The Great Realignment That Still Isn't Happening

Revisiting the evidence for the "political realignment" we hear so much about.

American Dreaming Contributor Timothy Wood has a new piece out in Queer Majority about the growing trend of gender-neutral awards: “There’s Nothing Inclusive About Gender-Neutral Awards.”

[Author’s note: some sections of this article make frequent reference to exit polling. Rather than littering the text with dozens of hyperlinks or citations, I have gathered 50 years’ worth of exit polling sources in a single footnote below. Other sources are hyperlinked as needed.]

In January 2022, I wrote an article debunking what might be called the realignment hypothesis — the increasingly popular notion that we’re living through a political realignment. Broadly defined, a political realignment is “A rare, significant, long-term change in the voting behavior and party identification of the electorate.” The realignment hypothesis asserts that the Republicans and the political right are becoming the working-class party, while the Democrats and the left are becoming the party of the affluent and the elite. When I reviewed the evidence, however, I found some minor shifts here and there, but no basis for the grandiose claims of a full-blown political realignment. It’s always possible for a hypothesis to be premature rather than false, though. Perhaps the signs of a realignment had yet to meaningfully manifest. With this in mind, I have revisited the realignment hypothesis to include the 2022 US midterm elections and the intervening 14 months of polling and survey data since my prior piece. This new information, as we will see, does not change my assessment: the evidence for a political realignment remains insufficient.

Trends Up Until 2020 — A Recap

The realignment hypothesis is a primarily class-based narrative. As such, the focus should center on indicators of class such as income and education. The question then becomes which data to rely on. As I covered previously, the most useful data for gaining insight into the electorate is exit polling:

“Opinion polls are conducted at any given time, but exit polls catch voters immediately after they’ve cast their ballot. Exit polls do a better job of capturing voter opinion not as a snapshot in time, but as reflected in their actual votes, including last-minute deciders, as well as better separating voters from non-voters. This is the most direct way to gather information about the voting public.”

When I examined exit polling from 1982–2020, including midterm elections, nothing on the income axis suggested a realignment. The Dems have won voters making less than $30,000 a year for 30 years, and voters making $30–50,000 for 20 years. The GOP mostly won the $50–100,000 cohort until 2018 and 2020 when the Dems won it. And voters making over $100,000 went Republican for 40 years, save only for 2016 and 2020 when the parties tied. Decades of blue domination among low-income voters is a rather inconvenient datapoint for those supposing that the Dems have lost the working class.

When I looked at education, the results were a little different. Voters who never attended college went mostly blue until 2000, then bounced back and forth between the parties for a while, but went red in 2014, 2016, 2018, and 2020. Similarly, Republicans used to win voters with a bachelor’s degree more often than not, but the Democrats carried them in 2016, 2018, and 2020. Every other category — “some college”, associate’s degrees, and postgrads — had not undergone any kind of shift. Still, there was enough movement here to conclude that something — not a realignment, but something — was going on. Taken as a whole, however, and along with other considerations, what began as an exploration of a phenomenon I assumed to be true became an exercise in refutation. I went where the data led me.

The 2022 Midterms

[Exit Polling • General and Midterm Elections • 1972-20221]

The 2022 midterms have yielded no new results. Democrats once again won voters making $30,000 or less, and those making $30–50,000. Republicans won voters making $50–100,000, $100–200,000, and more than $200,000. In education, Dems won 4-year degrees and postgrads, and the GOP carried people with no college, some college, and associate’s degrees. 92 percent of self-identified “liberals” voted blue (up from 89 percent in 2020), and 91% of self-identified “conservatives” voted red (up from 85 percent in 2020). While the 2022 data shows a continuation of shifting educational trends, on income and ideology, the electorate has moved even further away from realignment than two years ago.

