Don’t Fight Populism — Let It Fail on Its Own

The electorate chose populism. This time, they should get what they voted for.

One of the publications I work for, Queer Majority, has branched out onto Substack. It’s a cultural magazine exploring LGBT issues from a politically moderate perspective. They’ll be republishing select articles from the main site, including exclusive audio versions often read by the author, as well as future podcasts. You can check them out here.

President Donald Trump is back, and he’s been busy. Between staffing his administration, filling vacancies, issuing announcements, and signing a blizzard of wide-ranging executive orders, Trump 2.0 is off to a running start. The Democrats and their allies have been busy too — preparing to do everything in their power to jam a wrench into the gears of the MAGA agenda, just as they did during Trump’s first term. But doing so again would be a big mistake.

The US has been flirting with populism for more than 15 years. During that time, populist movements and leaders have come and gone and come again. Every time populism is beaten back, a few short years later, the electorate’s wandering eyes find it again. For those of us who reject populism, with its “us versus them” moral binaries, sweeping anti-institutional fervor, and rampant conspiracism, anti-intellectualism, and scapegoating, the impulse to #Resist it with every fiber of our being is strong, but misguided. We’ve gone down that road before, and it simply doesn’t work — not durably. To defeat American populism for the long term, it’s not enough to win an election only to cede power back one cycle later. The cycle must be broken. The blow that can set populism back decades isn’t one that can be dealt by any opponent. This time around, what Democrats and their institutional allies should resist isn’t populism, but their instinct to stymie it as they always do. For once, they should give populism the leeway to fail on its own.

Modern America’s off-and-on love affair with populism arose out of the failures of the George W. Bush-era War on Terror and the 2007–2008 Financial Crisis. It took shape first on the political right with the birther movement in 20081 and the Tea Party movement in 2009, and on the left with Occupy Wall Street and its dozens of spin-offs in 2011. As the 2000s became the 2010s, this populist energy fed upon the disgruntlement over deindustrialization, immigration, globalism, neoconservatism, and the gig-ification of the economy. It funneled into the candidacies of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders in the 2016 primaries and propelled Trump to victory. But the energy was given no release. It built, and built, and built, only to be bottled up.

