Affirmative Action May Have Always Spelled Trouble

Giving privileged treatment to select members of minority groups has led to some very dark places in history.

This post is by Contributor Alexander von Sternberg. He also has a new piece out in Queer Majority: “The Backlash Against Sexual Freedom and How To Fix It.”

Alex also recorded an expanded audio version of this essay on his History Impossible podcast.

In June 2023, a crippling blow was dealt to affirmative action, the policy that (originally) aimed to right the past wrongs of institutional discrimination against black Americans. In a 6-3 decision, the Supreme Court of the United States voted to block the use of affirmative action in the admission process of Harvard University and the University of North Carolina after being sued by the conservative group Students for Fair Admissions. How this ruling will ultimately shake out in future college admissions is anyone’s guess, but the precedent has been set: racial categories will no longer be valid indicators of one’s worthiness to be admitted to elite schools. Some see this as a rollback of decades of progress. Others are celebrating. The issue of race has long been one of America’s most polarizing, with views on affirmative action predominantly falling along clear ideological lines (with some exceptions, such as self-identified Marxist Freddie DeBoer).

This latest challenge to affirmative action was largely spearheaded by Asian American students who, despite surpassing every achievement criteria, had been unfairly denied admission to selective schools on the basis of race. There are, after all, a fixed number of spots in the top colleges. Positive discrimination on behalf of one group necessarily means negative discrimination against others, and Asian Americans, with the highest average test scores, faced the brunt of the latter. In fact, Asian students had to score 140 points higher than white students and 450 points higher than black students on the SATs to be considered in an equal light. This brings to mind the discriminatory practices employed by Harvard University (in part, under the direction of Franklin Roosevelt, no less) in the 1920s to limit the number of high-achieving Jews admitted. This precedent renders the outrage over race-based admission practices all the more understandable, but one need not know the history of “holistic admissions” to grasp why affirmative action had become both a self-parody and a target of legal proceedings.

David Malcolm Carson, a simultaneous critic and supporter of affirmative action, recently wrote, “When affirmative action was conceptualized, it was to right past wrongs. Then, it became sort of endless. It wasn’t just African Americans. It was Native Americans and Hispanics. And then it was women, LGBT, etc.” As a consequence of this expansion, it “wiped out the moral imperative […] because diversity is not quite as strong a claim as correcting past wrongs.”

Upon a closer examination of how affirmative action has been implemented as a means of correcting past wrongs, Malcolm Carson’s explanation begins to waver. One could argue that affirmative action’s expansion to include, for example, LGBT people, is also in service of righting past wrongs. But while there are cases such as Harvard University’s Secret Court of 1920, whose Soviet-style invasions of privacy resulted in the expulsion of eight students over homosexual activity, there is hardly a comparable history of systemic homophobia in higher education to rival that of anti-black racism.

The “righting past wrongs” narrative really starts to fall apart, however, when looking at the demographic most negatively impacted by affirmative action: Asian Americans. One must wonder if Harvard University’s Office for Diversity, Equity, Inclusion & Belonging has no historical awareness of, say, the 1871 Chinatown Massacre, the worst mass lynching in American history? What about the systemic abuse of the tens of thousands of Chinese immigrant workers during the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad? What about the anti-Chinese immigrant backlashes, pogroms, and the eventual passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which was not overturned until the Immigration Act of 1965 and its expansion in 1990? What about the internment of Japanese Americans into literal concentration camps during the Second World War? For that matter, what about the plethora of random attacks against Asian Americans during COVID-19? What happened to #StopAsianHate? If one was to apply the “righting past wrongs” standard, Asian Americans certainly warrant inclusion.

Of course, if the proponents of affirmative action were willing to say out loud that the many injustices faced by Asians “don’t matter” or are “not as important” as those suffered by generations of black Americans, then we would perhaps be able to have a proper debate. But that isn’t being stated. One need only read Justice Ketanji Brown-Jackson’s dissent in this Supreme Court ruling. In it, one sees the single-minded focus on the grievances of a single group, without regard to fair jurisprudence in the context of the Civil Rights Act, that is so characteristic of the most ardent affirmative action proponents. Many such supporters struggle to defend affirmative action without resorting to moralizing and faulty reasoning. Some are true believers, others have ulterior motives, but what unites nearly all affirmative action supporters of a certain socioeconomic set is self-interest. Having the “correct” views brings undeniable social and professional benefits. And, where institutions are concerned, sometimes financial benefits as well.

