Time and the Laundering of History

Time may heal all wounds, but the lessons of some wounds are best remembered vividly.

This week’s post is by contributor Johan Pregmo.

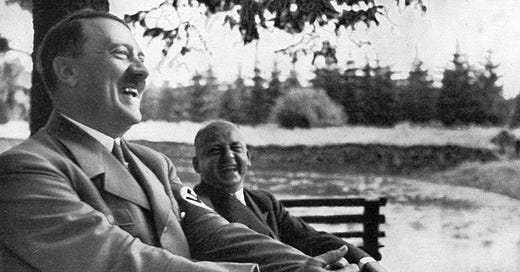

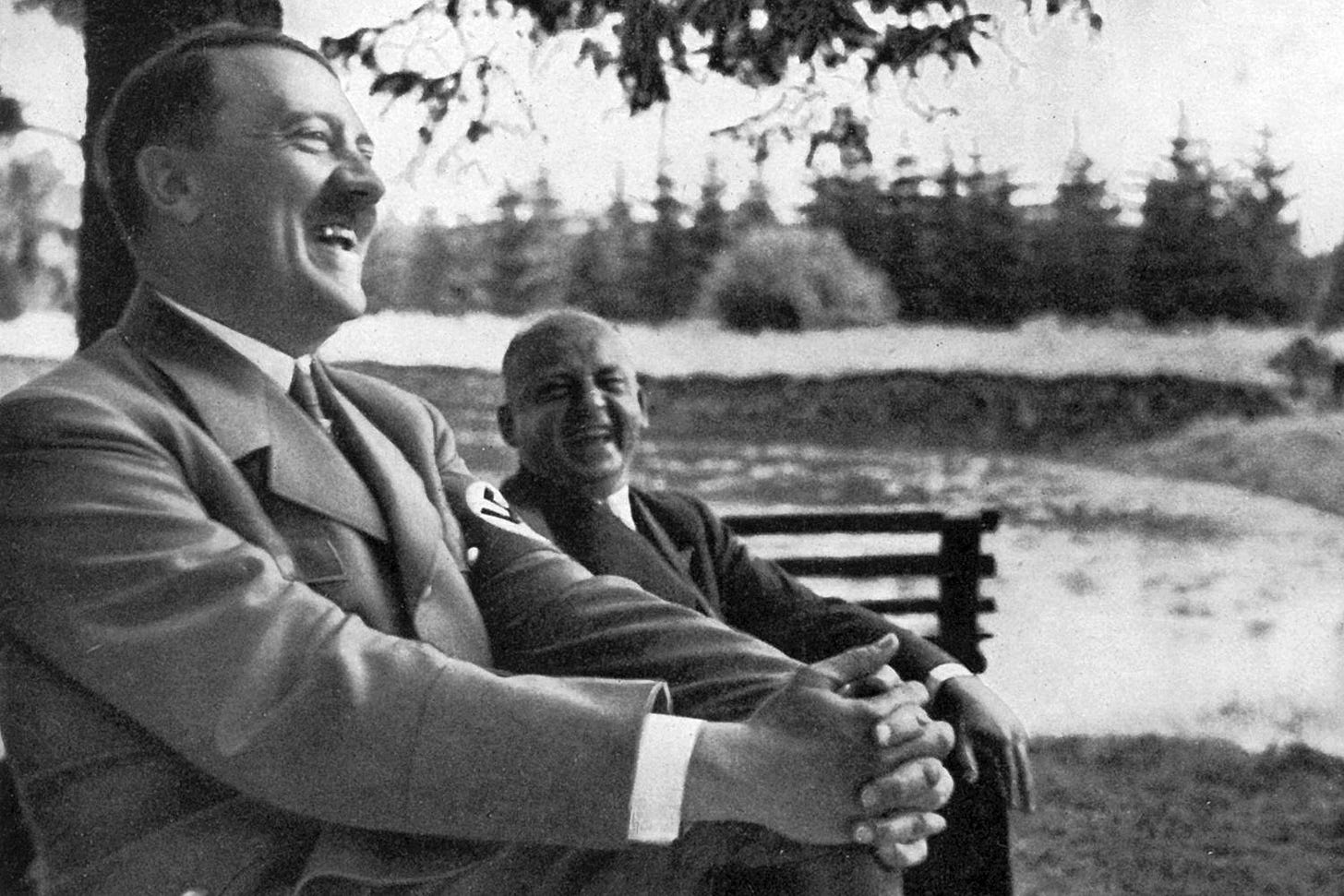

When you think of Adolf Hitler, or Nazi Germany, what immediately comes to mind?

Unless you are an actual fascist or a very specific type of contrarian weirdo, the imagery will be immediate and clear: untold dead in a war of aggression. Tyranny, racial hatred, and ruthless persecution. Horrifying images of death camps with people slaughtered by the millions. Mad ambition that drags the whole world into war. Immeasurable suffering on a global scale that boggles the mind. And a vile, lunatic monster in charge. In short, evil.

The Third Reich has provided an easy shorthand for the worst kind of inhumanity. We see it and reflexively associate it with behavior so beyond the pale as to be incomprehensible, even comical in a way. “Nazism is wrong and evil” is so embedded into the Western psyche that actual Nazis are well aware of the need to rebrand. They’re not Nazis, no, they’re the alt-right, or ethno-nationalists, or Christian nationalists, or white separatists, or just good old-fashioned conservatives who hide their true beliefs really, really well.

This is a trick of perspective. While the Third Reich is undoubtedly every bit as horrible as pop culture’s understanding of it, possibly even worse, would our loathing be as strong if they hadn’t picked a fight with the US and other Western powers? Would we have such an ingrained contempt for Nazis if there hadn’t been a generation of people in the most influential countries across the West, from the US to England to France, who had grown up with the collective trauma of the German war machine rampaging across Europe? Go to countries whose peoples never faced the Nazis up close and personal, and you’ll see that these rhetorical questions have very real answers in the negative.