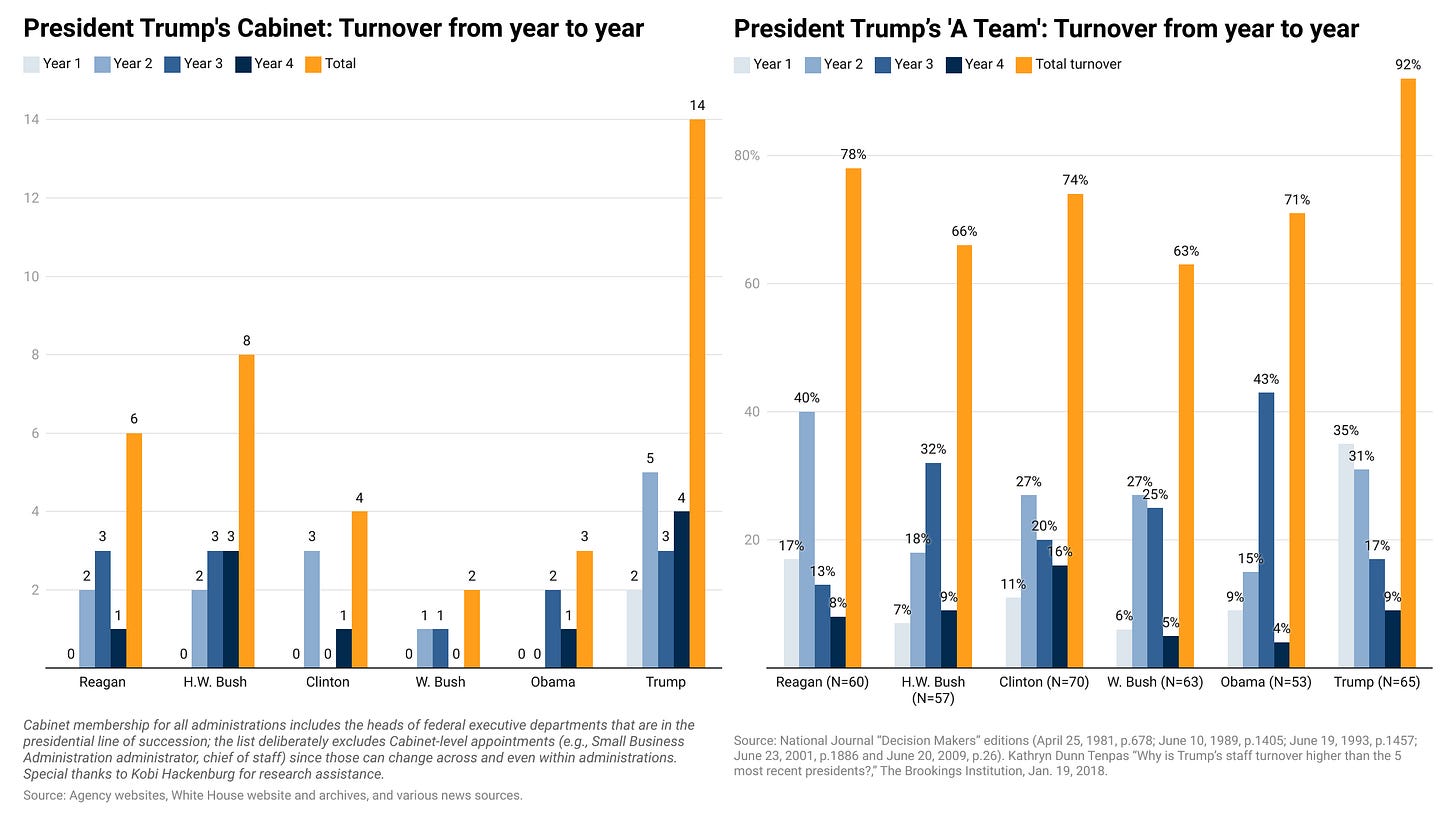

Trump’s first term in office was a masterclass in obstructionism and political sabotage by his opposition — including those in his own administration. Appointments were held up, bills were stalled or filibustered in Congress, and policies were met with a hail of legal challenges. Trump himself was blitzed with lawsuits, investigations, and two impeachments. And at every turn, a revolving door of advisors, aides, cabinet members, and White House staffers undermined Trump and continuously leaked to the press. Bogged down with constant internal scandals, the administration couldn’t generate any momentum and underwent the most staff turnover of any presidential term in decades.

This is not a moral judgment on whether any given lawsuit, resignation, leak, or act of insubordination was warranted. It’s simply to note that any president who faces such concerted resistance from virtually every direction, including their own inner circle, is going to have a very hard time doing much of anything. And, indeed, Trump got very little accomplished during his first term beyond a handful of items that wouldn’t have looked out of place on any generic Bush-era Republican’s résumé. There is nothing particularly “anti-establishment” about tax cuts for the rich, appointing religious conservatives to the Supreme Court, or facilitating relations between allies. Trump’s populist agenda never materialized. The border wall was not built, deportations didn’t increase, America’s foreign policy wasn’t dismantled, and the modest gains made in US manufacturing jobs were wiped out by the pandemic, whose response Trump bungled. By the spring of 2020, even far-right pundits like Ann Coulter, disgusted at Trump’s inability to enact any part of the MAGA agenda, dubbed him “the most disloyal actual retard that has ever set foot in the Oval Office.”

This all seemed like good news to Trump’s opponents and critics at the time. It certainly paid dividends in the form of Trump’s defeat in 2020, but the promise of populism was left unresolved, because it was systematically stifled and not allowed to manifest. The electorate never got to see the populist policies they voted for in action, and as a result, the infatuation with populism remained, paving the way for Trump’s historic comeback.

The obstructionist blue-balling of populism created a cycle made possible by the stagnancy of American politics. Riven by hyper-partisanship, money, bad incentives, and a bevy of inefficient but implacable, centuries-old procedures, mechanisms, and structures, the modern US political system breeds frustration and discontent as though by design. And that’s not likely to shift anytime soon. We are sadly no longer politically dynamic enough to make big changes. And so every time populism is hamstrung, smothered, and then defeated, its failures will largely come in the form of paralysis and gridlock, which populists can easily pin on their adversaries. Within this cycle, it’s usually never long before the chronically discontented public reaches for populism again.

