The Case For Retiring "African American"

Hyphenated Americans, tortured language, and a plea for clarity

This post is by Contributor Timothy Wood.

Most people aren’t jerks, and while “offense” may be overused as a rhetorical device these days, it doesn’t completely delegitimize the desire not to offend our friends and neighbors, because that’s the sort of thing people care about when they’re not jerks. But that doesn’t constitute an excuse to mangle the English language. This brings us to the term “African American”, which is simply bad language. It’s an awkward construction, it doesn’t mean what we use it to mean, and it’s founded in some history that is, well, kind of racist. It’s time to retire it.

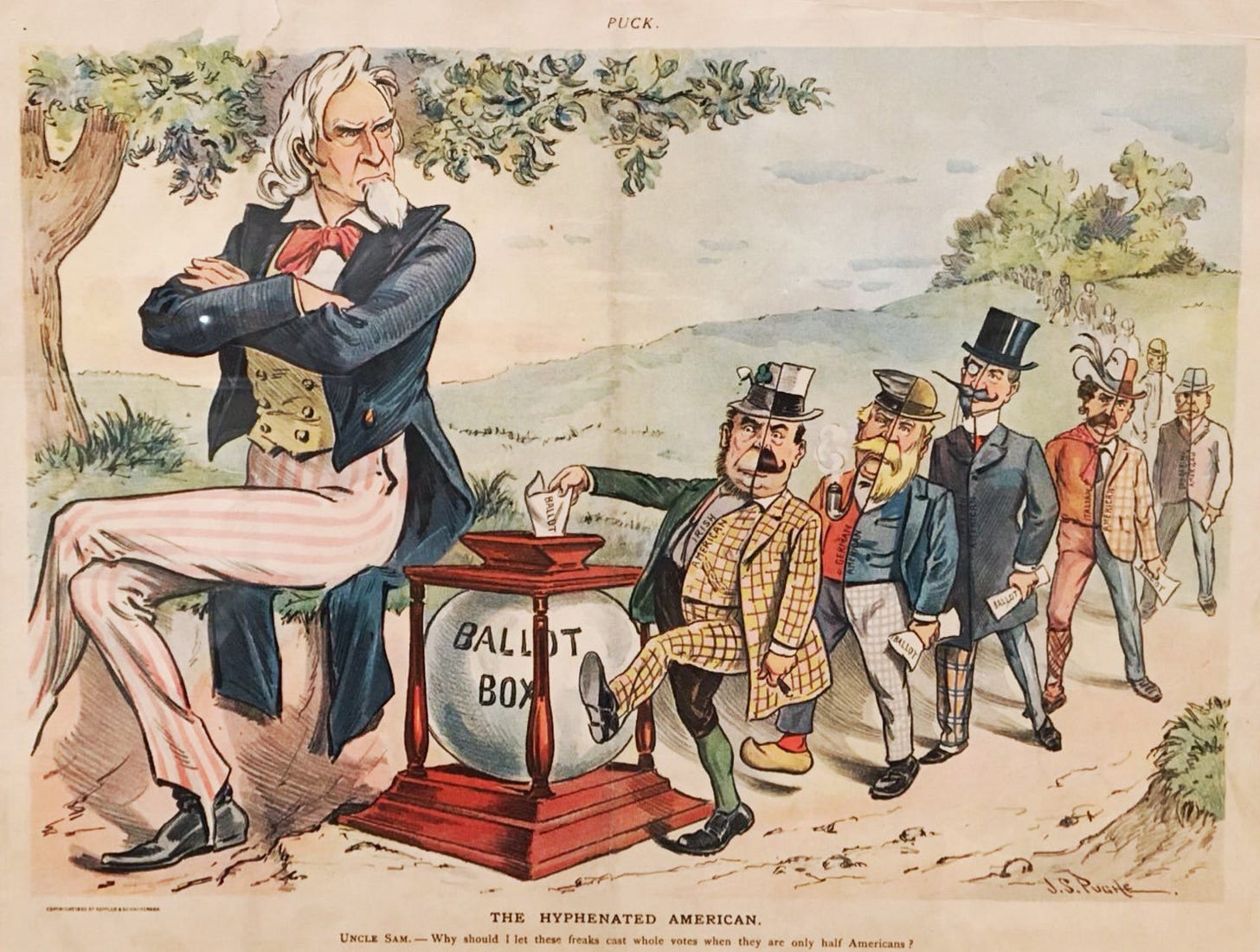

The ethnonym “African American” first appeared in the Oxford English Dictionary as early as 1835. It was later popularized toward the end of the 20th century, especially by Jesse Jackson in the 1980s, who rightly pointed out its preferability to, shall we say, “other historically popular alternatives.” It also fit quite nicely into the menagerie of terms for hyphenated Americans traditionally applied to whites: Irish-American, German-American, Italian-American, etc.

But in its own way, “hyphenated Americans” originated as a deeply racist construct. It did not, in its time, imply that you were an American with extra flair. It very clearly implied that you were semi-American and quasi-American; someone with dual loyalties that lie elsewhere. While this is historically illustrated in persecution of European immigrants, especially from Catholic countries, it still hadn’t given up the ghost when the US was putting Japanese-Americans in concentration camps as potential/assumed quasi-Americans of questionable loyalty. Let’s not forget that there were many white people who still weren’t quite white enough for the likes of the KKK. Once upon a time, white folks descended from the settlers of the original 13 colonies called themselves “Native Americans.” And they pronounced, draped in flags and dripping with bile, that no one could be loyal to America and pay homage to the whore of Rome.

“African American” also fails the language test in a number of other ways. First, it’s simply inaccurate. Amid all the squabbling over the “correct race” of then-Democratic vice presidential candidate Kamala Harris in 2020, no one pretended that we would have had this discussion about a Dutch guy from South Africa, or an Arab-Berber lady from Morocco. Lest we forget our geography, both these countries are in Africa. But people on social media — obviously renowned for their nuance and attention to detail — wanted to debate whether Harris was actually African American, because her ancestors were Jamaican. An astute observer may ask “Where do you think the black people in Jamaica came from?” But there’s somewhat more there under the surface if we dig a little.