History has a way of softening the reputation of its most legendary characters. When we think of Julius Caesar, we remember that he was an exceptional general, master tactician, and celebrated statesman. Little time is spent reflecting on the two million Gauls who were either killed or enslaved in his conquest of Gaul, a number extraordinary even by the blood-drenched standards of the Romans. To the Romans, Caesar was a hero of unmatched quality, a conqueror of their ancestral enemy, and a brilliant military leader. To the Gauls, he was the man who either cut down or enslaved a third of their population, the subjugator and slayer of their friends and families. And yet, history remembers Caesar mostly for the former rather than the latter. He is the gallant hero and founding father of the Roman empire, immortalized in pop culture again and again.

Consider an even more extreme example. Genghis Khan started an empire that would go on to kill between 30 to 40 million people, a number that rivals even the destruction of World War II. Entire nations were put to the torch. The Mongols conquered and ruled by force, extracting tribute or dealing out death — the very quintessence of thuggery. Even with this extravagant brutality, however, what we remember most is the extravagance of their accomplishments. Genghis Khan began life as an impoverished tribesman, scraping by on nothing, and through hard work and ingenuity he united his peoples and forged an empire. It’s a captivating rags-to-riches story.

And as a story, it’s easy to focus on just how impressive it was — how these shepherds from bumfuck nowhere ran over entire empires and became rulers in their own right. What are 30 million nameless dead compared to that? You can’t help but admire the gumption and skill. It’s exciting. The millions who died in the process blur into the background and ultimately into irrelevance. Hundreds of years removed, the millions of unmarked graves become just another anonymous blip in history. Joseph Stalin never said “The death of one man is a tragedy. The death of a million is a statistic,” but whoever did understood human nature all too well.

