The Lost Lessons of the Bath School Massacre

The forgotten story of America’s first mass killing shows that it’s not only killers who slip through the cracks.

This post is by contributor Jacob Bielecki.

It has been nearly a century since America’s first mass killing — an event that remains to this day the deadliest school massacre in US history. Yet other than the method used to carry out the slaughter, it’s a story that has become all too familiar over the years.

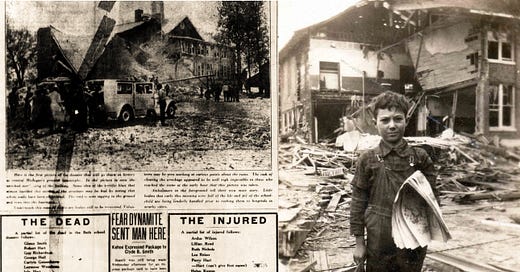

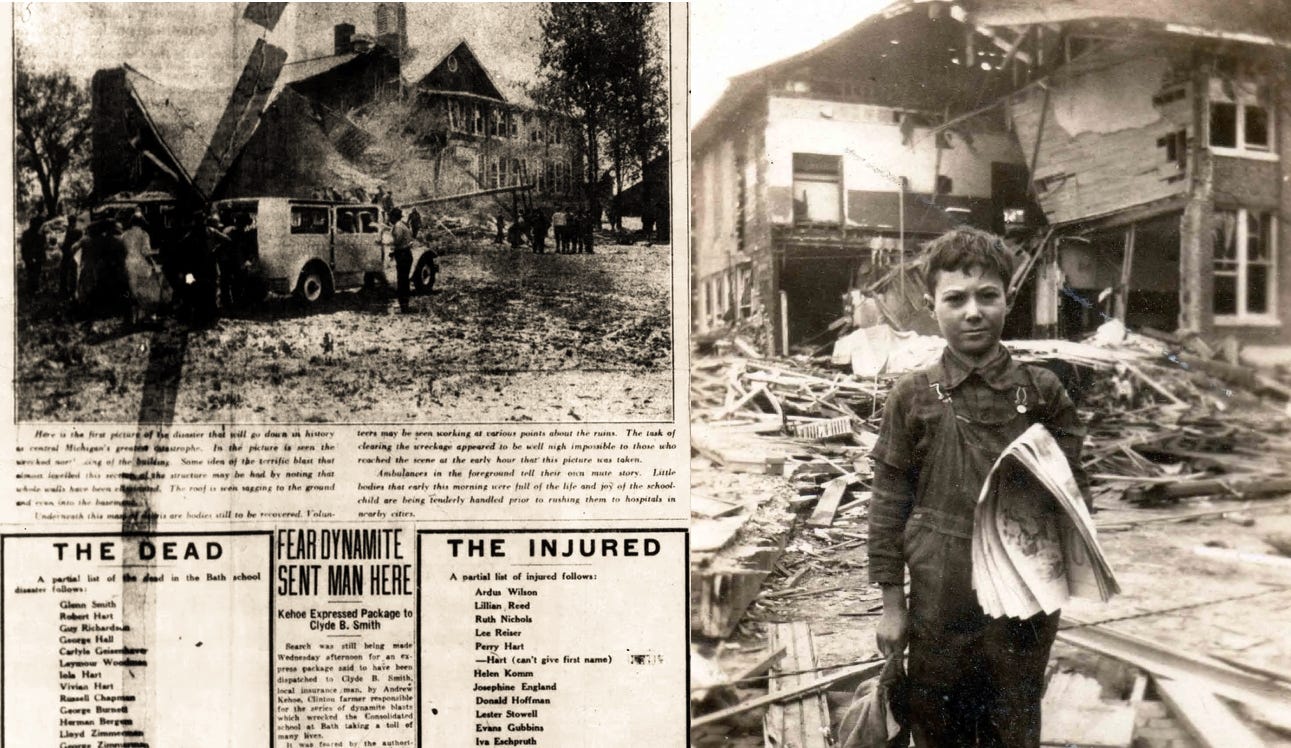

The Bombings

On the morning of May 18, 1927, residents living on the outskirts of Bath Township, Michigan, a small town of 300 people 10 miles north of Lansing, were greeted by the sound not of roosters crowing, but of a thunderous explosion. When they went to investigate the cause, they found Andrew and Nellie Kehoe’s house and the other barns on their property ablaze. Some of the neighbors crawled into the house through an opened window to search for survivors, but found no signs of life. When the neighbors departed the farmhouse, they ran into Andrew Kehoe, who suggested they go to the schoolhouse before taking off in his truck. When the neighbors looked down the road, they were horrified to see that Bath Consolidated School was on fire, too.

