see it with climate skeptics, anti-vaxxers, flat-Earthers, creationists, and IQ-deniers, among others.

It only takes a moment’s reflection to realize that every field of science, scholarship, research, and knowledge has been wrong about things in the past. So let’s think this through. If it’s reasonable to deny current findings solely on the grounds that experts have been wrong in the past, then by extension, all fields of inquiry must be useless, because they’ve all been wrong before. The logical endgame is the position that we have no basis upon which to ever determine what is true or false outside of whatever appeals to us. We can call this gastro-epistemology: if your gut tells you it’s true, just go with that. And when you delve into the alternative explanations and ideas that science deniers prefer over what the actual data says, this is precisely what we find: gut-based beliefs arrived at via gastro-epistemology.

The point isn’t that areas of human study are not or cannot be in error — they obviously have, and obviously can — but to use that as the basis for rejecting findings you don’t want to hear only advertises your unseriousness as a thinker. If a piece of science is wrong, you have to demonstrate that the evidence doesn’t add up to the conclusions drawn, or that the methodology is flawed, along with a compelling argument and/or evidence as to why and how that is. If all you can bring to the table is “They were wrong before!”, at least do us the favor of learning balloon animals to round out your act.

See also: “The Serial Killer and the Jaywalker”

Subscribe now and never miss a new post. Please also consider sharing this on your social networks. You can reach me at @AmericnDreaming on Twitter, or at AmericanDreaming08@Gmail.com.

Now I want a Monty Python sketch on victim culture, with each of them adding more labels that indicate what an oppressed person they are. Bonus points if, after all the (white) people have collectively listed all their disabilities, mental conditions, intersectionalities, and trans-* identities, a black person just walks by and looks at them.