The Great Realignment That Wasn't

The parties aren’t realigning — you’re just spending too much time online (WARNING: Data)

We are living through a time of great social and political change. Societal tensions, tribalism, technology, income inequality, populism, conspiracism, and institutional distrust are deranging the political landscape and making hypocrites of everyone. Amid this turmoil, a narrative has emerged and caught on — that we’re going through a political realignment. According to this realignment narrative, the Republicans, formerly the party of business interests and the wealthy, are becoming the party of the working class and the proverbial little guy. Likewise, the Democrats, once the party of the downtrodden, are now said to represent the affluent professionals and powerful elites. So trendy is this notion that it’s become the consensus position in many political circles.

I set out to write this piece believing that we were, in fact, undergoing such a realignment, with the intention of exploring its causes and implications. Then I utilized an ancient technique from the before-times known as “research.” And the data, as I will demonstrate, does not bear the realignment narrative out.

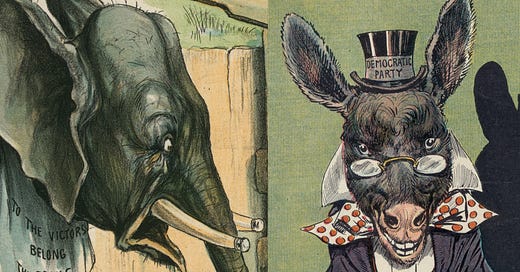

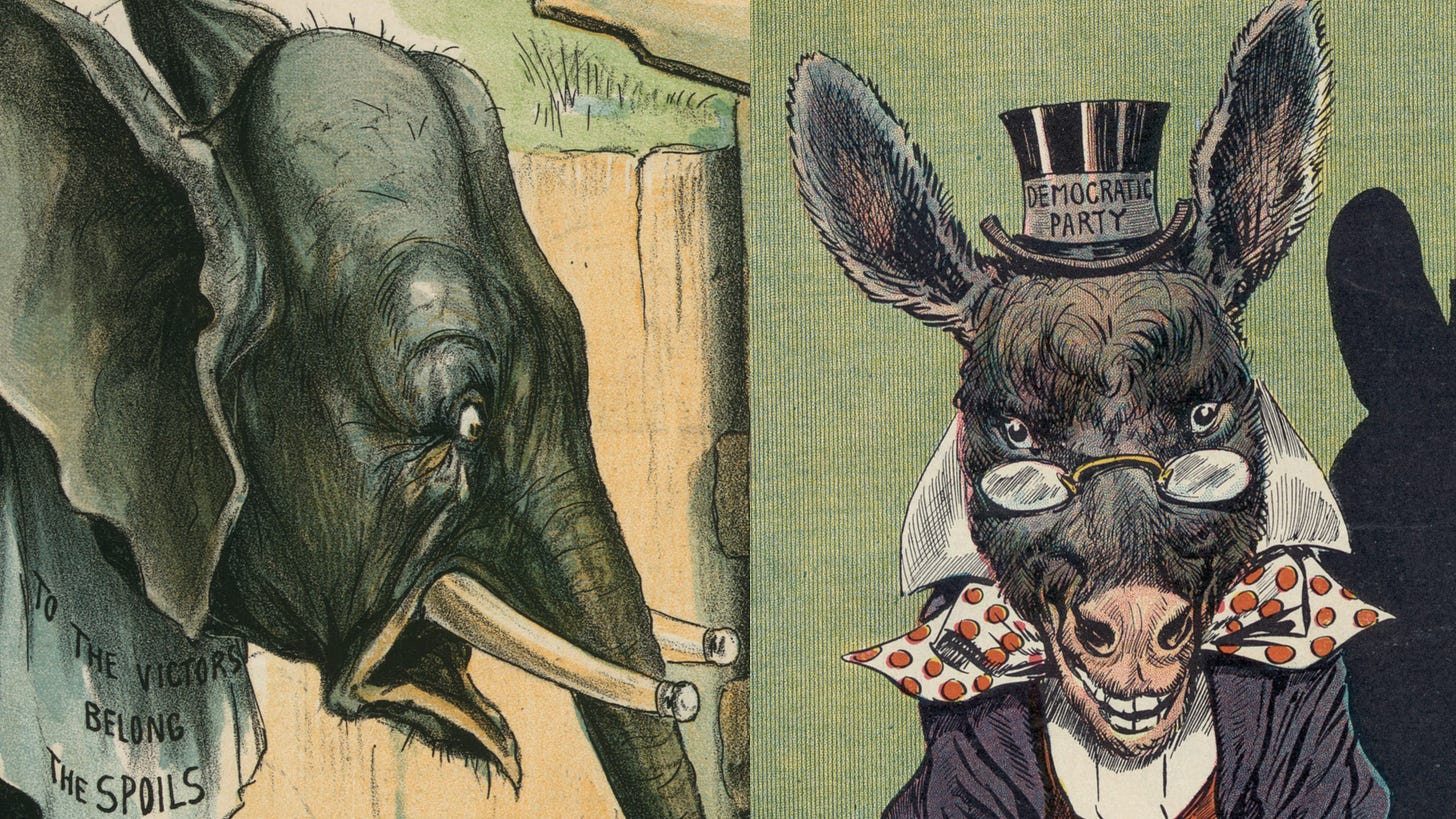

A Little Realignment History

For clarity, let’s first define “political realignment.” Encyclopedia.com does so succinctly, describing a political realignment as “A rare, significant, long-term change in the voting behavior and party identification of the electorate.” The Republican Party was founded in 1854, and soon became a liberal, mostly Northern, federalist, anti-slavery party. The Democratic Party, which had preexisted for nearly 20 years, was the more conservative, Southern, states’ rights, soft-on-slavery party. In the mid-1890s, a realignment occurred when Civil War issues faded from center stage and were replaced by new concerns, ushering in a political era where, to our modern sensibilities, Democrats and Republicans were not so easily differentiated. There were liberals, conservatives, progressives, populists, elitists, racists, reformers, social democrats, and libertarians on both sides.

The 1930s saw the next realignment, with FDR’s New Deal era changing the political landscape, moving the Dems left on economic issues and in a more federalist direction, and correspondingly pushing the GOP rightward and more states’ rights oriented. Even so, it was still common to see right-wing Democrats or progressive Republicans. In the mid-1960s through the early-70s, with the passage of the Civil Rights Act and changing attitudes about the Vietnam War, the most recent realignment took place, moving the Dems left on social and cultural issues, and dovish on foreign policy, while the GOP shifted to the right on domestic policy and hawkish on foreign policy. This realignment also ended, for the most part, the phenomenon of liberal Republicans and conservative Democrats, who have become increasingly uncommon in the decades since.

