This post is by Contributor Timothy Wood.

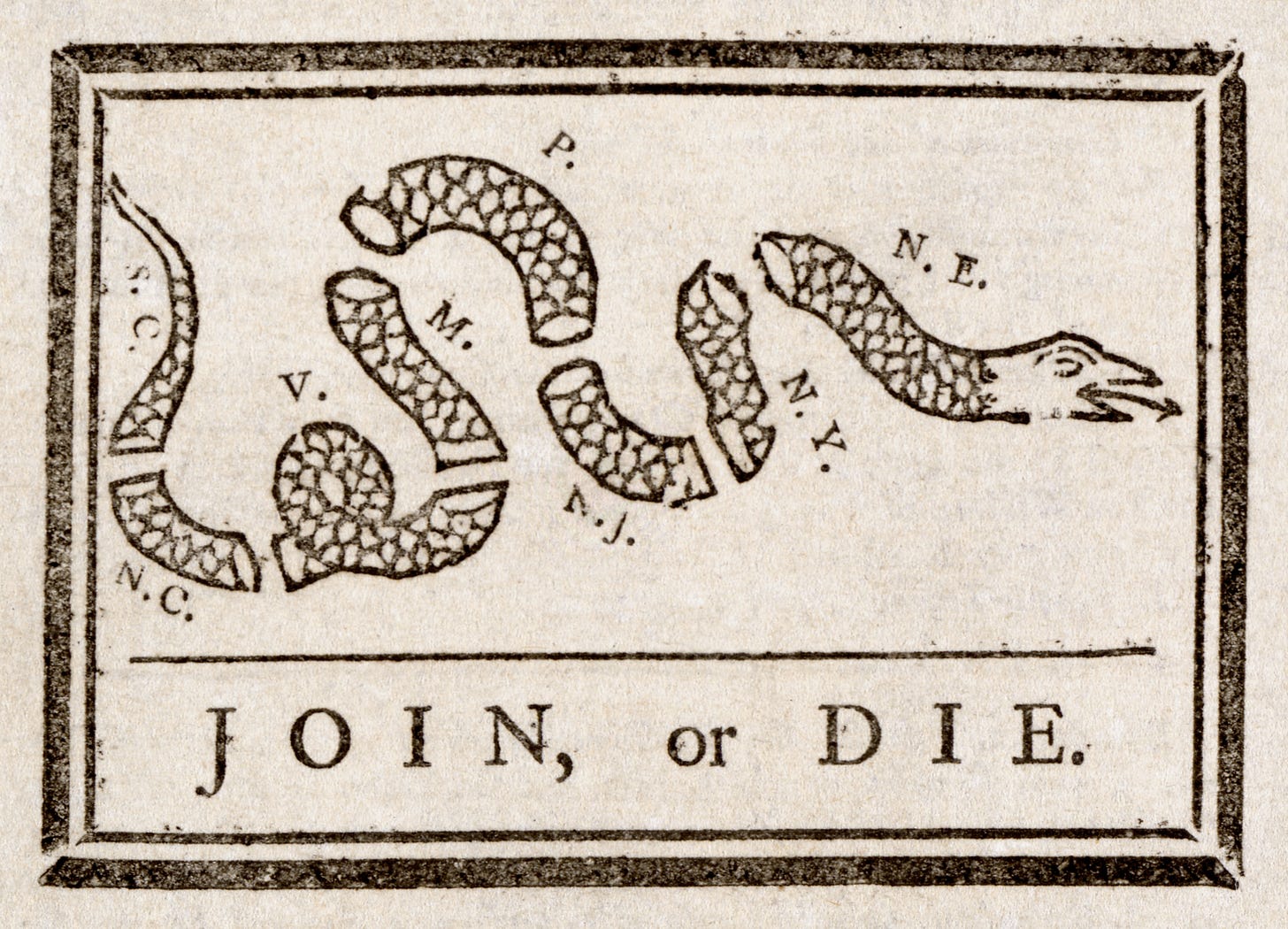

Americans are used to thinking of the Founding Fathers as enlightened thinkers espousing freedom. But just as with every set of hallowed values from the past, interpretations vary. We all have that neighbor who flies the Gadsden flag. It often seems to mean “Don’t tread on me in particular” and not “Don’t tread on anyone.” I prefer the other snake, the one from Ben Franklin that warns us to “Join, or die.” Getting along with others despite deep disagreements isn’t a suggestion; it’s an imperative. In the Founders’ era, this ethos of freedom and cooperation very much applied to religious differences. Today, when it feels like divisiveness is at an all-time high, it still does. The same rights that guarantee the freedom to practice one’s religion also guarantee others the freedom from religion. One cannot be protected without the other, and we forget that at our peril.

In the 18th century, the idea of religious freedom was pretty strange. Of course, at the time, the choices on offer in the West were Catholic, Protestant, or “other,” and the last one was mostly an afterthought. The idea of having a secular government was new. There were Catholic nations and Protestant ones, and they really liked to kill each other. The Thirty Years’ War alone depopulated as much as half the people in parts of Europe. That was only around 150 years prior to the American Revolution and was still very much a part of the cultural memory.

