The Lessons of New York City's Mayoral Battle

What went right, what went wrong, and where we go from here.

The 2021 Democratic New York City mayoral primary is over. Eric Adams narrowly defeated Kathryn Garcia in the final round of ranked-choice voting. The NYC mayoral race itself is practically over. Republican cat fancier and beret aficionado Curtis Sliwa, who will be running against Adams in the November general election, has about as much chance of victory as Donald Trump does of winning the Boston Marathon. Eric Adams is, for all intents and purposes, the presumptive future mayor of New York City.

For much of the race, however, Andrew Yang held a commanding, even prohibitive-seeming lead. He ended up finishing in fourth place. What the hell happened? What went wrong for Andrew Yang? What went right for Eric Adams? What lessons should we take away from this frenzied primary cycle, and what broader implications might there be?

What Went Wrong for Andrew Yang

Yang’s Mistakes. Andrew Yang made his fair share of mistakes and miscalculations in his run for mayor. For one, he banked too heavily on votes from the Asian and Orthodox Jewish communities, both of which he won, but blocs who typically do not turn out in high percentages. For another, Yang didn’t just lean into his naturally cheerful and sunny persona, he descended to its very depths in a deep-sea diving bell. The problem was, he was running in New York City, not Salt Lake City. He misjudged the mood of NYC politics, and how his personality clashed with the ambient level of jaded, pugnacious, angry cynicism shrouding the city’s political scene. If NYC were a person, it would be Joe Pesci from Goodfellas crossed with Patty and Selma from The Simpsons. Beaming optimism has limited appeal to a city that prides itself on assholism. There were other mistakes that bear addressing.

Campaign Management. Andrew Yang decided to go conventional, hiring Tusk Strategies, the firm who ran Michael Bloomberg’s successful 2009 mayoral re-election bid. Yang flew to the top of the polls early on, riding name recognition and high favorability ratings, and his management ran not to lose rather than aggressively running to win. Yang was running against the establishment — anyone could see he was facing a months-long blitz of attacks. Playing it safe was not the optimal strategy.

This was his Tusk-run campaign in microcosm: Superstar comedian Dave Chappelle, Yang’s friend and 2020 endorser, offered to fly to New York and do comedy shows for the campaign, but Yang’s managers turned him down, saying it was too controversial. This wasn’t just looking a gift horse in the mouth, it was ball-tapping it from behind and getting kicked in the chest. It was as though Andrew Yang was being advised by an actuarial textbook, Ben Stein’s disembodied voice, and the still-timid ghost of Union General George McClellan. Also dubious was that one of Yang’s campaign co-managers, Sasha Ahuja, a critic of his prior to being hired, appears to have been a supporter of competitor Maya Wiley. With friends like these, who needs enemies? That Yang didn’t override his foolish consultants more often shows a failure in judgement.

The “Israel Tweet.”

I'm standing with the people of Israel who are coming under bombardment attacks, and condemn the Hamas terrorists. The people of NYC will always stand with our brothers and sisters in Israel who face down terrorism and persevere.

I'm standing with the people of Israel who are coming under bombardment attacks, and condemn the Hamas terrorists. The people of NYC will always stand with our brothers and sisters in Israel who face down terrorism and persevere.This tweet produced an explosion of incandescent rage, and Andrew Yang trended nationally for several days after it, with popular hashtags like #YangSupportsGenocide, illustrating the utter lack of good faith (and dictionaries) on Twitter. Some believe this to have caused his downfall, but there’s reason to believe it wasn’t quite as damaging as the online blowback suggests. Yang was already well into his decline in the polls by this point, for reasons discussed further below. The fact that this tweet went over like a Roman candle in an oil refinery says more about Twitter and its users than it does about the tweet. Twitter is not real life. A recent poll shows that 75 percent of the US is pro-Israel, and while New York is a left wing bastion, it’s also home to one of the world’s largest Jewish communities.

Andrew Yang’s Israel tweet was in no way out of sync with mainstream political thought, even among Democrats. The fury was mostly among people hostile toward Yang to begin with. In hindsight, he would have been better off just not weighing in. What the hell does the mayor of New York have to do with Israel, anyway?