Bath Consolidated School taught students from second to twelfth grade. The twelfth graders were not in attendance that day, as they prepared for their graduation ceremony at a nearby church. The rest of the students were taking their final exams. Classes started at 8:30 a.m. At 8:45, the same time that the Kehoe’s farm detonated, the north wing of Bath Consolidated School exploded as well.

Teacher Bernice Sterling later told the Associated Press, “I saw the bodies of my children hurled against the walls or through windows. Then I don’t remember much what happened. The explosion stunned me, and I could not do much until help came.”

Everyone in Bath heard the explosion and immediately headed to the school to help. Among those who rushed to assist was farmer M.J. “Monty” Ellsworth, who was initially going to the Kehoe’s farm to investigate what happened. Ellsworth would later write a book about that awful day, The Bath School Disaster (1927), giving historians a crucial firsthand account of what transpired.

Parents desperately tried to free their children from the debris. According to one eyewitness, Robert Gates, who helped free several children trapped under the rubble, over 100 men and women assisted with the relief effort. “I saw more than one woman lift clusters of bricks held together by mortar heavier than the average man could have handled without a crowbar,” Gates recalled.

Monty Ellsworth and other residents tried pulling a portion of the roof that had pinned several children, but there were not enough people to move it. Ellsworth noted that he had ropes at his farm that could help, and while speeding back to retrieve them, he crossed paths with Andrew Kehoe who was driving to the school. “He grinned and waved his hand,” Ellsworth wrote in his memoir. “When he grinned, I could see both rows of his teeth.”

A half hour after the north wing explosion, Andrew Kehoe, who was a school board trustee and the treasurer, arrived at Bath Consolidated. Sources differ as to what happened next. Either Kehoe produced a rifle and got into a scuffle with school superintendent Emory Huyck, or Kehoe went to the back of his truck and fired his rifle into it. The end result was the same: Kehoe’s truck, which was packed with dynamite, exploded. The blast killed both Kehoe and Huyck, along with three bystanders: retired farmer Nelson McFarren; McFarren’s son-in-law and Bath postmaster Glenn O. Smith; and G. Cleo Clayton, an eight-year-old second grader. Smith wasn’t killed immediately — he bled to death from a severed leg before an ambulance could reach the scene. Kehoe had also loaded the truck with bolts, scrap iron, rifle shells, and other objects to cause maximum shrapnel damage to everyone nearby.

The Aftermath

Bath’s telephone operators manned their posts for hours on end, calling doctors, nurses, morticians, and anyone else who was willing to help. Dr. J.A. Crum and his wife, who had both worked in field hospitals during World War I, turned their drug store into an infirmary and, according to Ellsworth, also treated patients in their home. There were not enough ambulances to transport all the wounded to local hospitals, so townspeople volunteered to drive them in their own personal vehicles. Members of the Lansing Fire Department led by Chief Hugo Delfs arrived and used their equipment to clear the debris and rescue survivors from the wreckage. The dead were taken to the Town Hall which acted as a temporary morgue. The Michigan State Police also arrived to direct traffic to and from the school. Among the volunteers who helped clear the rubble was Michigan Governor Fred W. Green.

As first responders scoured Bath Consolidated for victims and survivors, they found 500 pounds of dynamite in the school’s south wing basement. Search and rescue efforts were temporarily halted so the police could defuse the explosives. The police found an alarm clock rigged to go off at 8:45 a.m. Investigators believed the initial blast caused the timer to malfunction.

As relief efforts continued and the dead and wounded were accounted for, Michigan State Police investigated the Kehoe farm and searched for Andrew Kehoe’s wife, Nellie. All the structures on the property were destroyed. Kehoe’s two horses were found dead in the barn, their knees bound together with wire to ensure they perished in the blaze. The police found Nellie Kehoe’s remains the next day. Her skull had been crushed a day or two before the explosions.

46 people were killed and 58 wounded in the Bath School Massacre. Of the dead, 39 were children — all 14 and under. The youngest victim was seven. Until August 22, the victim total stood at 44. Beatrice Gibbs, a fourth grader, who had been hospitalized since the day of the slaughter, died while doctors attempted to extract a splinter embedded in her hip. The day before the attack, she’d celebrated her tenth birthday. Eight-year-old Richard Fritz, whose sister Marjorie was killed in the bombing, died one year later of myocarditis. Fritz is not listed as an official victim although his condition was almost certainly brought on by the injuries he suffered in the attack.

