US Elections are Quite Secure, Actually

Partisan hacks cry about voter fraud and voter suppression, but the data just keeps proving them wrong.

Jamie Paul here. This article is a guest post by James West, but I also wanted to share a recent piece I wrote in Queer Majority exploring the history — and historical revisionism — of queer witchcraft. You can read it here.

For a democracy to work, the vote must not only be legitimate, it must also be perceived to be legitimate, and in the United States, that perception is under attack. Democrats claim elections are rife with voter suppression while Republicans counter that the real problem is fraud. In both cases, each side has convinced themselves that any result they dislike is illegitimate. 60 years ago, they’d have been right — voter suppression and fraud really were a problem. John F. Kennedy once joked, “Don’t buy a single vote more than is necessary. I’ll be damned if I’m going to pay for a landslide.” JFK might have said that in jest, but many scholars believe he won the 1960 election as a result of the infamous Chicago machine and voter fraud in Texas. Voter suppression was also once commonplace, particularly in the South, which made blunt use of poll taxes, literacy tests, outright violent intimidation, and the rest. A series of laws were passed starting in the 1970s to address these problems. The question is, how much of a problem are voter suppression and fraud today?

Republican presidential candidate and former President Donald Trump continues to maintain that his loss in 2020 was the result of fraud, a claim that both his running mate and many Republican officeholders either tacitly or explicitly support. Faith in elections is central to a functioning democracy. Without mutual trust, the system ultimately collapses. But trust in government goes both ways — effective governments breed trust, and trust is essential to the effectiveness of governments. The specific fraud claims raised with regard to the 2020 election have all been found essentially without merit, including by Republican and Trump-appointed judges. What’s more, a great many high-quality studies examining both fraud and voter suppression in general have found that neither has an effect on modern elections.

Voter Suppression?

Starting around 2000, an increasing number of US states began passing laws requiring identification to vote. For nearly a quarter century, critics have alleged that this is a form of voter suppression. The argument is that not everyone has a driver’s license and the need to obtain one may discourage some from voting, even if they can get state IDs free of charge. Although voter ID laws have a legitimate use in deterring fraud, proponents of them, nearly all Republicans, often hurt their own case by explicitly saying they intend to use these laws to suppress the turnout of the poorest citizens (who vote heavily Democratic). Whether voter ID laws actually result in voter suppression has been extensively studied, and overwhelmingly, they’ve been found not to, with one very interesting caveat.

Studies have analyzed pre- and post-ID law turnout rates, along with other proxies, and found that the laws do not result in people voting less. This is also true if one considers turnout by race — in fact, voter ID laws may disproportionately suppress white turnout. This lack of effect is somewhat surprising: since voter ID laws increase the effort needed to vote, one would think turnout would be lower. One study suggests that the reason it doesn’t is because the effect is counteracted by Democratic Party get-out-the-vote efforts. The researchers found that in the absence of these efforts from Dems, voter ID laws would reduce voting by 2 percent — but with them, it’s actually increased. This means that, counterintuitively, voter ID laws may be actually bad for the Republican Party, because it impacts their voters as well and they don’t spend as much effort getting their voters registered as Dems.

Likewise, some voter suppression/turnout policies have had similarly paradoxical effects. For instance, early voting was supposed to increase turnout, but it actually suppresses the vote by around 2.5 percent. No one seems to know exactly why, but a possible explanation is that by spreading voting out, civic engagement is reduced: people figure they’ll vote later, they procrastinate, and then they run out of time. Blocking felons from voting actually increases voter turnout. One possibility is that the notices sent out to remind felons that they can’t vote mobilize other members of their households, although we can’t say for sure. Allowing election-day registration is one reform that clearly behaves as expected, increasing turnout by about 5 percent.

Polling locations are another controversial issue, with complaints of Southern states disenfranchising minorities by eliminating places for them to vote. The non-partisan National Bureau of Economic Research found that voters in entirely black neighborhoods did spend 29 percent longer in line than voters in entirely white neighborhoods, and were 74 percent more likely to spend more than 30 minutes in line. Even so, the median wait time in all-black neighborhoods was about 10 minutes. The researchers also found that the disparity between black and white voters was actually lower in Republican states than in Democratic states. Some of the worst disparities were in California, New York, Massachusetts, and DC, indicating that the wait-time disparity isn’t caused by partisan motivations, but rather high population density and urban congestion.