We must therefore ask: what’s happening in higher education? What are the top colleges up to when it comes to their affirmative action policies? If it’s not about righting past wrongs, then what? Some may argue that promoting diversity helps everyone — that diversity in and of itself is a strength. While it’s true that diverse groups tend to make better decisions, that has less to do with racial diversity on its own, and more to do with holistic diversity — the mosaic of thought, background, experiences, and, yes, identity, all interacting together. This makes it clear that the “diversity is a strength” claim is typically a superficial one. College admissions boards claim they want diversity, but as we see, they primarily use race as their barometer. This reveals that their motives are, quite literally, only skin deep — little more than public relations. Affirmative action has functioned not as a way to actually help black Americans close any gaps, but as a strategy to sell an image of institutional values.

Affirmative action holds the greatest value for those who matter most when it comes to higher education. It provides value for stakeholders (e.g. staff, community groups, industry, governments). It provides value for wealthy donors who may believe in affirmative action’s supposed goals, or who may just want to be seen as such. It provides value by attracting more applicants (whether of color or not). The more applicants there are, the more selective the school can appear, the more big donors and invested stakeholders there are, and the more the school can secure further funding from big donors and stakeholders. That’s the ugly truth about the elite college industry. These institutions seek what all corporate entities seek — better profit margins and unimpeded, perpetual growth, both in capital and in influence. That’s why the sausage is made the way it is.1

From the perspective of those running higher education institutions, everything relates to one thing: getting more money — from state governments, government agencies, private corporations, and bigger donors. The artificially deflated admission rates, the year-over-year increases in the number of donations, and the annual increases in both minority applicants and accepted students are all pursued in service of the almighty dollar, not any moral vision. Thus, affirmative action, at least in its current form, isn’t really about correcting anything; it’s about social and financial enrichment. In essence, affirmative action is positive PR for elite institutions.

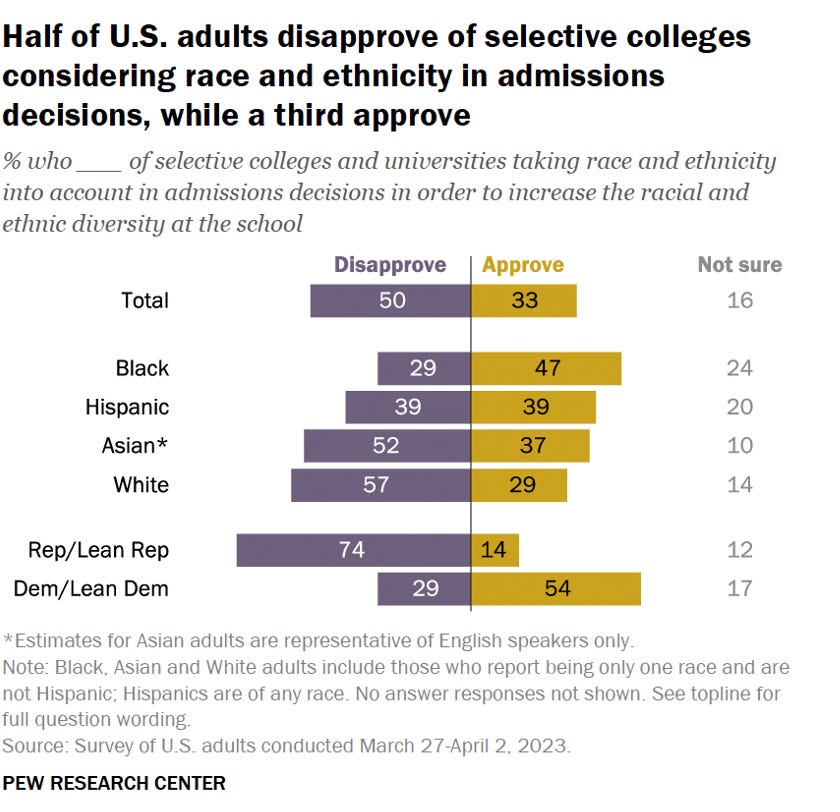

While recognizing the role that self-interest plays in these institutions, it’s unlikely that most critics of affirmative action see the issue through this lens. Most simply see it as unfair and increasingly obsessed with the past in a way that leaves plenty of other needy applicants out to dry. As of 2023, only a third of American adults approve of race-based affirmative action. In 2020, voters in California — hardly a bastion of white supremacy — soundly rejected Proposition 16, which sought to bring back race, sex, and ethnic considerations in public employment, contracting, and education. While polling should have little-to-no bearing on jurisprudence, this ruling on affirmative action seems to represent where social attitudes were heading anyway.