The Bath School Disaster became nationwide news. The notion that a man would massacre school children shocked the country. The first funerals were held on Friday, two days after the killings, and continued until Sunday, when tens of thousands of Michiganders passed through Bath in their cars in a show of solidarity. Donations poured in from around the country to assist the victims and to rebuild the school. Governor Green, whose furniture business made him a wealthy man, paid for the funerals of the families who could not afford one for their children.

The authorities began investigating Andrew Kehoe’s motive for the attack on the day of the massacre. Police suspected that Kehoe may have had help in planning the bombings based on the sheer amount of explosives and the complex wiring system used to rig them. However, this theory was abandoned after police found that no one else had a motive to attack the school and that Kehoe was a master electrician who could have easily set up and detonated the dynamite on his own.

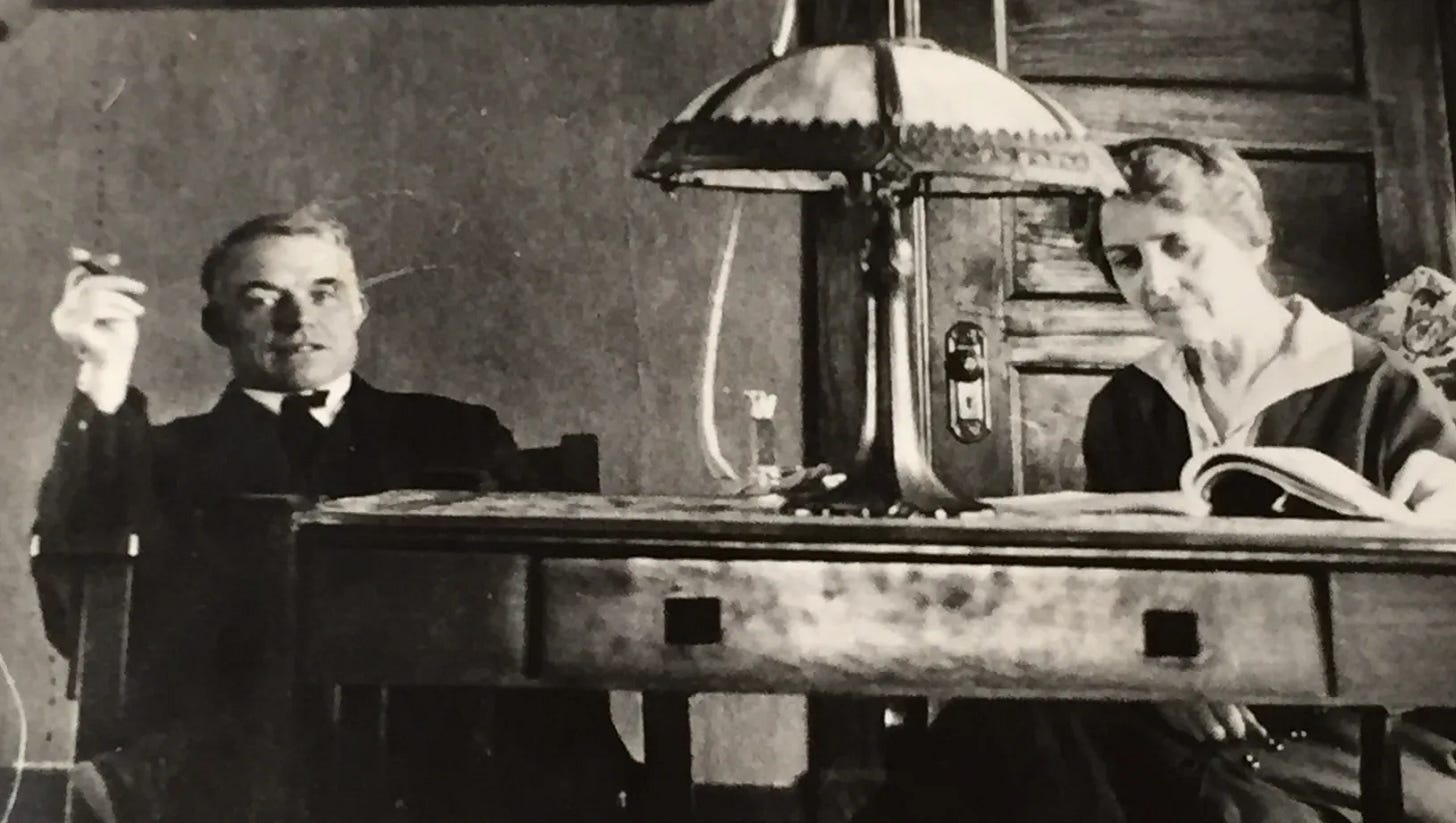

Andrew Kehoe

The investigation into Andrew Kehoe painted a picture of an arrogant and rageful man deranged by grudges, consumed by grievances, and unable to take responsibility for his actions. Born on February 1, 1872, in Tecumseh, Michigan to Mary and Philip Kehoe, Andrew was one of 13 children — the seventh child, but the first son. And as the first-born son, elevated above his siblings and given special treatment by his parents, Kehoe grew up with an inflated ego, a sense of entitlement, and the belief that he could do no wrong. Uninterested in farming like his father, he attended Michigan State University to obtain a degree in electrical engineering where he met Nellie Price, who came from a wealthy Lansing family.

Kehoe graduated and went on to work in Iowa and St. Louis. Little is known about this period of his life other than that in 1911, Kehoe fell and suffered a serious head injury that put him in a coma for two weeks. Whether or not this injury affected his personality in any way is unknown.

After recovering, Kehoe moved back to Tecumseh to live with his father. Kehoe’s mother had died during his time in St. Louis, and his father remarried a woman named Francis Wilder, whom Kehoe resented. In September 1911, Francis was severely burned when a gasoline stove she was attempting to light exploded. Kehoe doused her with water, but it was an oil fire, and this only intensified the flames. Francis died the following day from her injuries. In the decades since the Bath School Massacre, it has been speculated that Francis’s death was no accident and that Andrew Kehoe may have rigged the stove to kill her. Kehoe’s neighbors at the time, speaking with Monty Ellsworth many years later, said that they’d suspected Andrew had something to do with her death. Whether Kehoe is in fact responsible for killing his stepmother will forever be a mystery.