Straying From His Roots. One criticism is that Andrew Yang’s mayoral run lacked the spontaneity and charming weirdness that endeared people to his presidential campaign. This confuses the positions and goals of these two campaigns. When he ran for president, Yang was a nobody with no money and few connections who ran his campaign like a scrappy start-up. His mailing list was his Gmail contacts list. He would tell people he was running for president, and they’d respond “President of what?” When he ran for mayor, he entered the race as a national public figure and front-runner. He ran a long shot campaign for president primarily to advance an idea (universal basic income), and he was able to do that without getting many votes. When he ran for mayor, he really was trying to win. That’s why it’s hard to compare the two. Yang made mistakes. His mistakes cost him votes. But did they, on their own, cost him enough votes to lose?

The Media and Activist Class. Yang was not part of the NYC political establishment and did not dutifully climb the ladder the way city machine politics dictate. To the elite NY press, who see themselves as the cool kids table in a middle school cafeteria, Yang was this jumped-up nerd who suddenly got more popular than he ever had a right to be, and they were determined to put him back in his place. Yang also made the far-left’s shit list during his presidential run over his outside-the-box ideas and skepticism of identity politics that often put him at odds with their orthodoxy. The New York Times began running hit pieces when Yang was just rumored to be running for mayor. Another was released on the day he formally announced, and they did not relent. It’s barely exaggeration to say that nine articles in ten covering Yang were negative.

A succession of non-scandals were fabricated to feed into this perpetual motion machine of anti-Yang hate. Yang visited a corner store, referring to it (as its immigrant owners do) as a “bodega” (the local term). This became a scandal, somehow. How dare he refer to this establishment as a bodega! It’s merely a convenience store! While campaigning, someone approached Yang on the street and made an off-color joke. Yang laughed nervously and signaled the interaction was at an end. Scandal. How dare his reaction not be a sanctimonious soap box speech! In a debate, Yang cited the prevalence of street assaults perpetrated by mentally ill homeless men, saying that more resources were needed to help them, and that New Yorkers have the right to walk down the street without being brutally attacked. Scandal. Andrew Yang hates the mentally ill! Yang was asked his favorite subway stop in an interview. He answered his home stop — Times Square. Scandal. What a faux-New Yorker! What’s his favorite pizza joint? Sbarro?

This led to a racist political cartoon in the NY Daily News, depicting Yang as a caricature of an Asian tourist in New York, a city he’s lived in for 25 years. Yang not being an authentic or “real” New Yorker was a constant drum beat from the media and the left — hearkening to the bigoted trope of the “perpetual foreigner”, a prejudice particularly prevalent against Asian-Americans. Sometimes it was online progressives whipping up bullshit which was then picked up by journalists and run with. Other times it was the press churning out hit pieces and the online left gleefully amplifying them into virality. The incident that perfectly distills it all happened when a photo surfaced of Yang walking with a city official, likely discussing a possible endorsement, and a former New York Times reporter, saying the quiet part out loud, tweeted “I hope [she] pushes him into traffic.”

Lack of Government Experience. When asked what the most important attribute of a political candidate is — experience, ideology (including policy positions), or being an outsider — 28 percent of Democrats or Democrat-leaning voters say that experience is the most important thing, compared to only 4 percent of Republicans and GOP-leaning voters. By virtue of never having held political office, close to a third of the electorate is unlikely to have ever considered voting for Andrew Yang as their first choice. His résumé may have lost him more votes than his campaign mistakes and media/online treatment combined.