My landlord in college — to whom I will be forever grateful for letting me count my dimes and pennies to give him 50 bucks a month until I could pay off a piano that I still treasure — mostly identified as either Jamaican or West Indian. He grew up in a West Indian diaspora community in New York City before inexplicably moving to Southeastern Kentucky as a young man. He typically visited Jamaica at least once a year. That was his heritage and those were his people.

Alternatively, one of my early friends in the military was from Lagos, Nigeria. His identity was proper African. He also regularly traveled back to his ancestral “home base” to see friends and family. That was his heritage and those were his people.

These two men, both of whom helped me grow as a person in their own way, have very different narratives. They were both dark skinned, and they may face many similar adversities in a society where discrimination based on skin color persists. But they are culturally and historically distinct. The challenges they share are based on skin color, not on cultural identity.

The term “African American” is an implicitly Eurocentric nod to the “nation of Africa”, where those who don’t know and don’t care treat the continent as a monolith, never mind the scores upon scores of distinct ethnic, linguistic, cultural, and religious groups. It ignores a complex history that saw something like 15 million people in Portuguese-speaking Brazil identifying as preto (black) or pardos (multiracial). Are you going to look at Portuguese-speaking Brazilians and call them African Americans? That’s not their story, and it’s presumptuous to think you know what their story is based on the color of their skin. This isn’t relegated to backwoods illiterates, but also quite famous illiterates, like when Sarah Palin apparently didn’t know that Africa was in fact made up of more than one country.

I am an American; I am not meaningfully a North American. And please, don’t just gloss over the difference between other ethno-linguistic groups, from French speakers in Quebec to Spanish speakers in El Salvador. We don’t eat the same food. We don’t listen to the same music. We don’t speak the same language (my Spanish is bad, but my French is proper shit).