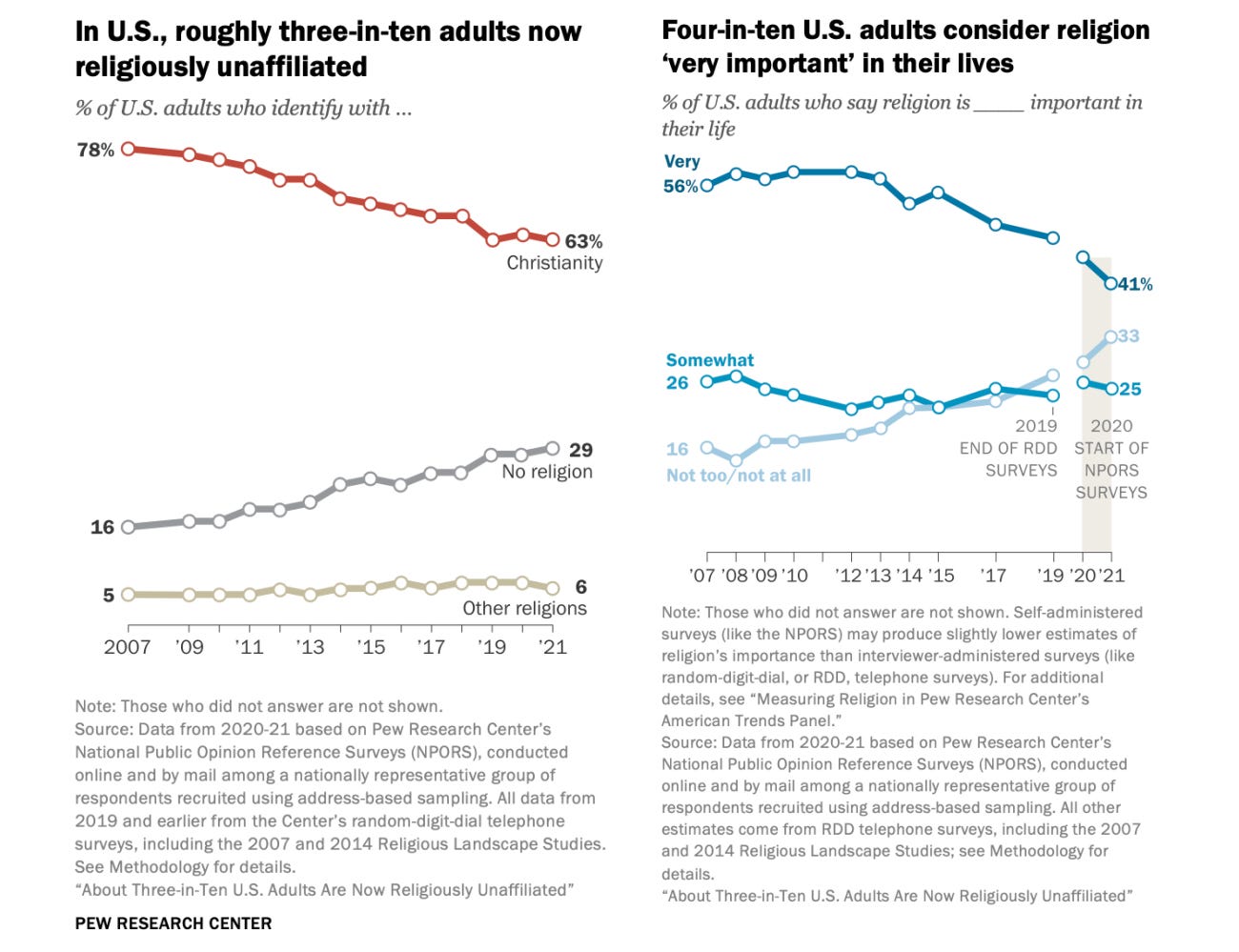

The idea of being an atheist was mostly disregarded, at least until France started to burn. Even the most irreligious of the Founders could only squeeze out vague deism.1 But it’s been two and a half centuries, and the non-religious are a thing. The “nones” — a catchall group that includes atheism, agnosticism, and anyone whose answer on religion surveys is “none” — have grown considerably over the years. Nearly 30 percent of US adults now say they are religiously unaffiliated, almost five times larger than all non-Christian religions combined. A significant portion of the remainder may be pulling their punches, given that less than half of Americans pray daily or belong to a religious congregation — and that includes 40 percent of those who identify as religious.

If you’re the kind of person who looks at the good parts from the Good Book and takes them seriously, more power to you. My wife and I also value those as guiding principles of moral philosophy. There is wisdom to be found in nearly every religious tradition. Muhammad didn’t need to mention that people should care for orphans, but he did. That’s a good principle. In what today seems like an alternate universe, during the Islamic Golden Age, Islam enforced a legal system of religious toleration that, while deeply flawed, was an improvement over the status quo. So lest we lose track of it, toleration is very much a historical pendulum, and by no means inevitable and permanent.