Then there’s the issue of voter registration purges. The goal of these purges is to eliminate what used to be a key method of fraud — keeping non-existent voters on the rolls to pad the vote. This is the basis of the old joke, “Grandpa voted Republican until the day he died, and then he started voting Democratic.” This sort of thing happened quite a bit in the first half of the 20th century, and reforms around voter registration lists were aimed at eliminating it. That said, it’s clear that “selective” purges have at least occasionally happened for expressly political purposes. To what extent are these selective purges a problem? A few studies have looked at the effects of well-publicized purges and suggest that they actually increase voter turnout. When people’s rights are perceived to be under threat, they become more valuable. For example, Florida’s 2012 purge of non-citizens from voting rolls increased overall turnout by 2.2 to 3 percent, and 2.5 to 4.8 percent among Hispanics. Other studies have found that purge errors are generally not partisan, but rather the result of a lack of state capacity, and have little effect on turnout.

What one person calls voter suppression, another calls protecting the integrity of the vote. That said, the data shows that neither the policies accused of being voter suppression nor those that aim to expand the vote generally have the intended outcomes. They either make no difference or have the opposite effect!

Voter Fraud?

Voter fraud, by contrast, is somewhat more difficult to study. After all, voter suppression necessarily happens in public, whereas fraud is hidden. However, there are at least three ways to study this. The first is anecdotal — for instance, in his 1992 memoir, Jimmy Carter describes Democratic Party rivals stuffing ballot boxes against him. The second is statistical — we can see places where the reported vote has extremely unlikely characteristics. For example, the 2009 vote totals in Iran, where it looked an awful lot like election officials routinely subtracted votes from Karroubi and added them to Ahmadinejad. Thirdly, we can look for any violation or weakening of the procedures designed to prevent fraud. It’s worth noting that every state and precinct in the US has multiple mechanisms in place to prevent fraud, from paper trails on votes, to both partisan and nonpartisan observers in vote counting, to systems that prevent ineligible and multiple votes.

Some kinds of fraud still happen, but they’re rare. One statistical estimate found that double voting fraud (where the same individual votes twice) occurs in roughly 1 in 4000 votes. Vastly more common (1 in 20 voters) was someone being erroneously registered in more than one district — but the overwhelming majority of these (99.5 percent) only voted in one. A 1 in 4000 rate alters the vote by 0.025 percent, which is not going to alter electoral outcomes except in extraordinarily close races. As an example, the 2021 Senate runoff election in Georgia, in which the candidates were separated by only 50,000 votes, is considered to have been an extremely close race. The number of likely double votes in that election based on this prior estimate would be 1,250.

Non-citizen voting may be substantially more common and problematic — and may have the capacity to change election outcomes. One rigorous analysis suggests that around 2 to 8 percent of non-citizens vote in US elections — most of whom probably being unaware that this isn’t allowed. The 1993 National Voter Registration Act enacts simultaneous voter registration and driver’s license issuance, which means many folks, including non-citizens, may find themselves automatically (and erroneously) registered to vote if they get their driver’s license. The fact that, unlike every other demographic group, non-citizen voting was higher among those with less education suggests that many of these voters may be unaware that they were not entitled to vote.

How much does this affect outcomes? A study that compared non-citizen votes to election outcomes found no relationship between the two — though establishing such a relationship would be difficult to ascertain. Non-citizens make up about 6 percent of the population, and if 2 to 8 percent of those voted, they would still sway the vote by 0.1 percent to 0.4 percent, which is likely below the threshold of statistical analysis, especially given that they are unlikely to all vote in the same direction.

As for dead people voting, a 2012 study looked for evidence in Georgia in 2006, and found that this type of election fraud probably didn’t occur. It’s a great joke, but it apparently doesn’t happen anymore, at least not at meaningful levels.

There is no literature on fraud around vote counting. Online queries for search terms like “lawsuits vote counting” bring up a fair number of cases, but they’re really around the interpretation of local election laws rather than outright fraud. Other cases don’t involve formal lawsuits but rather public accusations. For example, some Democrats accused Republican officials of fraud in Wisconsin after Trump’s surprise 2016 win, but the statistician Nate Silver credibly debunked the claim. The bottom line is that essentially none of the lawsuits or public accusations of vote counting fraud actually even allege fraud, and the few that have were refuted.