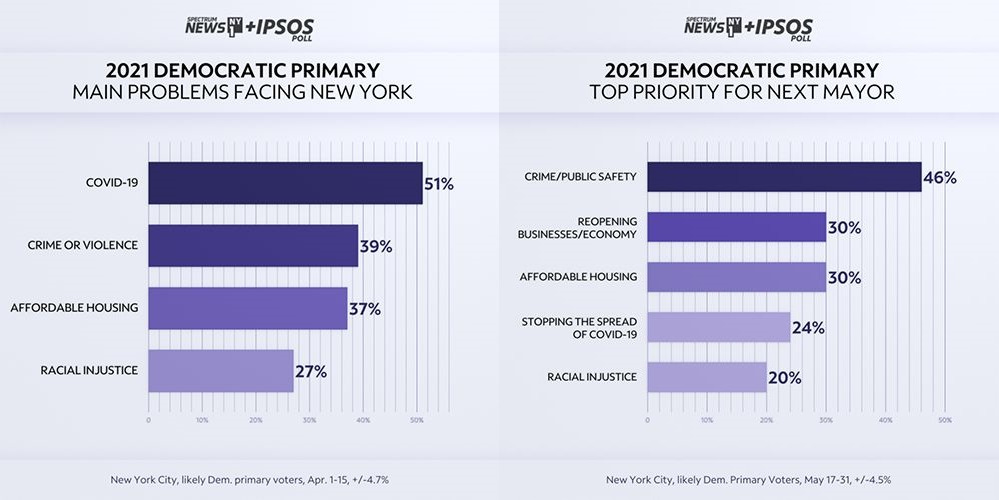

The Shifting Dynamics of the Race. During the course of the primaries, the race shifted around the candidates in ways that may have single-handedly doomed Andrew Yang’s candidacy. When he entered the race, in January 2021, the US — and New York specifically — were in the throes of the worst Covid-19 spike thus far in the pandemic. Restrictions were in effect, schools were closed, businesses were shuttering, people were suffering, and vaccines were not yet widely available. Andrew Yang staked himself out as the Covid recovery candidate, championing cash relief and other anti-poverty policies, Covid-specific proposals, reopening schools, and helping small businesses weather the storm. Then everything changed. Vaccines were rolled out, the weather warmed up, and Covid was beaten back. Restrictions lifted, masks came off, infection and death rates fell. Life returned to a semblance of normality. As the city opened up, crime began to rise. Voters routinely cited crime as their top concern. Look at this before and after:

This shift in voter priorities tracks perfectly with the decline of Yang and the rise of Adams, the former police officer with a tough-on-crime reputation. Yang found himself without a viable lane to run in. The Covid race became the crime race — one that Yang was ill-suited for. While he pivoted, changing his rhetoric and messaging to be more crime-oriented, it wasn’t enough. The race had moved out of his wheelhouse and into Adams’s. If crime is your top issue, you’re going to vote for an ex-cop who’s been talking about crime for years over a political-outsider who just started engaging with the issue a couple months before. If the stars had otherwise aligned for Yang — had he run a better campaign, made fewer mistakes, gotten fairer treatment from the press, and had some prior government experience to put on his résumé — he might have been able to overcome this. He still might not have. It probably would have been very close.

What Went Right For Eric Adams

Unplugged Normies. There are a lot of people who just go about their life, don’t follow the news very closely, don’t live online, and aren’t hyper-political. Many of these people vote, and they tend to vote based on familiarity and moderate views. Eric Adams had been a player in the New York political scene for 15 years. He was a familiar face, the most conservative Democrat in the field, and a former NYPD officer during a time of rising crime. These unplugged voters were not reachable on Twitter, didn’t read the New York Times, and could care less what far-left activists think. And they showed up for Adams in a big way.

A Large and Fractured Field. The primary field was large, and yet Adams had a lane all to himself — he was the only unapologetic centrist. Every other major candidate either ran as a progressive or pandered to them. This gave Adams a huge advantage, but he was still easily beatable, if only the left had the capacity to show a little pragmatism and consolidate against him (an “if” the size of a galactic supercluster). Needless to say, that didn’t happen.

At first, the left’s support was split between Scott Stringer and Diane Morales, both of whom imploded. Stringer was twice accused of sexual assault, the first of which he denied, the second of which he didn’t, pleading instead that it was “From 30 years ago.” Diane Morales apparently didn’t know how to run a campaign, and internal blowups and dysfunction lost her the confidence of voters.

This left Maya Wiley, who nailed the progressive aesthetic more so than the actual substance. She failed every litmus test progressives claimed to care about: she was a Clinton supporter in 2016, a vocal critic of Sanders in both 2016 and 2020, a Cuomo supporter over progressive challenger Cynthia Nixon, and declined to offer full support for the NY Health Act (a state-level single-payer universal healthcare bill). But she passed the only progressive litmus test that mattered: her name wasn’t Andrew Yang. It didn’t matter that Andrew Yang voted for Bernie in 2016, voted for Nixon over Cuomo, voiced his support for the NY Health Act, and had an anti-poverty platform that, while unorthodox, was the most progressive in the field. Like the rural working class they so often malign, the NYC left voted against their own interests and shifted their support to Wiley.