Some might argue that the public perception of affirmative action is incorrect. They might point to the fact that affirmative action does not constitute “racial quotas” (which were rendered unconstitutional in Regents of University of California v. Bakke in 1978) and that race merely plays a part in an overall measurement of an applicant’s admission. Be that as it may, perception often matters more than reality, especially in a free society. It’s clear that affirmative action is being perceived by many as a system in which certain people get special treatment while others do not, all by virtue of their group identity. Some will no doubt claim this view is nothing more than white supremacy at work (with its paradoxically multiracial character, as the writer Sheluyang Peng has amusingly pointed out). But looking at the world through a historical, big-picture lens, the popular rejection of affirmative action almost seems an autoimmune response against creating conditions that have already existed before.

Many proponents of affirmative action have framed it as a form of “progress”, implying that this is forging new ground for a multi-ethnic, multi-racial, pluralistic society. However, creating an elite institutional preference for a specific minority group, despite a relatively small number of its members actually benefiting from such preferences, has plenty of historical precedent, specifically in Europe. And that historical precedent, when examined, does not have a pleasant ending. When looking at European history, particularly in the post-medieval period, we see a very similar pattern: elites marginalize a group, and then begin singling out some of its members by virtue of their group status for special treatment. That is to say, the privileged treatment by European monarchs of small numbers of highly-skilled European Jews.

Consider the horrors that befell Europe’s Jews in the late 19th-to-mid-20th centuries. Those atrocities were motivated not just by naked prejudice and hatred, but also by resentment of the power Jews were perceived to possess as a group thanks to that privileged status a small number were granted by monarchs of old. It’s disturbingly easy, in light of this, to imagine a grim possible future for black Americans in the event that elite institutions — our own modern aristocracy — continue their preferential racial policies. History, of course, does not exactly repeat itself. But this is the logical endpoint of festering spite and resentment at scale, and it’s worth exploring a little deeper.

…

Throughout much of the diaspora’s history, European Jews faced a constantly uphill battle. The pogroms of the 14th century, spurred along by the Black Death and libelous claims made against Jews, are so well-known that the “poisoning the well” meme exists to this very day. The Jewish “blood libel” conspiracy theory maintained its relevance thanks to the chaos unleashed across Europe during that period of time.

Things didn’t get much better in the mid-16th century. Martin Luther, who had expressed relative warmth toward Jews earlier in his career, suddenly thundered vile invective upon them. In his 1543 treatise, On the Jews and Their Lies, he wrote that Jews were a “base, whoring people, that is, no people of God.” More disturbingly, he laid out what he believed should be done to remedy “this rejected and condemned people”, which included everything from “set[ting] fire to their synagogues or schools […] so that no man will ever again see a stone or cinder of them,” to taking “all their prayer books and Talmudic writings,” to “[abolishing] safe-conduct on the highways” so as to keep them properly ghettoized. These recommendations were ultimately made a reality, and the Jews of Europe were barred from holding onto any trade or lordship, something which Luther also referenced in his harangue.

This kind of attitude and treatment is the real reason Jewish people have been closely associated with very particular professions in the West: money lenders, and eventually bankers, lawyers, performers, and other types of artists. It had less to do with crude claims of facility with numbers or money or “natural talent” in the arts; those things have always been effects of early Jewish discrimination, not causes, despite what many anti-Semites would have you believe. This set Jews up for future resentments over which they were powerless. The “Court Jew” was a figure that arose out of need, thanks to the modernizing forces occurring in Europe at the time. As the philosopher Hannah Arendt explained in The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951):

“Beginning with the late 17th century, an unprecedented need arose for state credit and a new expansion of the state’s sphere of economic and business interest, while no group among the European populations was prepared to grant credit to the state or take an active part in the development of state business. It was only natural that the Jews, with their [then] age-old experience as moneylenders and their connections with European nobility — to whom they frequently owed local protection and for whom they used to handle financial matters — would be called upon for help; it was clearly in the interest of the new state business to grant the Jews certain privileges and to treat them as a separate group. Under no circumstances could the state afford to see them wholly assimilated into the rest of the population, which refused to credit the state, was reluctant to enter and to develop businesses owned by the state, and followed the routine pattern of private capitalistic enterprise.”