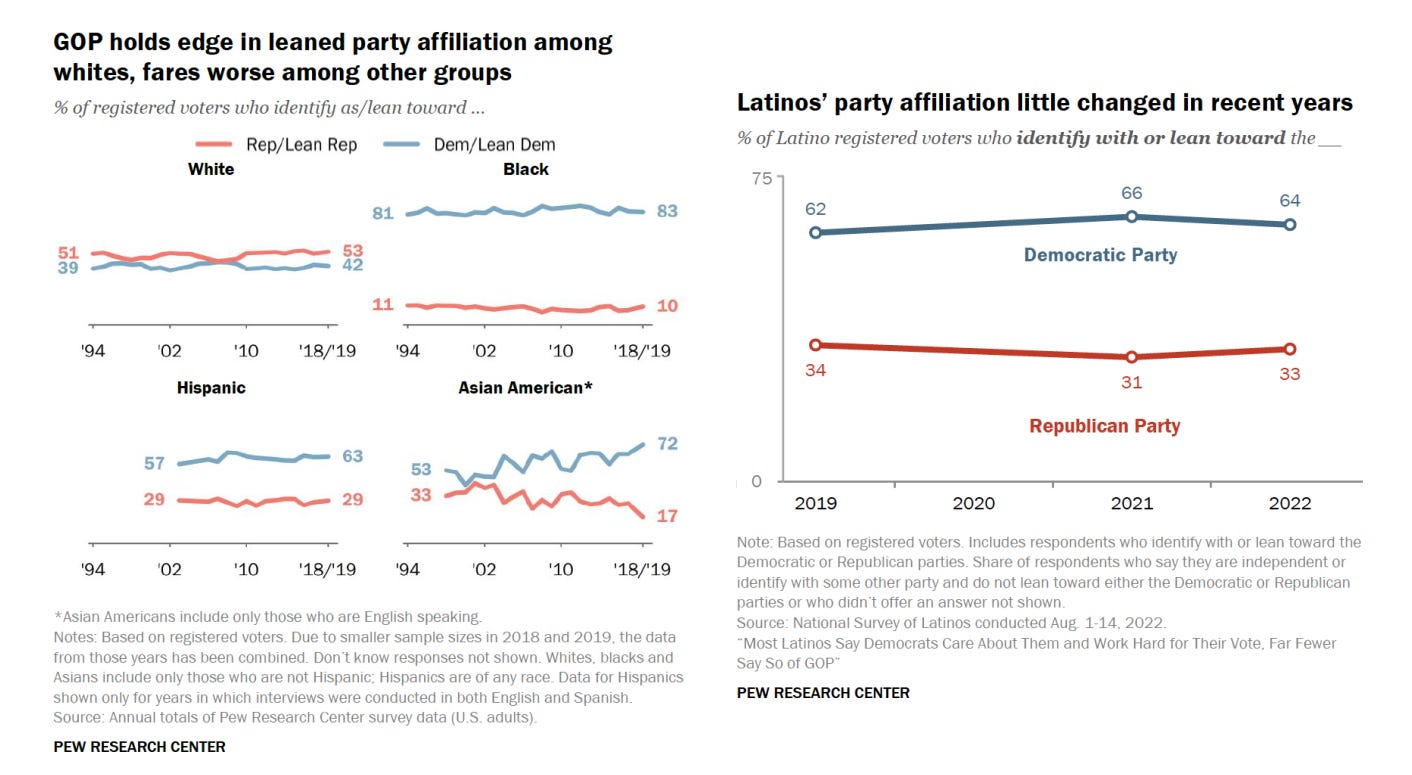

Race, Ethnicity, and Those Stubbornly Democratic Latinos

In addition to its claims of a socioeconomic realignment, the realignment hypothesis also alleges that racial and ethnic minorities are moving away from the Democratic Party. Except, that’s not what their voting records show. Exit polling going back to 1972 reveals an unbroken Democratic hegemony among black and Latino voters. Asian Americans, who have been included in polls since about 1990, have swung blue ever since 2000. This includes black, Latino, and Asian American men, wherever the polling breaks down race and ethnicity by sex.

Much has been made in the media of the Dems supposedly losing ground with non-white people. I get it — clickbait won’t write itself, and you have to fill the 24-hour news cycle with something. But the data just doesn’t bear this narrative out. We don’t even see significant trends in particular directions. The margins by which Dems win the various racial minority groups fluctuates up and down over time, sometimes increasing or decreasing for a few consecutive cycles, but then reversing. The closest thing we see to a shift away from the Dems is among Latino men. 63 percent voted blue in 2018, 59 percent in 2020, and 53 percent in 2022. Zooming out, however, this is not the first time we’ve seen this. Hispanic men saw an even steeper decline from 68 percent Dem in 2000 to 53 percent in 2004 before rebounding to 71 percent in 2006.