I’m quite excited to go back to Mexico this summer. It’s 10-out-of-10 the best place to go on vacation. But me and the dude making the greatest margarita in history are not going to see each other as best mates just because we’re both from the same continent. My guide to Chichén Itzá was quite keen to let me know that he comes from pre-Columbian peoples and is a citizen of Mexico, but is not a Mexican, because — and this really ought to go without saying — a continent is not a meaningful way to group these kinds of things.

“African American” is also culturally far-removed from the group it’s supposed to describe. There are no songs about how Jay-Z is “young and African American and his hat’s real low” or Ice Cube testifying before the court of NWA about “African American police showin’ out for the white cop.” There is no African American Lives Matter, African American is Beautiful, African American Power, or African American Panthers. “African American” has become the quintessential term that non-black people use to describe black people because they’re uncomfortable saying “black”, which is what a majority of black people prefer to call themselves when asked to choose between the two.

Linguist Steven Pinker has referred to this type of phenomenon as the “euphemism treadmill” where “People invent new ‘polite’ words to refer to emotionally laden or distasteful things.” What does it say about us as a society that one person looks at another and says “I need to use a euphemism for you because you, and/or the subject of you, is emotionally laden and/or distasteful”?

In the words of another linguist, John McWhorter:

“We are not African to any meaningful extent… To term ourselves as part ‘African’ reinforces a sad implication: that our history is basically slave ships, plantations, lynching, fire hoses in Birmingham, Ala., and then South-Central Los Angeles, and that we need to look back to Mother Africa to feel good about ourselves.”

I’m not at all saying that we should get on board the critical social justice train, full steam ahead. I am making an Orwellian argument, though not the kind that name is generally associated with. When he wasn’t writing dystopian masterpieces or political treatises, Orwell wrote quite a bit on the subject of writing itself:

“Modern English, especially written English, is full of bad habits which spread by imitation and which can be avoided if one is willing to take the necessary trouble.”

In his rules for writing:

“Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print… Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.”

We do not write about Elon Musk, born in Pretoria, as an African American. That’s not because it’s more than a little awkward to dive into a lengthy debate about an apartheid era emerald mine, but because when we say “African American” what we really mean is black.

We don’t talk about Dave Matthews, born in Johannesburg, as African American. Don’t get me wrong, I like Dave. He’s one of my guilty musical pleasures. In high school, in true 90s fashion, there was a hierarchy of budding guitarists largely determined by how many Dave songs you could play. I painstakingly learned to contort my hand in completely unnatural ways to play chords that, to this day, I still remember, but can’t identify. (And of course no, I did not get the girl I was trying to impress.) But Dave is the whitest guy on the planet. If Mike Pence, Jimmy Buffet, and a sheet of printer paper needed a photo op and wanted to feel less white, they would pose next to Dave. His drummer, Carter Beauford — who it should be mentioned is a god in his own right — is a black man born in Virginia. So the black guy behind Dave is African American, but the sheet of printer paper with the guitar who was actually born in Africa isn’t? Welcome to life on the euphemism treadmill.

When we write and speak, we should say what we mean and mean what we say. In the words of dear Friar Lawrence, “Be plain, good son, and homely in thy drift.” And it’s more than a little condescending (read: culturally neo-colonial) for a largely white, left-leaning cohort so obsessed with self-identification in every other area, to essentially look at Run DMC’s “I’m black and I’m proud”, or James Brown’s “Say it loud, I’m black and I’m proud”, and inform them that this isn’t the preferred terminology in polite company. “You need to be more careful or you might make someone uncomfortable, especially those of us who aren’t African American black.”

See also: “Who Is a ‘Real’ American?”

Subscribe now and never miss a new post. You can also support the work on Patreon. Please consider sharing this article on your social networks, and hit the like button so more people can discover it. You can reach me at @AmericnDreaming on Twitter, or at AmericanDreaming08@Gmail.com.

Also, when people say African American, they only mean sub-Saharan people. Moroccans, Egyptians, etc. are labeled as MENA instead, which causes even more confusion.