How to Make Sense of the Trump News Cycle

With Trump's unprecedented blizzard of executive orders, a crash course in government can help parse the political stunts from the serious threats.

This article is a guest post by James West.

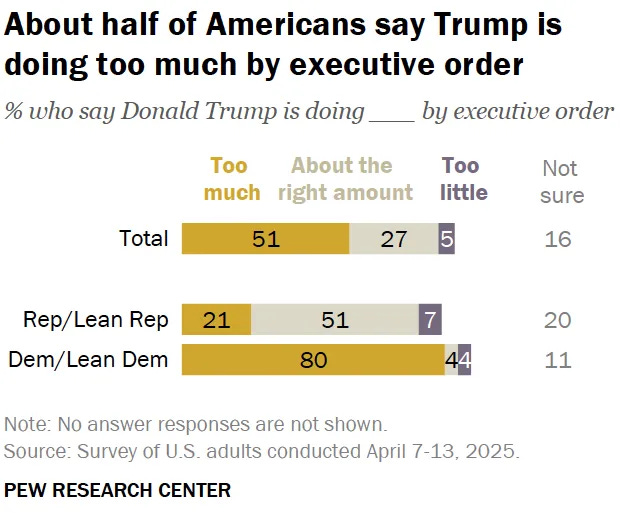

It’s been over three months since President Donald Trump took office in his second term. In that time, he has issued 139 executive orders; more than any prior administration’s yearly average since Franklin Delano Roosevelt. By any measure, both the pace and the scope of Trump’s executive actions are unprecedented. Beyond this, there is the constant stream of news about spending programs and federal employees that the new Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) is slashing, plus a slew of controversial immigration policies. The combined effect is enough to make it feel as though we’re living in a time of extraordinary change — that, whether one approves or not, there’s about to be a massive upheaval in the way the US government functions and interacts with citizens. However, better understanding how policymaking works, how the branches of government interact, and what is actual policy versus just rhetoric can help make the news cycle seem far less overwhelming and bring some needed clarity.

The most important thing to keep in mind is that the president can’t initiate new laws; they can only execute those passed by Congress. Similarly, a president cannot unilaterally restructure the government or allocate government funds. Presidents have some ability to create new programs, as long as they are within the executive branch, though there’s a fair amount of leeway in how that’s done. Still, we find ourself bombarded by presidential activity. There are several kinds of actions or statements that make the news — breaking them down by category will help make better sense of them.

1. Sound, Fury, and Hot Air

By far the largest category, both parties love this type of news because it feeds red meat to their base and requires no work. For example, after the US Supreme Court ruled in 2023 that the President couldn’t start a trillion-dollar spending program to cancel student loan debt by executive order, Joe Biden claimed that he was ignoring SCOTUS and forgiving the loans anyway, albeit in smaller amounts. This made Democratic partisans righteously happy, and Republicans righteously angry. Except Biden wasn’t really doing anything new or contrary to the law — there are countless existing programs for paying off student loans under various circumstances, and these were what he used. It had already been happening for decades, but nobody except the recipients paid attention. Trump’s first-term immigration policy was a similar situation. Democrats hated it and Republicans cheered, but it was simply a continuation of Obama’s immigration policy (in fact, fewer people were deported). And when Obama was president, Republicans hated his immigration policy and Democrats cheered.

This same dynamic is playing out now. For instance, when Trump says he’s going to use the military to enforce the border, that’s actually illegal (the Posse Comitatus Act). What has been done before and will likely happen now is the military assisting with road construction, blockade building, etc., along the border, which is perfectly legal — they just can’t perform law enforcement functions. Presidents want to be seen taking bold action, and this often entails making grandiose claims followed by doing more or less the same thing as their predecessors.

2. Policy Changes Within the Executive Branch’s Authority

Congress creates programs and sets rules for them, but in most cases, those rules are vague and open to broad interpretation, which gives the president more discretion to move money around than might seem constitutional. For example, Biden reallocated a substantial amount of science funding to DEI programs (diversity, equity, and inclusion) — over 10 percent of the National Science Foundation budget in 2024. For many scientists, this caused a massive headache, but it was within the president’s power.

The same thing is true across agencies. The president can direct the FBI or the DOJ or the Department of Education on their own priorities. In the case of USAID (United States Agency for International Development), Trump can’t actually abolish it, since it was created by Congress. However, he can reorganize USAID and spend the money on something else, so long as the spending is vaguely related to the legislation that originally enabled it. So too with tariffs: Congress gave the president essentially unilateral power to impose tariffs in the Trade Act of 1974. Anyone with an appropriate appreciation for checks and balances may justifiably bristle at Congress ceding all of this power to the president, but it’s legal — or at least, SCOTUS has historically upheld it.1

3. Policies That Are Legal in Principle, but Illegal in How They’re Carried Out

There are some circumstances in which a policy is legal, but if carried out improperly, will eventually be overturned — or, in some cases, immediately blocked — by the courts. Trump had a real problem with this in his first term. For instance, Obama’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program (DACA) arguably exceeded presidential authority (more on this later). But Trump’s attempt to end it in his first term was overturned by SCOTUS — not because ending DACA is illegal, but because the Trump White House failed to follow the Administrative Procedure Act in getting rid of it.