Expanding our search beyond exit polls and into surveys and opinion polling more generally, there was one datapoint that seemed to indicate some rightward movement among racial and ethnic minorities. Morning Consult showed that the number of black, Hispanic, and Asian Americans identifying as “liberal” decreased between 2017–2022, though the lion’s share of those people flocked to “moderate” or “don’t know” rather than “conservative.” That same poll showed dramatic increases in GOP support for nearly all demographic groups. As we now know, however, these findings, and the many others in the lead-up to the 2022 midterms that predicted a “red wave” never materialized at the ballot box. This goes back to the primacy of exit polling.

The rest of the opinion landscape seems to contradict the Morning Consult survey as well. According to Gallup, the percentage of black Democrats describing their political views as “liberal or very liberal” increased by 17 points from 1994 to 2022, and seven points between 2021–2022 alone. Hispanic Democrats increased by 18 points and five points on these same metrics over the same time span, respectively. Likewise, Pew and Gallup found that Latino party affiliation has changed little in recent years. Among Asian Americans, polling maps closely onto voting. Between 2020 and 2022, the Asian American Voter Survey shows no movement of Asian voters away from Democrats. Broken down by subgroup, only Vietnamese Americans identify as R more than D, and even then, only by plurality.

As with so many political terms, “realignment” can mean different things at different scales. Suppose the Democrats do, at some point, lose the Latino vote. In that case, we can say that there has been a realignment of the Latino vote; but absent other profound changes, it wouldn’t be a political realignment.

The Trump Effect

The Republicans have long been known as the party of the rich. They perform well with the highest income tiers and poorly with the lowest income tiers. This has been the case in just about every election cycle for as far back as pollsters have been measuring it. One thread the realignment narrative relies on is playing up the fact that in 2016, both parties tied among the $100–200,000 income cohort and in 2020 tied among both $100–200,000 and over $200,000. What explains this collapse of the Republican advantage among the wealthy but for the Democrats transitioning to supplant them as the party of the rich? Donald Trump.

As I noted in my earlier piece, the Democrats continue to win low-income voters with ease in election after election. Where the parties tie in some of the higher brackets is only where Donald Trump is personally on the ballot. This is why we saw voting by income return to pre-Trump patterns in the 2018 midterms, where Trump wasn’t running. Trump may resonate powerfully with certain disaffected segments of the population, but many of the elites the GOP usually win handily find his lowbrow style repellent. The results of the 2022 midterm elections only bolster this pattern, showing, once again, that when Donald Trump is not on the ballot, the upper-income tiers of the electorate revert to behaving as they long have, and vote Republican. This isn’t realignment, it’s an individual political figure turning certain parts of society on, and others off. Every rich person who usually votes GOP, but casts a ballot for the Dems in general elections where Trump is on the ticket, is doing so with a clothespin on their nose.

The Bottom Line

The bottom line is that there was insufficient evidence for the realignment hypothesis 14 months ago, and the data that has come out since has only weakened the case for realignment yet further. I searched far and wide, even delaying the publication of this piece in order to make sure I didn't overlook anything. Beyond what I have already included here and in my prior examination, I could not find robust evidence that either suggested realignment, demonstrated a shift in that direction, or even told us anything new.

Polls measuring party affiliation by political ideology show that the Democrats are moving to the left and the Republicans are moving to the right. This is a trend most people who believe in the realignment hypothesis also accept, never pausing to consider how fundamentally contradictory they are. We are seeing the traditional differences between the parties accentuate, not blur together or switch places. That’s the “re” in realignment.

The left half of society in general, and the Democratic Party in particular, are not losing the working-class vote nor winning the upper-class vote. Neither the political right nor the Republicans are winning racial or ethnic minorities. As the country becomes more racially diverse, the Dems win most of these new voters. Yes, there has been a shift among two of the five educational cohorts. And you can pinpoint specific districts, cities, or even states where various long-standing trends are bucked. At the national level, however, things are remarkably steady as she goes. To confuse those two is a category error.