The last issue of concern is a practice known pejoratively as “ballot harvesting” or more neutrally as “ballot collection.” This is the practice of allowing third parties to collect and submit ballots for another voter. Ballot collection is allowed to at least some extent in 35 states. This is obviously a place where fraud would be very easy. In fact, a 2018 congressional election in North Carolina resulted in felony charges for multiple individuals and the results being thrown out. According to the North Carolina Board of Elections, the race was “corrupted by fraud, improprieties, and irregularities so pervasive that its results are tainted.” There were also complaints about voter intimidation in California in 2017 related to campaign workers making aggressive attempts to collect ballots. In the opinion of the LA Times editorial board, lax ballot collection laws not only allow for voter intimidation, but also raise the prospect of ballot collectors “losing” ballots on the way to drop them off, or paying voters to hand over unfilled mail ballots.

Overall, there are indeed places in the US where fraud is possible and happens, but so far, the scale is relatively limited, and it’s unlikely to affect elections overall, except when they are extraordinarily close. There are also processes, such as allowing outside parties to collect ballots, that seem ripe for fraud. These could probably use reforms, but they’re not a major problem. And yet, baseless claims of pervasive, nationwide voter fraud, and indeed the outright theft of presidential elections, have deranged the American political landscape.

Donald Trump and his close supporters made multiple allegations of fraud in connection with the 2020 presidential election. They claim that ballots were thrown away or altered, that the pattern of votes is statistically improbable (“ballots being added in the middle of the night”), and that fraudulent election procedures were followed (such as observers being excluded or ballot totals being tampered with). The American Bar Association has a complete list of litigation related to the election. The vast majority of these were found to be without merit — including by judges appointed by Trump. One of the main reasons to disbelieve all of the allegations of fraud is that they’ve been thoroughly checked by people who are strongly Republican. For example, William Barr, Trump’s Attorney General, said he’d seen no evidence of fraud on a scale needed to measurably impact the election. In addition, right-leaning publications like Forbes and the Wall Street Journal have published lists of these fraud allegations along with demonstrations that they’re untrue. The claims of fraud in the 2020 election were taken seriously, investigated, and determined to be unfounded — including by Republican investigators and judges.