As Adams seemed poised to win, Yang formed an alliance with Garcia, admonishing his supporters to rank her as their second choice. When Yang was eliminated in the later rounds of the ranked-choice tabulation, nearly half of his voters shifted to Garcia, sending her to the final one-on-one round against Adams. Wiley, who ended up finishing in third place, turned down the opportunity for any alliances. Eric Adams ended up narrowly defeating Kathryn Garcia by less than one point. A Wiley-Garcia co-endorsement could easily have pushed Garcia over the edge, and as Adams had the most skeletons in his closet and was the least progressive candidate, Garcia would have been vastly preferable. The failure to form this strategic alliance was both the least progressive thing Wiley could have done, and yet, the most quintessential progressive thing ever.

Adams Flew Under the Radar. Eric Adams had a history of suspect associations, troublesome and controversial remarks, and corruption investigations. The dude had more baggage than JFK International. And yet the New York voting public, by and large, was unaware of it. The media’s all-consuming obsession with Andrew Yang sucked all the oxygen out of the room. As the press launched an all-hands-on-deck carpet-bombing of Yang, the rest of the field was hardly being covered at all. Their past scandals, current gaffes or mistakes, and criticisms of their proposals received almost no attention. Adams was benefiting from his name recognition and the shift in voter priorities due to rising crime, and facing virtually zero scrutiny.

It wasn’t until the race was entering the home stretch that the media, who almost to an individual supported Kathryn Garcia for mayor, realized what was about to happen. Shaking themselves from their psychosis, the media’s Eye of Sauron fixed Adams in its gaze. But it was too little, too late. Again, most people are not news junkies. Months of negative coverage will filter down to most people. A few weeks worth won’t. The fact that Adams, who spent half a year bashing Yang as not being a real New Yorker, appears to have been living in New Jersey for years and fudging his NYC residency, a scandal that could easily have destroyed his campaign if aired earlier, reached too few people to make a difference by the time it was covered. It is inaccurate to say that the media is primarily responsible for taking down Andrew Yang, though they played a role. But the media is responsible for a gross dereliction of duty that unwittingly ran interference for the Adams campaign.

Rising Crime. As already discussed, the decline of Covid and the increase in crime played right into Adams’s hands.

So, what went right for Eric Adams? Frankly, what didn’t?

The ‘Own Goals’ of the Media and the Left

The NY media wanted Kathryn Garcia to be mayor. NYC’s left wanted Maya Wiley. The candidate who least aligned with either group, who was most hostile to each, and who was the most corrupt, was Eric Adams. Neither Garcia nor Wiley won, and Adams did. And both the press and the left helped this happen. They both functioned as useful idiots and de facto campaign volunteers for Eric Adams.

For the media’s part, they simply couldn’t help themselves. Yang was the most sensational candidate in the field by a mile. Yang brought views and clicks, and the press, driven by monetary incentives, mined the anti-Yang beat for all it was worth, to the virtual exclusion of critically covering any other candidate. Some journalists will have the decency to show a little shame and remorse over this affair. Not that it will stop them from doing the same thing next time, and the time after that. The incentives that drive the press produce an effect indistinguishable from a formic hive mind whose queen demands profit maximization, achieved within woke parameters. It’s a deeply broken system. They wanted Garcia to win. But they wanted money, clicks, and professional prestige much, much more.

Of the activist left, whose behavior fed into the same result, albeit for more emotional and ideological reasons, no such introspection can be expected. They are incapable of it. As the preliminary results rolled in on election night, Adams had taken an imposing lead, never to be surmounted even when the absentee ballots were later counted. It also became clear that Andrew Yang had been resoundingly defeated. That night, and the day after, leftists took to their phones and keyboards in an orgy of jubilation reminiscent of Return of the Jedi. While they preferred Wiley, they appear to have been animated by a disproportionate blinding hatred of Andrew Yang above all else. To them, the defeat of Yang was victory enough. They barely seemed to care that the least progressive, most anti-left candidate won, and that their efforts, otherwise directed, might have enabled a different result — namely, Kathryn Garcia. It’s time to start the conversation: should “online leftism” be added to the DSM?