The Court Jews and the other highly-skilled Jews selected by European royalty — from Austria to France — were all fabulously successful, wealthy, and connected, but material conditions for most Jews living in Europe didn’t improve much. As Arendt noted, “[The Court Jews’] standard of living was much higher than that of the contemporary middle class, [and] their privileges in most cases were greater than those granted to the merchants.” However, this distinction managed to escape the people’s notice. The Court Jew was the birth of the modern anti-Semitic stereotype, the kind we hear from figures ranging from Henry Ford, to Bobby Fischer, to Nick Cannon, to Kanye West.

Because Jewish communities were effectively ghettoized, Court Jews came to be seen — both by the elite gentiles and the general public — as representatives of the Jewish community at large, when in fact they were anything but. Thanks to this, much of the public — largely ignorant of the vast majority of the ghettoized Jews who were a people apart — came to see all Jews as being associated with lucrative professions and heightened status. It’s important to keep in mind that none of this would have existed in the first place if European Jews hadn’t faced centuries of systemic discrimination. It’s the chicken-and-egg paradox that muddies the waters in the battle against anti-Semitism.

By the time many European states stepped up and did the right thing by providing emancipation to the Jews in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, it only managed to exacerbate the negative attitudes that already existed. As Hannah Arendt explains, “Emancipation meant equality and privileges; the destruction of the old Jewish community autonomy and the conscious preservation of the Jews as a separate group in society; the abolition of special restrictions and special rights, and the extension of such rights to a growing group of individuals.”

This is not to suggest emancipation was harmful or wrong by any means. It is simply to demonstrate that forces were already in motion whose momentum could not be stopped. There were downstream consequences of the decisions made by the elite and revolutionary classes of 18th and 19th century Europe. The situation facing Europe and its Jews became one where “equality of condition” was the premise but not the reality in which most Europeans found themselves living. Broken promises of equality gave way to class stratification. The only exception to the rule that individual status was defined by class were the Jews, who continued to be defined not only as an alien group, but by the perception of their elevated status.

Therefore, anyone engaging in class conflicts would be unable to unsee the different status of Jews outside the class hierarchy and thus make their own, typically flawed conclusions. When looking at these factors at play, it’s hard to imagine a scenario where the scapegoating of European Jewry would never occur. It’s not a coincidence that after emancipation occurred and Jews were perceived as having outsized privileges, a public ripe for populist convulsions turned to increasingly conspiratorial assumptions about them.

When the nefarious Protocols of the Elders of Zion forgery began its late 19th-early-20th century circulations, it was credulously eaten up across Europe and, eventually, the rest of the world. Concurrent with the pogroms that were rocking the decaying Russian Empire, the impression that Jews had more power than they actually did went global and remained so through Adolf Hitler’s Final Solution and to this very day. This warped and vile perception of Jews stems from the sloppy tokenization of European leaders and aristocrats eager to enrich themselves with Jewish skills, only made possible by the discrimination that put them in the position to cultivate those skills in the first place. The European elite may have been able to modernize their societies with Jewish assistance, but one could be forgiven for thinking that all they truly accomplished was reducing the diverse peoples of Europe to the categories of “Jew” and “gentile.” One could also be forgiven for seeing the racial reductionism of the contemporary United States as, to say the least, troubling.

…

In his fascinating book, The Loneliest Americans (2021), Jay Caspian Kang writes the following provocative statement: “There are still only two races in America: black and white. Everyone else is part of a demographic group headed in one direction or the other.” This refers first to the notion that immigrants to the United States, starting in the mid-19th century from places like Ireland, Italy, and the European Jewish diaspora, were all eventually granted “white” status. Second, and perhaps more controversially, it suggests that later immigrants to the United States — i.e. Asian and Latin Americans — just might achieve that supposedly coveted “white” status, despite not being identifiably white in any ethnic, ancestral, or self-conceived way.

Kang correctly points out how problematic this kind of characterization would be, especially for someone — say, a Chinese immigrant — who never saw themselves as nor wanted to be seen as “white” in the first place. And yet, the cracks forced open by the Supreme Court’s ruling on affirmative action, as well as the increase in rhetoric about “Latino white supremacy” and the supposed Asian American complicity in white supremacy, show that there is some perverse “truth” to this premise. Kang illuminates a mode of thought which, given sufficient runway, results in a worldview where the racial make-up of the US consists of parallel societies of “black” and “non-black” in a way that is eerily reminiscent of “gentiles” and “Jews.”