There are many inflection points around which a realignment might occur. This new realignment narrative hinges on socioeconomic status, and two subsets in particular: income/wealth and educational attainment. It is alleged that the Democrats are now the party of the well-educated and well-off, where they weren’t before, and that the Republicans are the party of the less-educated and worse-off, where they weren’t before. These are the two areas I will focus most on.

Which Data Should We Rely On?

The gold standard for gaining insight into what the electorate is thinking is political opinion polling, and specifically exit polling. Opinion polls are conducted at any given time, but exit polls catch voters immediately after they’ve cast their ballot. Exit polls do a better job of capturing voter opinion not as a snapshot in time, but as reflected in their actual votes, including last-minute deciders, as well as better separating voters from non-voters. This is the most direct way to gather information about the voting public.

The realignment narrative, however, relies heavily upon voter district data as its primary source of evidence. Every state is broken up into many voting districts, and district data looks at which side wins these various districts, and then analyzes them by their demographic and socioeconomic compositions. And by voter district data, we do see a shift. In 2008, Republican districts had a median household income of $55,000 per year, compared to $54,000 for Democratic districts. By 2017, red districts had declined to $53,000, while blue districts rose to $61,000. Measured by education, productivity, GDP per congressional seat, and share of professional jobs, we see a similar shift during this period, though in all of these latter categories, Dems were still ahead even in 2008.

The problem is, voter district data is a deeply flawed measurement, and far from definitive. It’s an indirect, messy way of trying to ascertain voting demographics. For one, a district is red or blue if one side gets 50.1 percent or more of the vote. Potentially, nearly half of the data about a given district can be coming from the losing side, and getting attributed to the winning side, since it’s “their” district. Many of the wealthiest GOP voters, like most wealthy people generally, tend to live in affluent urban and metropolitan areas, which are blue strongholds. Not only does the wealth and education of these Republicans get erased, it gets added to the Democratic ledger!

In addition, the fact that the parties periodically gerrymander the districts, redrawing the maps in creative ways to gain political advantage, can convey the illusion of a changing electorate when in fact we may simply be viewing different parts of it. Arguing the case that we’re undergoing a new realignment, and using voter district data as the primary or only evidence is tantamount to lying with statistics. And a broader look at the data exposes that lie.