Similarly, SCOTUS struck down Trump’s first “Muslim travel ban”, not because the president can’t restrict travel from certain groups on national security grounds (Obama exercised this power, as did George W. Bush), but because Trump attempted to do so based clearly on religious animosity, which is not a legally valid reason. For those worried that SCOTUS is going to rubber stamp whatever insane or unconstitutional policies Trump tries to implement this term, the ideological makeup of the supreme court hasn’t changed since he was last in office. A fair amount of Trump’s current executive orders are likely to fall into this category. For example, Trump has taken actions to compel in-person work for federal employees, but many government agencies have collective bargaining agreements allowing remote work, which the president can’t unilaterally end.

4. Policies That Are Illegal/Unconstitutional, and Will Be Blocked or Struck Down

Trump’s executive order to end birthright citizenship is an example of policies that fall into this category: not only is birthright citizenship very explicit in the Constitution, there’s also congressional legislation making it explicit. As such, this executive order has already been blocked. Another is Trump’s targeting of major law firms to penalize them in retaliation for representing clients opposed to Trump, which the courts have blocked.

5. Policies That Are Illegal/Unconstitutional, But Will Not Be Stopped

The biggest recent examples of this category have been DACA, which was started under Obama and is still ongoing, and Biden’s decision not to enforce immigration law. Technically, presidential impoundment (refusing to carry out a law Congress has passed) is illegal, but while it’s easy to get a court order to stop government action, it’s much more difficult to get a court order to start government action. It’s possible that Trump is going to exploit this dynamic, since many of the changes he’s proposing fall into a “failure to do things” rather than starting new things. Plus, as previously noted, it’s relatively easy for the president to take congressionally allocated money and spend it on something else, so long as they can hand-wave that it’s the same thing. However, these maneuvers require subtlety and care in how they are executed, traits Trump has, well, historically struggled with.

6. Congressional Acts Actually Passed

This isn’t the executive branch, but it’s worth mentioning. As a practical matter, Republicans have a two seat majority in the House of Representatives, which is incredibly narrow, and their majority in the Senate can still be filibustered. Moreover, House Republicans are not a unified front — they’re a mixture of old-fashioned Chamber of Commerce Republicans, Libertarians, MAGA, the Christian right, and several Republicans from districts Harris won.

The bottom line is that for the next two years, Congress is very unlikely to pass any new legislation unless it has bipartisan support. Most of what happens on Capitol Hill will be Sound and Fury, with one big exception: budget reconciliation. Budget Reconciliation was established by the Congressional Budget Act of 1974, and once (and only once) per year allows passage of a budget-related bill without filibuster in the Senate, and with simplified rules in the House. Parts of the Affordable Care Act in 2010 were passed with budget reconciliation, as were the 2017 tax cuts under Trump’s first term. A bill passed through budget reconciliation can only be about the budget, and can’t include non-budget-related items. We can expect an extension of the expiring parts of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act this year, however, Congress could also use this to dramatically change budget allocations. They may not be able to end programs because they don’t have the votes, but, at least in the short term, slashing their budgets has the same effect.

***

This may all seem rather involved and in the weeds, but here’s the important part:

Most of the policies people pay attention to fall into categories 1 and 4 as outlined above. These are policies designed not to succeed in any procedural sense, but to outrage the opposition and delight the base. They are effectively PR stunts, but materially, they don’t change much. The domain in which most short-term changes occur is category 2 — because a president exercising their constitutional power over the executive branch cannot generally be legally stopped. The last area to pay close attention to is category 6, the budget.

Looming over everything is the fact that, without actual Congressional legislation, which Republicans don’t have the votes for, almost none of what Trump is doing will be permanent. And given the longstanding pattern of incumbent parties losing seats in midterm elections, plus Trump’s declining approval numbers, the GOP will probably lose the House in 2026. Already, many of Trump’s Executive Orders have been blocked by courts, and many others have litigation in process against them. Further, the Republican Congress itself doesn’t seem too keen on backing up many presidential actions. The Senate recently overwhelmingly turned down a bill to reduce USAID funding, and the proposed spending bills keep NIH funding intact or increase it. On the other hand, Trump’s many executive orders have been causing a lot of “creative destruction” — and the mayhem, confusion, and disarray is changing things, wholly apart from their legal or long-term impact. In some ways, the chaos itself seems to be a desired policy outcome — and there’s no legal basis required for that.

Ultimately, it’s too soon to tell what the actual policy changes of Trump’s second term even are, let alone what effect they will have. The US political system, for all its flaws, makes it difficult for the government or leaders to enact big changes — or to keep them enacted. To those in power, it’s a source of endless frustration. To the political opposition or worried onlookers, it provides some peace of mind.

See also: “US Elections are Quite Secure, Actually”

Subscribe now and never miss a new post. You can also support the work on Patreon. Please consider sharing this article on your social networks, and hit the like button so more people can discover it. You can reach me at @AmericnDreaming on Twitter, @jamie-paul.bsky.social on Bluesky, or at AmericanDreaming08@Gmail.com.

SCOTUS recently enabled some judicial pushback through ending the legal principle known as Chevron deference, whereby courts mostly deferred to federal agencies on how to interpret ambiguous or unclear statutes. In 2023, the Supreme Court overturned this doctrine.