Andrew Kehoe married Nellie Price in 1912. In 1919, he bought a 185-acre farm outside of Bath Township from Nellie’s uncle for $12,000, despite having no interest in farming. Kehoe paid $6,000 and took out a $6,000 mortgage. He spent most of his time tinkering with his equipment. On the occasions when Kehoe did attempt to farm, he showed none of his father’s aptitude. According to Ellsworth, Kehoe tried to run his farm singlehandedly using just his tractor and various unsuccessful would-be innovations to cut corners and spare himself from having to perform any manual labor. Kehoe, Ellsworth wrote, “was always trying new methods in his work, for instance, hitching two mowers behind his tractor. […] He also put four sections of drag and two rollers at once behind his tractor. He spent so much time tinkering that he didn’t prosper.”

An explosive temper and a frugality that was downright miserly were the two traits Bath residents repeated when investigators asked them to describe Andrew Kehoe. He once shot a neighbor’s dog for annoying him, bragged about killing his stepsister’s cat, and beat one of his horses to death for not pulling a plow the way he wanted. Andrew and Nellie Kehoe attended a Catholic church in Bath when they first moved to town. However, when the parish requested donations to build a new church, Andrew refused, stopped attending, and forbade his wife from going to services as well.

Despite these red flags, Bath residents voted for Kehoe to serve as a trustee on the Bath school board in 1924. He ran for the position not out of any sense of civic duty, but to block the construction of a new school. Bath Township had elected to consolidate their individual schoolhouses into one, and the construction of Bath Consolidated School necessitated an increase in property taxes, a prospect that tormented Kehoe, who hated paying taxes. He attempted to get his property devalued to reduce his tax burden, but this plan yielded no more fruit than his fields. From 1922 to 1926, Kehoe went from paying $122.60 a year ($2,328 adjusted for inflation) in property taxes to $198 ($3,569 adjusted for inflation). Again, on a 185-acre piece of land.

Kehoe ended up serving three years as a trustee and one year as treasurer. He also served as the school’s electrician and handyman and was provided with a key. His time on the school board was fraught with conflict. Kehoe fought against any and every expenditure, leading to constant disputes with superintendent Emory Huyck and others. If any board member dared to disagree with him during a meeting, Kehoe would immediately move to adjourn. When he became treasurer, he used his newfound power to cut Huyck’s pay and vacation. He also conveniently couldn’t remember to pay Huyck on time. Unable to handle disagreement and convinced he was always right, Kehoe reacted to even modest opposition with hostility, tantrums, and petty abuses of power.