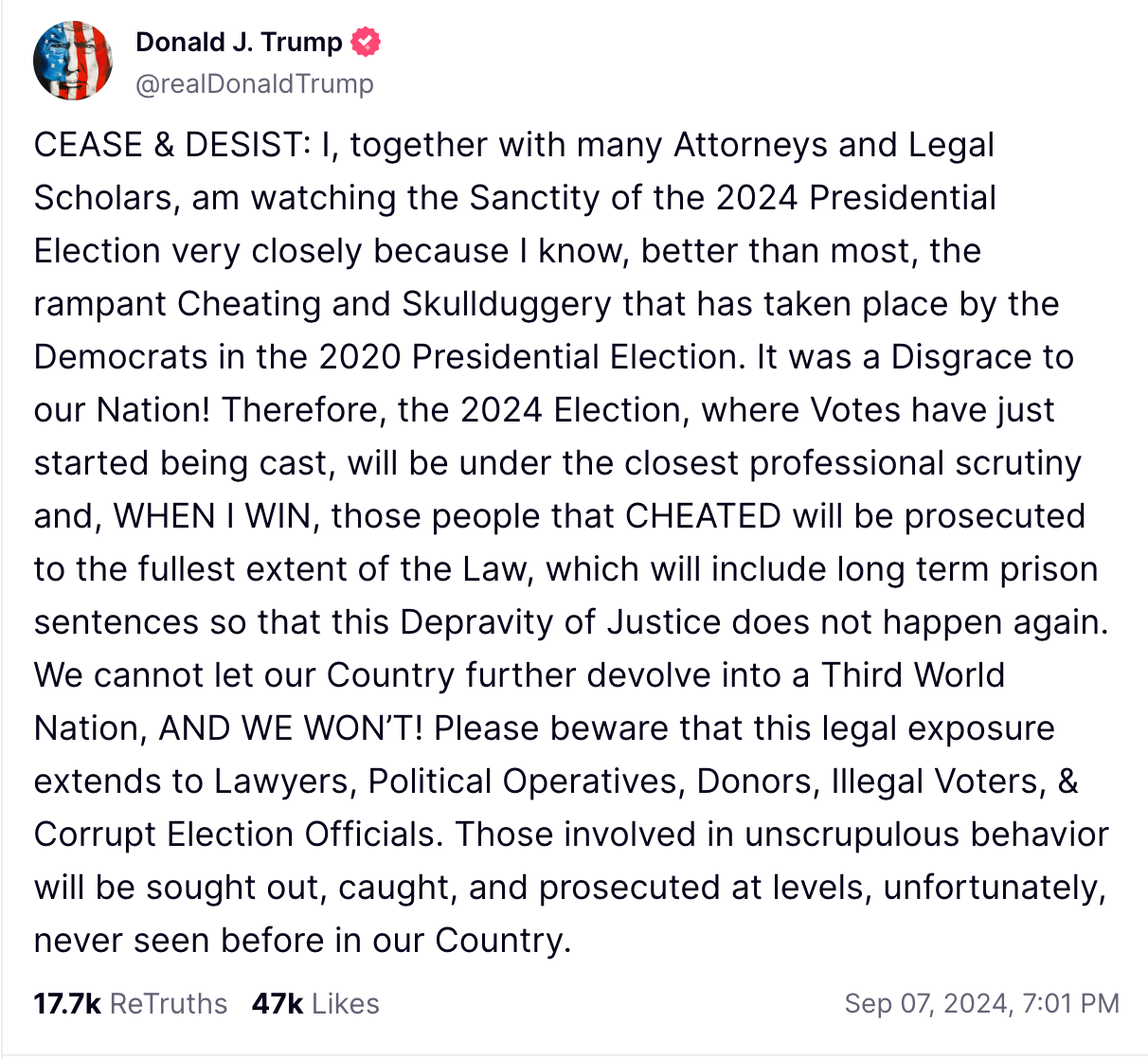

Unfortunately, Trump, his hardcore supporters, and some Democrats seem to be doubling down on stirring up voter distrust. Trump continues to not only explicitly claim that his loss in 2020 was the result of fraud, but that if he loses in 2024 it will be fraudulent. In fact, Trump will deny the election even if he wins, as he’s likely to lose the popular vote if he wins the electoral college, a fact he will almost certainly deny just as he did in 2016. Worse still, he’s stated that he plans to prosecute election officials if re-elected. This is part and parcel of the populist playbook, wherein populists intentionally undermine faith in institutions, including the democratic process, by claiming that they are rigged against the proverbial little guy. In so doing, they gin up anger and resentment for their own cause, but at the cost of weakening their own societies at home while legitimizing authoritarianism abroad.

On the other side, California Governor Gavin Newsom just passed a law that prevents local governments from requiring identification to vote. Both of these — playing on voters’ fears of fraud and voter suppression, respectively — decrease confidence in the validity of elections. Trust in the fairness of the electoral process is essential to the legitimacy of elected officials. If people don’t trust the elections, they won’t trust the intent of the government to act in the citizens’ best interests, making it impossible to govern.

In the ideal voting system, every eligible voter could easily register their vote with both a secret ballot and systems in place to minimize the possibility of fraud. A survey of the data shows that although we may not have reached that ideal, we’re actually pretty close. The levels of voter suppression and fraud are very low, to the extent that they exist at all. The state of our electoral apparatus is reasonably strong.

That said, there are still reforms or modifications that would move the US closer toward the ideal system. Most importantly, federal help in maintaining voter registration lists would be invaluable. A nationalized list would link social security numbers, voters, and precincts, preventing both double voting and non-citizen voting. Second, same-day registration would bypass many of these issues around disenfranchisement, particularly when coupled with a national voter registration list. Same-day registration would make it easy to verify that someone only votes once while also ensuring that they could vote where they live, even if they’d forgotten to notify election officials that they’d moved. Third, the US should simply end ballot collection/harvesting nationally. And finally, the government should enact strong ID requirements along with assistance for making sure voters have that ID. Overall, these changes would increase both the ease of voting and the security of the vote.

As important as it is for US institutions to do what they can to maximally safeguard both the security and legitimacy of elections, it is equally crucial for partisans on both sides to stop using false claims of suppression and fraud to motivate their bases. The US system isn’t flawless, but it works pretty well as is. Could it be better? Sure, nothing is ever perfect. But don’t let that undermine your confidence in the vote.

See also: “When More Democracy Is Less: The Paradox Of Primaries”

Subscribe now and never miss a new post. You can also support the work on Patreon. Please consider sharing this article on your social networks, and hit the like button so more people can discover it. You can reach me at @AmericnDreaming on Twitter, or at AmericanDreaming08@Gmail.com.