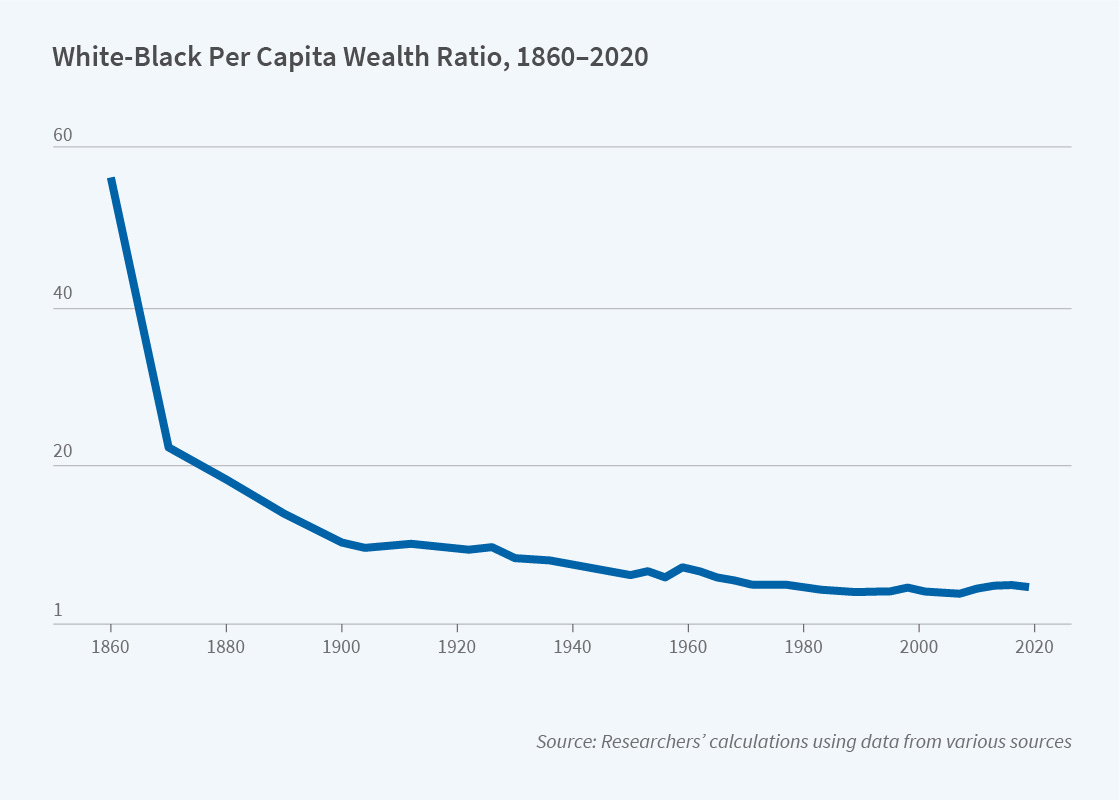

There are plenty of self-evident problems with looking at the world this way. For one, there may be a sense of “parallel societies” between “white” and “black” culture, but it’s all an illusion; black Americans are just as American — if not more in some cases — than many non-black Americans, if only in terms of cultural contributions and historical presence. While European Jews were forced by law to live in ghettos, that isn’t the case in the United States, especially in the 21st century. There are certain social and arguably systemic forces that create a similar effect with many black Americans, but upward mobility isn’t as confined as it once was, either for black Americans or for European Jews. And yet, as we’ve seen, there is an institutional force at work — that of self-enrichment — which seeks to use a certain sub-demographic of high-achieving black Americans for its own enrichment, just as European nobility also sought to use a certain sub-demographic of high-achieving Jews for their own.

The long-term effects of the latter scenario are well-documented. The long-term effects of the former have yet to materialize, and thanks to the legal rejection of affirmative action, they may never. The idea that what happened to European Jews could not happen again, to a completely different group of people with their own unique history tethered to their adopted country, is a dangerous bet against human nature whose wager is measured in human lives. We’ll likely never know, but it’s not a risk worth taking.

See also: “The True Darkness of Cancel Culture”

Subscribe now and never miss a new post. You can also support the work on Patreon. Please consider sharing this article on your social networks, and hit the like button so more people can discover it. You can reach me at @AmericnDreaming on Twitter, or at AmericanDreaming08@Gmail.com.

I speak from professional experience. As an undergrad, I worked for a large public university and raised over $100,000 in private donations. The amount mattered very little compared to the number of donations received. This is what management explicitly told us during training and quarterly briefings. They explained that these donations represented a “call to action” to the state legislature. In other words, an increased number of donors meant there was more reason for the state to further invest money into the university’s endowment.

Excellent! Nice close reasoning, really well-done.

Great post!