Andrew Kehoe’s antipathy to paying property taxes was compounded by the fact that he was financially underwater. And as each year went by, his money woes mounted. His poor work ethic and general ineptitude kept him from being a successful farmer. Declining crop prices only made matters worse. Nellie Kehoe also suffered from a chronic illness (thought to be tuberculosis) that she was repeatedly hospitalized for — adding to her husband’s financial headache. The exact nature of the couple’s relationship is unknown, but in Monty Ellsworth’s account of the massacre, he hints that Nellie was very much the long suffering wife. That she was found with her skull caved in another clue that life with Andrew Kehoe was far from happy.

Everything came crashing down for Kehoe in 1926. The year before, he was appointed town clerk after the previous clerk passed away. But when Kehoe ran for a new term, he was soundly defeated. Bath residents had finally grown tired of his antics. Kehoe couldn’t handle the rejection. He stopped farming and paying his mortgage and taxes. When he was served with papers informing him that his home was being foreclosed on, Kehoe told the process server ,“If it hadn’t been for that school tax, I might have paid off the mortgage.” When he delivered one of his horses to a neighbor, the neighbor thought Kehoe might commit suicide. Monty Ellsworth stated in his memoir that he believed Kehoe began planning the attack after his defeat in the county clerk election. David Harte, who lived across the street from Kehoe, also believed that he had planned the attack for some months ahead of time. As the school’s handyman, Kehoe would have had ample opportunity to plant the dynamite during off hours completely undetected. In the fall of 1926, he bought two boxes of dynamite.

While it may seem to us that surely this should have raised eyebrows if not suspicion, dynamite was frequently used by farmers at that time to clear stumps, boulders, and other debris from their property. Although Kehoe used dynamite more often than the average farmer, there was nothing to indicate that he would use it for nefarious means. On May 5, 1927, Andrew Kehoe attended his final school board meeting before his term was due to expire. He was surprisingly agreeable and in a good mood throughout the proceedings.

The Legacy of the Bath School Disaster

The Bath School Disaster only grabbed national headlines for two days before it was knocked off the front pages by Charles Lindbergh’s transatlantic flight. The rest of the country moved on — a dynamic all too familiar today. Society doesn’t want to dwell on senseless slaughter when it hits too close to home.

The massacre almost immediately became the ugly town secret that nobody in Bath talked about. Bath’s class of 1927 would not have a proper commencement ceremony until 50 years after the bombings, when they received their diplomas alongside the class of 1977. Survivors were still reluctant to go on record over half a century later.

Michigan State Senator James Couzens, a former Ford executive, donated money to build a new school that was named in his honor. It opened in 1928, but was torn down in 1975 and the James Couzens Park was erected in its place. There’s a plaque at the park listing the names of each victim. Also on display is Bath Consolidated School’s cupola. The cupola, the last remaining piece of the original school, will be moved indoors and displayed in a museum set to open on the 100th anniversary of the bombing.

As horrific and unprecedented as Andrew Kehoe’s act of terror was, he’d intended to kill every child and teacher in Bath Township. Had his second bomb gone off, he may very well have succeeded and wiped out an entire generation. Like the many mass killers who have followed in Kehoe’s depraved footsteps, he first committed smaller crimes that went unpunished. As with Columbine, Virginia Tech, Sandy Hook, and so many other atrocities, the warning signs were there for all to see, but Andrew Kehoe slipped through the cracks. The fact that the mass murder he perpetrated — the first and still worst of its kind — is now all but forgotten, shows that, in a way, we have all allowed ourselves to slip through those same cracks too. Nobody wants to assume that their neighbors might be evil. Nobody wants to take responsibility. Nobody wants to remember. So we leave broken communities to pick up the pieces and carry on.

The Last Angel

On September 14, 2014, a ceremony was held to commemorate Richard Fritz’s new and updated headstone. Richard’s nephew, Dan Osborne, was in attendance as well as Lucille Eschtruth Gatzke, whose father Walter Eschtruth survived the bombing. Underneath Richard’s name and date of birth and death it reads:

Last Angel #46 Bath School Disaster May 18, 1927

See also: “No, the Trains Never Ran on Time”

Subscribe now and never miss a new post. You can also support the work on Patreon. Please consider sharing this article on your social networks, and hit the like button so more people can discover it. You can reach me at @AmericnDreaming on Twitter, @jamie-paul.bsky.social on Bluesky, or at AmericanDreaming08@Gmail.com.