Perhaps the most striking example of historical reputation-laundering might be the Vikings. For two centuries they terrorized every part of the known world that was within striking distance of coast lines. They were known to their contemporaries for raping, stealing, and murdering their way across every land they found. If you were lucky, they extorted a huge sum of silver instead of pillaging you. They spent most of their time picking on divided, weakened, or militarily inferior territories that could not defend themselves. They slaughtered warrior and civilian alike. They were chickenshit raiders, a brutal rabble who built nothing of lasting value, contributed nothing to human advancement, and still they are remembered and adored by the modern public as kickass warrior heroes who epitomized martial virtue. These parasitic, rapacious extortionists, who would have crumbled in the face of any well-organized army, who indeed were ultimately beaten by better men who built far greater legacies — they get to enjoy the most positive coverage imaginable from media and fiction. I find this particularly disgusting as a Swede.

That said, I am not one to judge historical figures by modern moral standards. Men like Genghis Khan, or Julius Caesar, or Napoleon Bonaparte were products of their time, with morals of their time, driven by the political realities of their time. What set them apart was talent, drive, and ambition to take conflicts to a new level.

But it does make you wonder: how long before we could see an HBO-style series lionizing Hitler, glossing over Nazi war crimes, and depicting WWII German soldiers as stylized badasses lighting up the battlefield? Certainly not in our lifetimes. Probably not in a hundred years. But in three hundred years? Five hundred? As time passes and generations change, a gulf opens up between the visceral carnage suffered or witnessed by the victims of history’s many mass murderers and the ever more detached hindsight of those looking back from the future.

Our contempt for any particular dictator, tyrant, or butcher depends less on how destructive they were, and more on how close to home their damage was, and how far-removed their deeds are in time. Had Hitler stopped his conquests at Poland and not engaged the Western powers, would we instead remember him in the same vague and distant way we remember, say, Pol Pot? Sure, he’s a bad guy, we all know that, but the wider public doesn’t care much.

Even moving Hitler to the level of Joseph Stalin would be a reputational boost. The perception of this Russian “Man of Steel” is rather bizarre. Most people know Stalin was bad, but few know about the Holodomor, the arguably genocidal Soviet-induced famine that swept Ukraine. Few people know about the anti-Semitism in Soviet Russia, or ethnic cleansing efforts like the forced relocation of the Crimean Tatars. Upwards of 20 million people were killed under Stalin’s rule, more than in the Holocaust. Why is one mustachioed, brutal dictator remembered with less scorn than another? Presumably because we never had to fight a war against Stalin. Despite his crimes against humanity and greater body count, Stalin is nowhere near as reviled as Hitler, even though a case can be made that he should be. How long, then, until people forget the horrors of Auschwitz, Treblinka, and Majdanek and reduce Hitler to just another “bad dictator” among many others?

Or, perhaps, what if we came to think of Hitler the way we think of Napoleon? There are certainly some broad similarities. Both were dictators coming into office through a coup; both dramatically changed their countries; both enjoyed stunning military success early on before being brought down by a coalition of enemies; and both were broken by foolhardy invasions of Russia. Bonaparte once addressed an assembly of Catholic clergy by saying “I am a monarch of God’s creation, and you reptiles of the earth dare not oppose me. I render an account of my government to none save God and Jesus Christ.” Translated into German and delivered with sufficient gusto, we can just as easily imagine a variant of these words coming out of Hitler’s mouth in his bunker.

Without the magnifying lens of historical knowledge, however, it would be easy to miss the important distinctions. Napoleon was a military genius while Hitler made several dubious strategic blunders. Napoleon liberalized his country and preserved the revolutionary values as a new status quo while Hitler regressed his society into a death cult. Napoleon repeatedly sought diplomatic solutions while Hitler’s answer was to go to war with everyone. Plus, you know, the whole “killing millions of Jews” business, contrasted with Napoleon’s policy of pluralistic integration into society. You wouldn’t know that Napoleon’s problem was that everybody wanted to fight him, while Hitler’s problem was that he wanted to fight everyone.