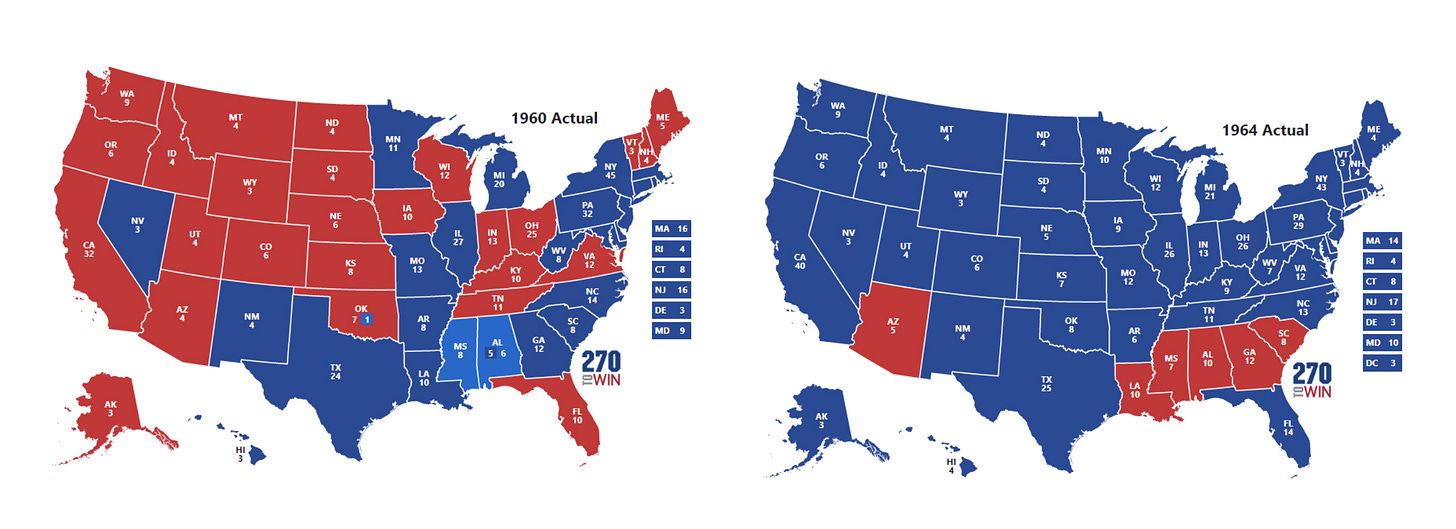

We have seen realignments before. In the 1890s, the 1930s, and the mid-1960s through the 70s. These past realignments were not subtle. They did not require careful parsing of certain fine-grained trends to tease them out. They showed up in profound and indisputable ways at the national level. The Deep South used to be a mainstay of the Democratic Party due to the support of many Southern white segregationist “Dixiecrats.” With the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Dems became the liberal social justice party, and the Dixiecrats switched affiliation en masse and never looked back. This is what the electoral map looked like in 1960. Then the Civil Rights Act passed months before the next election, and the 1964 map looked like this:

Whatever shifts are going on among certain segments of educated professionals, the white working class, Latino men, or Asians in big cities — inconsistent and often subtle shifts that you have to zoom in to the granular level to detect — do not belong in the same bucket as the above image. To lump them together under the rubric of “realignment” is to simply abuse the language.

Why People Are So Weirdly Invested In The Realignment Hypothesis

I understand the frustration many readers may be feeling. The arguments I have made and the data I have presented are missing the point, some may say. By reducing the real trends and phenomena we all see around us to voting habits and survey data, I will be accused of trying to gaslight people. The fundamental problem here is that we, as a society, are losing our ability to view things in perspective. Our hyperconnected attention culture is one that incentivizes the hyperbolic, the grandiose, and the superlative at every turn. We can no longer discuss societal changes or shifts — they must now be described as revolutions, uprisings, revolts, paradigm shifts, or realignments.