But in the history of religious freedom in the US, it was mostly Christians all the way down, and the main concern was that these different denominations of Christians please stop killing one another. In 1771, an Anglican sheriff in Virginia dragged a Baptist minister from his pulpit into the streets, and whipped him. Not in the Southern sense of “whooped”, as in spanking an unruly child, but actually beat him with a whip. New York State’s constitution in 1777 banned Catholics from holding public office. Many European immigrants to the US were fleeing religious persecution, up to and including public disembowelment in the case of Jesuits. Back in pre-Enlightenment Europe, if killing a leader wasn’t sufficient, folks asked “why not just kill them all?” That’s not even getting into the people Christendom really hated. Spoiler alert: being a Jew may be hazardous to your health. Anti-Semitism is as time-honored a European pastime as kicking a ball or fighting with the Germans.

Even post-Civil War, the US persecuted the Mormons to the point that they founded their city next to a lake of undrinkable water, because that was the only place they could be left alone. Their crime was mostly polygamy, because somewhere along the way we forgot that Sarah told Abraham to go schtup their slave (Genesis 16). Honestly, it’s a little bizarre that if you’re into it, I can keep you locked in a box in my basement clad in a distasteful amount of leather, but we can’t enter into a consensual legal agreement of marriage if there’s more than two of us? “Don’t tread on me”, unless of course being tread on is your kink, in which case you can totally do it, but we’ll send you to jail if more than two of you try to get married and file taxes together.

I can sympathize with the Mormons, because, as an atheist, a lot of folks apparently don't like me either. Atheists have long been among the most distrusted groups in the US. 40 percent of the electorate are unwilling to vote for a well-qualified candidate if they are an atheist. As recently as 2011, Americans expressed such a distrust of atheists that of all the categories of people researchers surveyed them on, only rapists were distrusted to a similar degree. Those numbers have improved in the years since, but 40 percent of Evangelicals still feel non-religious people are less trustworthy, which would be an astonishing number if applied to any other group.

We happily publish stories in major outlets with headlines like “Atheists Fucking Suck.” Just imagine Vice publishing “Jews Fucking Suck” or “Muslims Fucking Suck.” It may well be the last thing they ever published. The non-religious are routinely vilified as “immoral and un-American” when our only crime is not doing anything. Our main gripe is with folks trying to foist their beliefs on others, because the right to tread isn’t an acceptable exercise of your religious freedoms.

What do I tell my coworkers about my beliefs? I don’t. In many parts of the country, that can be a social death sentence. There’s a term the non-religious community has borrowed from LGBT folks: coming out, because, like the stigma around being LGBT, it’s often better to be quietly neutral than to be honest. By some estimates, between 16 and 23 percent of American atheists may still be in the closet. Again, we need only apply this to other groups to see the problem. If one Jew in five were afraid to self-identify in public, that would be considered a social disaster.

We have to stand together for the freedom of and from religion or, let’s be honest, I’m in trouble. If you're a believer, I care about your liberty, because if you’re in trouble, then I’m boned. Thomas Paine once wrote that anyone seeking liberty for themselves must guard even their enemy from oppression, otherwise it “establishes a precedent” that will eventually be applied to themselves. Don’t tread on one another. Unite or die. I will join to protect your church, mosque, synagogue, or temple. In return, afford me the right to live my life. I don’t want your children to be ashamed to say they pray or attend service. I don’t want my daughter to be ashamed if she doesn’t. If we are to be a free society, that’s a line we have to hold. If a fundamental right isn’t universal, then it isn’t a right. If freedom only works in one direction, then we aren’t free.

See also: “Believers, Atheists, and the Unexamined Life”

Subscribe now and never miss a new post. You can also support the work on Patreon. Please consider sharing this article on your social networks, and hit the like button so more people can discover it. You can reach me at @AmericnDreaming on Twitter, or at AmericanDreaming08@Gmail.com.

I’ll give them some credit. Thomas Jefferson published his own Bible, taking an actual razor and literally cutting out all claims to the supernatural. Thomas Paine published The Age of Reason; Being an Investigation of True and Fabulous Theology (1794), which doesn’t argue theology proper, only that the Bible is internally inconsistent. Still, mad props to a guy who apprenticed to make corsets and somehow became a political philosopher.

Another term I’d personally like to borrow from the LGBT community is allyship. The challenge I have as an atheist, around particularly devout Muslim family members, is they don’t have an interest in being an ally.

To be American is to accept the primacy of mutual tolerance over any contrary directives of one's own religion - such as stoning adulterers or subjugating unbelievers - and so in a strict sense, no true American can be a true follower of any religion including such directives (most). All genuine Americans put the Constitution above any particular holy book - in this way it is really a sort of Unitarian framework, having the mere flavor of any given old-world religion an American chooses to practice.