Takeaways

Trust the Polls. Confidence in political polling took a hit with the 2016 victory of Donald Trump. Ever since, every underdog campaign has drawn hope from the prospect that, like in 2016, the polls may be wrong for them, too. There are a number of methodological issues with how polling is conducted. And yet, upon closer examination, polling gets it right in the vast majority of cases. Where polling legitimately struggles is for Democrat-vs-Republican presidential polls at the state level. That remains an ongoing concern in the polling community. But national polling and intra-party primary polling remain highly accurate. The 2021 NYC mayoral primaries demonstrated polling’s accuracy yet again.

Ranked-Choice Voting Works. New York City’s use of ranked-choice voting is one of the biggest implementations so far in the US. Ranked-choice voting (RCV) is where voters can rank a number of candidates, indicating their first, second, third, etc. choices. If no candidate gets over 50 percent, it goes to the next round, where the lowest performing candidates are eliminated, and their voters’ second choice votes are transferred to their respective candidates. This process is continued, round after round, until one candidate has over 50 percent. RCV is a more democratic, more representative, superior way to vote — where you can vote your true preference (say, a long shot you really like), while also voting for your favorite candidates among the top-tier so that you’ll have a say in determining the final outcome.

But RCV does take a little getting used to, and in NYC, it did not realize its full potential. Voters could rank up to five candidates in this election, but 15 percent of ballots were exhausted by the final round — meaning that those voters’ ballots were no longer active, either because they ranked fewer than the five candidates allowable, or because they ranked five, but none of them were Adams or Garcia. As a general rule, ranking two of the top three polling candidates ensures that your vote will not be exhausted. Additionally, too few influential endorsers announced their RCV endorsements (i.e. who they endorse as their second choice, third choice, etc.) until the very end, when it would hardly reach anyone and when many people had already voted. As RCV becomes more widely adopted — as it should — voters will become more familiar with this process. Even so, and notwithstanding the NYC Board of Elections’ buffooneries in getting the results out, this election shows that RCV works.

Leftists Are Not Reliable Allies. If a candidate is not themselves a dyed in the wool leftist, or a cause does not fully align with leftist orthodoxy, any effort or time spent trying to make common cause with the leftmost 10 percent of society is a fruitless waste of time. Leftists are incapable of pragmatism, compromise, tolerating differences, and doing the work required to form effective, sustainable coalitions. They’re more interested in tearing things down than in ever building anything — and given what they believe, that’s probably for the best. Democrats need to factor this in to all their strategies from the get-go.

The Press Continues to Decay. It’s hard to imagine that very many people who followed this race were satisfied with how it was covered in the press. Unfortunately, this isn’t an aberration. The media seems to keep dropping the ball when it comes to providing accurate, evenly distributed, fair coverage. Trust in the press as an institution has fallen over the years, and they have largely brought it on themselves. The public bears responsibility, too — we are, after all, providing the clicks and revenue that drive these pernicious incentives.

Where Does Yang Go From Here? Many are wondering if this is the end of the road for Yang’s political ambitions. After all, he has run twice and lost twice, and the stink of this loss may cling to him for years. But it’s worth noting just what he’s accomplished. Three years ago, Andrew Yang was a random citizen, and nobody knew what universal basic income was. Now, it’s widely known, and supported by 55 percent of the country. Dozens of basic income trials are being launched all across the nation. Americans received three no-strings-attached checks during the pandemic, and tens of millions of families are now receiving monthly cash payments from the expanded child tax credit — in essence a basic income for kids. None of this happens without Andrew Yang. How many elected officials have served in government for decades and haven’t made a thousandth the contribution to society?

I doubt we’ve seen the last of Andrew Yang, and if his next few years are even half as successful as the past few, that’s still pretty damn good.

See also: “Andrew Yang’s New "Forward" Party Isn't What You Think”

Subscribe now and never miss a new post. Please also consider sharing this on your social networks. You can reach me at @AmericnDreaming on Twitter, or at AmericanDreaming08@Gmail.com.

Having observed this closely in real time, I completely concur with your analysis. The back-handed racism toward Asians by the identity-politics left was completely shocking to me.