Nobody is denying that the world is changing, just as it always has. Despite the US insistently clinging to their own pet definition of “liberal” as a synonym for “left-leaning”, the American left has abandoned liberalism. Once the champions of free expression, self-described progressives now lead the charge to censor opponents and make the digital landscape “safe” from views that disagree with their own. So too, the right has abandoned classical liberalism in favor of populism and the mob politics of group resentment. Republicans have also jettisoned the muscular neoconservatism of yesteryear for the “America First” isolationism of the early 20th century.

Social media puts a magnifying lens and a megaphone in front of the most extreme. It’s easy to observe the political landscape today and conclude that it looks and feels very different from how it looked and felt a decade ago. That doesn’t mean we’re undergoing a political realignment. This cannot be stressed enough. What it means to be a conservative or a progressive is changing. There’s no doubt about that. But we’re not seeing self-described conservatives by the tens of millions becoming progressives, or vice versa. We’re not seeing once-reliable voting blocs changing parties wholesale. And we’re not seeing inversions of the electoral map. A recalibration is not a realignment. Evolution is not necessarily revolution.

There seems to be an element of the realignment hypothesis that goes beyond flawed analysis or dubious prognostication and transgresses into the realm of wishful thinking, not unlike the “red wave” discourse of 2022. Consuming the many books, essays, posts, podcasts, and conversations, it is difficult to shake the impression that those who propose a political realignment do not merely think it is so, but want it to be the case. It’s likewise hard not to notice that these, to give them a name, realignmenteers, are not drawn from a random cross-section of society. They are overwhelmingly people who feel disenchanted by the two party system; people who are non-woke; people unafraid to draw views from both sides; who abhor partisan tribalism and who tend to describe themselves with labels like “politically homeless.” The kinds of people who have, either in reality or in their own minds, not changed their political views much, but have observed politics shift around them in ways they don’t approve of. It would seem that someone like me should feel right at home in such a crowd.

At the same time, the realignmenteers also include many populists, many folks right-of-center, and many on the conspiratorial side. Being a classical liberal or non-woke moderate provides a powerful incentive to argue that you haven’t changed, everyone else has. To be sure, there is some truth in that, but we must recognize that it’s a hop, skip, and a jump from there to postulating an overall realignment, especially if you were formerly on one “side” and are now flirting with the other. “I didn’t change — they did.” The perfect justification for switching teams while maintaining that you haven’t switched values.

I initially assumed the realignment hypothesis was correct for the same reason most of its adherents do: it felt right. Then I researched it. Happily, I was never invested in the idea. I saw it as a simple truth proposition that, I thought, aligned with reality. Upon scrutiny, I realized it didn’t. But the reason why I revisited this subject is because I’m open to having my mind changed. You should be too.

See also: “Groucho Marxism and the Prison of Tribalism”

Subscribe now and never miss a new post. You can also support the work on Patreon. Please consider sharing this on your social networks. You can reach me at @AmericnDreaming on Twitter, or at AmericanDreaming08@Gmail.com.

I think it's fair to say that in the long term there could be some kind of realignment, but nothing super extreme. I don't think we can say for certain how things will shake out in the coming decades, especially given the populist forces you mention. I just finished reading Chris Stirewalt's Broken News and he put it really well that the ideal realignment would be liberals and conservatives recognizing that they have more in common than their progressive and nationalist populist brethren. That requires an overt decoupling from the supposed first principles espoused by the progressives and nationalists, which requires a shared agreement (lol sure that'll happen) that the progressives and nationalists don't get to dictate the conversation on things. My ideal vision is simply seeing four separate parties that aren't complete bitch-asses who have to try and capture the spirit of a mere two parties, but I'd settle for a realignment of the two existing ones toward something like liberal/conservative vs progressive/nationalist. The Democrats pretending to be super progressive and the Republicans pretending to be super nationalist has only made them both more detestable than they've ever been in my lifetime. They've become so obviously captured by authoritarian forces that most Americans have no interest in indulging.

Good points. I agree, the "realignment" is not happening as fast as people say it is. It is happening, but not at that 1960/1964 level. The anticapitalist conservatives like Sohrab Ahmari are not mainstream figures yet.