The Educational Realignment Hypothesis

Exit Polling • General and Midterm Elections • 1982-2020 1

Education is broken down into the following categories. In recent cycles we have seen a shift in two of these cohorts. The others have remained steady.

“Less than high school.” This portion of the electorate has dwindled to the point that they are no longer polled separately, and are lumped in with high school graduates. The Democrats have carried this category for decades, sometimes by huge margins.

“High school or less” (includes prior category). HS grads went mostly blue until 2000, when they began to bounce back and forth between the parties, until 2014, where Republicans have carried them ever since.

“Some college” (sometimes including associates degree). Oscillated back and forth with the winds for 40 years, neither side gaining a lasting foothold.

Associates degree. Pollsters began counting them as their own category in 2014, and the GOP has won them in every cycle since.

Bachelor’s degree. Republicans won the majority of voters with four year degrees from the mid-80s until 2016 — the Dems have carried them in the three cycles since.

Postgraduate degree. The Democrats have absolutely dominated among postgrads for decades on end.

Opinion polling on voter identification by education maps closely onto the trends in exit polling, though slightly less pronounced in some areas. The bottom line: The two cohorts in which we have seen polling movement, “high school or less” and “bachelor’s degree”, make up about 53 percent of the country. This constitutes a definite shift on the educational axis.

The Income Realignment Hypothesis

Exit Polling • General and Midterm Elections • 1982-2020

There are five annual household income brackets measured by polling these days. Taking them in sequence:

Less than $30,000. The Democrats have been crushing it with the lowest income tier for decades, winning it every time it’s been measured for 30 years. Their lead shrunk in 2020 to eight points, still a significant margin.

$30-50,000. Bounced back and forth in the 80s and 90s, but the Dems have won it every election since 2000.

$50-100,000. The GOP won this group in most of the cycles since the early 80s, but Dems carried it in 2018 and 2020.

$100-200,000. 40 years of domination by the GOP, with the notable exception of 2016, where both parties tied.

Over $200,000. Republicans have won the wealthiest voters in every cycle for decades except 2016 and 2020, where the parties tied.

There hasn’t been much opinion polling done in recent years on voter income outside of exit polling and election season horse race coverage. The bottom line: There has been a little movement, but for the most part, things have stayed the same. Democrats continue to capture low-income voters with ease, and the parties tie in some of the higher brackets in elections where Donald Trump is on the ballot. Note that in the 2018 midterm elections, where Trump was not himself running, voting by income reverted quite cleanly to pre-Trump patterns. The data here does not even remotely suggest a realignment.

Wait a Minute…

You may be asking, as I did, how there can be a clear shift in the voting preference of certain education groups without a similar shift measured by income. It is well-established that educational attainment is linked with higher income, and so if there’s an education divide politically, basic logic dictates that there should be a corresponding income divide as well. What accounts for this incongruity is that different income and educational cohorts do not vote at similar rates. As Pew Research reports:

“Some of the largest differences between voters and nonvoters are seen on education and income. College graduates made up 39 percent of all voters in 2020 (about the same as in 2016) but only 17 percent of nonvoters. Adults with a high school education or less were 29 percent of all voters but half of nonvoters.”

The divide by income is even starker, with voters from households with annual incomes lower than $50,000 making up 48 percent and 38 percent of the electorate in 2016 and 2020, respectively, but 72 and 62 percent of non-voters. This means that not only are the poorest and least educated people less likely to vote, but that even within the category of “high school or less”, the wealthier one is — and there are many successful entrepreneurs and small business owners who never went to college — the more likely they are to vote. The end result is the partial decoupling of education and income, electorally.

Something Something, Non-College White Men

A lot of hullabaloo has been made over the voting habits of non-college-educated white men, who were one of the core constituencies that propelled Donald Trump to victory in 2016, and who have voted overwhelmingly Republican ever since. This subplot does not shed as much insight as one might initially think. As the country becomes more diverse and educated, non-college white men have shrunk as a share of the overall electorate, going from 63 percent in 1992, to 42 percent in 2020. Democrats have not won the white vote in any election cycle, midterm or general, since 1982. Dems have only won men twice since 1994, and not since 2008. The GOP has won white men in every cycle since 1984. And even though the Democrats used to perform well with voters who never attended college, majorities of non-college white men have identified as Republicans for the past 25 years.