Shackling populism’s hands may win a temporary reprieve, but not a lasting repudiation, as it only reinforces the narratives about “swamp” creatures, “elites”, and a nefarious “deep state” conniving to thwart The People. To break this cycle and end the infatuation, populism must be allowed to fully manifest. The American public needs to see how ugly, ineffective, and dysfunctional things can get under unfettered populist rule. Populism must be given the metaphorical rope to hang itself.

In practice, this means letting President Trump’s nominees and appointments sail through like they were coated in Clark W. Griswold’s industrial lubricant. It means not miring his every proposal in layers of legal challenges and institutional roadblocks, not tying his administration’s hands with a matrix of extraneous red rape, and not pulling every procedural trick in the book to slow, halt, or stall his policies. The electorate needs to see what Trump can actually do. If his anti-illegal immigration agenda morphs, as many of his supporters and associates wish, into a broader crusade against immigration altogether, that’s something voters need to see with their own eyes — progressive fear-mongering isn’t enough. If Trump’s tariffs and trade wars cause rampant inflation and economic problems, voters need to see that. If Trump’s policies translate directly into the application of extremism, bigotry, and wanton cruelty, voters need to see that.

If the past 15 years are any indication, the American electorate is unpersuaded by institutionalists sabotaging populism on the grounds that it would be too damaging for the country. Voters will keep casting ballots for populists in decisive numbers until populism is allowed to fail on its own.

Populists, even more than regular politicians, love to abdicate responsibility, but if their agenda is given the runway to spread its wings and resoundingly crashes, even their most brazen con artistry will be unable to convincingly shift the blame away from themselves. And if populism manages to achieve some tangible net-positives, that, too, is valuable information. My opposition to populism has never been deontological. I don’t think it is inherently evil. I see populism — by tapping into parts of the collective psyche, galvanizing particular elements in society, and cultivating a grievance ethos — as ill-suited to achieve necessary progress and much more likely to erode past progress. But neither I nor the most ardent populists have seen what American populism can do at the highest levels of power without its hands tied in ways that go above and beyond ordinary checks and balances. We are all, to one degree or another, speculating, at least in the US context. Maybe it’s time we found out how great or terrible populism truly is.

The movers and shakers in blue-team America see themselves as the champions of democracy. Now is their chance to prove it. The American people chose populism. Allow them to get what they voted for. And if, when push comes to shove, “democracy” is just a façade of cynically opportunistic branding, what about self interest?

America doesn’t like Democrats, beltway insiders, elite institutionalists, and everyone else who comprises the so-called “establishment.” Voters don’t see them as being any better than a populist clown show. The best case scenario for “establishment” types is to hold power every four years as the pendulum swings back and forth. If this new normal seems unacceptable, I pose a simple proposition to blue-team America. Which is the heavier lift: undertaking the deep soul-searching and complete psychological, cultural, and ideological self-reinvention needed to become likable, or stepping back and letting your opponents cement your status as the better choice?

See also: “Why I Am Not a Populist”

Subscribe now and never miss a new post. You can also support the work on Patreon. Please consider sharing this article on your social networks, and hit the like button so more people can discover it. You can reach me at @AmericnDreaming on Twitter, @jamie-paul.bsky.social on Bluesky, or at AmericanDreaming08@Gmail.com.

Interestingly, the question of whether Barack Obama was truly a natural-born American was first raised by angry Hillary Clinton supporters in the 2008 Democratic primaries. The political right then ran with it, with Donald Trump becoming the movement’s foremost cheerleader.

I see your point here, but there is a big risk with accelerationism. If we let Trump do whatever he wants unfettered, even if it successfully tanks populism's popularity for a generation, the damage that he causes isn't going to be easy to undo. So it's not like we can just let populism run wild for the next four years and then be done with it forever.

When do you think the "new populism" began? Palin and McCain?