Anyone with a basic knowledge of either figure would know this — but few people concern themselves with even elementary history. Popular perception matters, and the day may come when a future iteration of society happily nods along at an HBO-style series that treats historical Nazis as sympathetic heroes of a story from a bygone era whose troublesome aspects are downplayed. Think of HBO’s Rome — sure, Caesar is a ruthless general and a bit corrupt, but he’s also depicted as suave, clever, intelligent, and resourceful. His positive qualities are played up, while his morally objectionable actions are glossed over or omitted. Or HBO’s Vikings, which is committed to making Ragnar Lothbrok look like the coolest warrior-king that ever lived.

Nazi Germany certainly isn’t lacking the ingredients for glorification in the eye of the public; the “invincible Wehrmacht” myth is widely believed, as is the idea that Germany’s real problem was that their tanks were just so much better than everyone else’s. They conquered half of Europe in just a few years… you gotta respect that, right? Right?

That angle is the foot in the door for a laundered Third Reich. The final ingredient needed is the simple passage of time. This is not without precedent, either in popular culture or perception. The 2008 film Valkyrie starred Tom Cruise as colonel Claus von Stauffenberg, a German officer implicated in a plot to assassinate Hitler. He ends up executed by firing squad, and the dramatic lesson we are left with is that there were Germans who resisted, people who were merely patriots rather than fascists.

But Stauffenberg directly contributed to the Nazi war machine. He was an active participant. Defiance to Hitler and having a few principles certainly makes him less reprehensible than your Goebbelses or Görings, but he shares a direct moral accountability for one of the worst regimes in history. There were good people who resisted, like Oskar Schindler, but that resistance meant opposing everything the Nazi party stood for — not helping them win battles.

It’s easy to look at past carnage and shrug it off by saying that’s just how things were back then, and then focus on the dazzling uniforms, the fascinating military tactics, and the magnetic personalities of the “great men” who drove history forward. It’s easy to become detached, and to think that only a cold, dispassionate evaluation of history is worthwhile, because if we get bogged down grieving for billions of anonymous early graves, when do you stop? It’s easy, for anyone wishing to be seen as a “serious person”, to go along with the rigid convention of divorcing all emotion from the subject matter.

But any historical analysis worth a damn really does need a bit of emotion. Humans are not robots; we’re not indifferent logic machines. History is fundamentally a story — the story of humanity. To understand humanity and learn from its collective mistakes; to gain anything of true value from the enterprise beyond mere entertainment, we must include emotion. Without appreciating the human element of the Gallic Wars, or the Mongol conquests, or the Napoleonic wars, all we’re left with is a glamorized Hollywood re-imagining of history.

History has few heroes, and those that exist must be appreciated with a great deal of nuance. To understand history, we should consider not just the big picture, but the small picture as well — to register, on some level that isn’t just glossing past it, that every single soldier or civilian killed had a name, a family, and dreams of their own. That’s obvious, you may be thinking, but listening to the way so many people discuss history, one wonders. It’s worth taking a step back and rethinking the way we engage with history. History is the frame that explains the now, the sequence of events that led from A to Z, and it should be considered accordingly. By all means, enjoy pop culture. I do too. But don’t forget: the “great men of history” got to be great by stepping on people. Time may heal all wounds, but the lessons of some wounds are best remembered vividly.

See also: “Taking Heroes For Granted”

Subscribe now and never miss a new post. You can also support the work on Patreon. Please consider sharing this on your social networks. You can reach me at @AmericnDreaming on Twitter, or at AmericanDreaming08@Gmail.com.

“Liberal with libertarian leanings, Biden stan, neoliberal shill. Contributor at AmericanDreaming. I like philosophy, history and politics, just a random nerd who likes writing.” Total nonsense. Libertarian and contemporary liberalism are opposite political philosophies. Schill is a current term used by those who are poor at articulating their ignorant views. This article brings up an excellent point about how historical views can be diluted over time. It doesn’t espouse any political leanings. Learn, my friend, clear you head of those cobwebs.