Stop me when I’m supposed to be shocked here. This is like Lloyd Christmas walking past a framed newspaper clipping and exclaiming in astonishment “We’ve landed on the moon!” In what sense can the voting habits of non-college white men be indicative of a political realignment in the United States when it’s a mere continuation of the patterns we have seen for the past 30 years? Yes, they have become more pro-GOP than they were before, but they were already pro-GOP for decades. This is a difference only of degree, not of kind.

Perspective

Regardless of what the data says, it’s easy to get the impression that we’re living through a political realignment. And to be sure, while I’m arguing that this isn’t the case, I’m not arguing that things aren’t changing. Society is always in motion. And that’s truer now than ever. We have seen decades worth of cultural and social change crammed into the past eight years. Things that were kosher 30 seconds ago are now verboten, retroactive to the first self-replicating molecules in the primordial soup. In an era of political gridlock and inaction, politics has become an almost postmodern performance spectacle. Figures like Donald Trump, Marjorie Taylor Greene, Josh Hawley, Madison Cawthorn, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Cori Bush, and the rest of the “Squad” seem more like online influencers or reality television stars than they do politicians.

Certainly, our ideologies are also shifting. A conservative or progressive in 2022 is not what a conservative or progressive was in 2015, much less in 2010. But whatever it means to be a conservative or progressive today, they still overwhelmingly line up opposite one another with the same political parties their prior iterations did. 89 percent of people who identify as liberal continue to vote for the Democratic Party, as do 85 percent of those who identify as conservative for the Republican Party. Does that sound like a realignment to you?

Some commentators point to the fact that Democrats have become a do-nothing party that has forgotten about the working class. This isn’t the checkmate that realignment storytellers think it is. There’s some truth to it — but it’s been true for 30 years. Have you forgotten about Bill Clinton’s Reagan-lite Third Way centrism? Or Barack Obama, who governed indistinguishably from an 80s Republican? People marvel at how progressive a president Joe Biden has thus far been. That’s as much a commentary on the Democratic Party of recent decades as it is on Biden himself, whether observers realize it or not. If the Dems can be said, in any sense, to be the party of the rich, they have been the party of the rich for a generation, and the Republicans have been even more so. In reality, it’s not that the Democrats are the party of the wealthy, it’s that the poor have no party, because they vote less and can’t afford to donate.

What Explains the Shift, and the Perception of Realignment?

There has indeed been some movement in the voting habits of the electorate, measured by education. Unaccompanied by significant shifts on any other axis, this does not satisfy any reasonable criteria to be considered a realignment, and frankly, it’s not even close. But what has caused this shift? There are three main factors. First, decades of tepid economic policy from Democrats left some pockets of their base less enthusiastic than they used to be. Then, the advent of what Matthew Yglesias has dubbed the “Great Awokening” happened around 2013. It’s no coincidence that modern left-wing social justice politics, broadly denigrating of men, white people, and the uneducated, burst onto the scene a year before the GOP began consistently winning voters without university degrees, and two years before widening their lead with non-college white men.

And of course, the elephant in the room — Donald Trump. Trump made various segments of society feel heard more than any other politician in recent memory, and likewise repelled certain affluent elites with his lowbrow antics. This explains why, despite being the GOP’s home turf, the parties tied for support among some upper income tiers in 2016 and 2020 when Trump was on the ticket, but not in 2018, when he wasn’t.

Zooming Out

To anyone deeply plugged into politics, social media, and the culture wars, it feels like we’re living through some kind of profound realignment, because we see changes all around us, and we assume not only that what we see is real and representative, but that it maps onto every other kind of change anyone might allege. As is so often the case with social media, however, it offers only a keyhole perspective that leaves out most of what’s happening in society. It’s true that there’s been a leftward drift among some in the professional-managerial class over the past ten years. This cohort wields outsized influence in society. They are massively overrepresented in journalism, publishing, and institutions. They use social media as though it were their personal group chat. But when we look at the overall data, we see a different picture. Social media — it cannot be repeated enough — is not real life. As the kids say, “touch grass.”

See also: “The Great Realignment That Still Isn't Happening”

Exit polls: 1982-2010 • 1996 • 2000 • 2004 • 2006 • 2008 • 2010 • 2012 • 2014 • 2016 • 2018 • 2020

Subscribe now and never miss a new post. You can also support the work on Patreon. Please consider sharing this on your social networks. You can reach me at @AmericnDreaming on Twitter, or at AmericanDreaming08@Gmail.com.