Longshots and the Power of Dreaming Big

I'm not in Zach Graumann's recent book, "Longshot," but it was my story too.

Zach Graumann is a name you’ve probably never heard. He quit a lucrative job on Wall Street in 2017, at age 29, to manage the presidential campaign of some dude with no political experience, no name recognition, and no resources. The campaign was nearly broke, and its headquarters was in an apartment leased to the candidate’s mother, where the only other staffer had been crashing. Their mailing list was the candidate’s personal Gmail contacts. The signature policy proposal was giving everyone in the country $1,000 a month. 1,212 people ran for president in 2020. By all rights, Andrew Yang should have been one of the 1,190 people you’ve never heard of. No oddsmaker would ever have bet on Andrew Yang, universal basic income, and the Forward Party becoming known entities in society. The fact that they are is because of Zach Graumann, whose recent book, Longshot: How Political Nobodies Took Andrew Yang National — and the New Playbook That Let Us Build a Movement (2022), tells that story.

Longshot hit home with me. Hard. For over a year in the late 2010s, I was a full-blown political activist — something I’d never been before, and may never be again. My time as an activist forever changed the way I understand politics. Longshot wonderfully captures the emotional rollercoaster, inner tensions, and contradictions inherent to activism and politics more broadly. Reading it felt as though I was watching one vignette of a Rashomon-like film from the perspective of another vignette’s protagonist, because in a sense, it was about me, too. It might not have been told from my specific vantage point, but I was there, watching and participating in real-time as everything in the narrative unfolded.

I first heard about universal basic income around 2013, and unlike most people, who need a bit of convincing, it made perfect sense immediately. Eradicating poverty, reducing bureaucratic waste, and building a universal floor struck me as an unalloyed good that would pay for itself and then some. But it was a podcast idea. A Ted Talk Idea. A niche idea too smart to ever be mainstream. I never expected it to enter the Overton window. I never expected it to become popular. I never expected a presidential candidate to credibly run on it.

I was intrigued when a guest on Sam Harris’s podcast in June 2018 talked about how he was running for president on UBI, but I thought little of it. It was enough to get me to buy and read his book, but not enough to take his campaign seriously. Yang was obviously running merely to advance an idea and start a conversation, and while I wished him the best, the prospect of him even achieving that much seemed remote. As an actual candidate, Yang was as absurd to me as Vermin Supreme or Jimmy “The Rent is Too Damn High!” McMillan.

But Yang’s low-budget campaign ads from December of that year were enough to persuade me that he was, in fact, running for president, and not simply doing a book tour. However infinitesimal his chances of winning, that demonstration of effort and intent somehow made the project real. I found myself following the campaign with real interest. When Yang’s Joe Rogan interview went viral and his popularity began to take off, there was an energy in the air. And when the Democratic National Committee announced new qualification thresholds for the debates that were well within Yang’s reach, I allowed myself to dream.

It’s still difficult to believe that I became a political activist. I’ve never been the kind of person to join things, or wear labels, or become a cog in a larger machine. I’ve always been ungroupish, independent, unaffiliated, and as difficult to herd as a cat. I didn’t do parties, tribes, or movements. But the Yang 2020 campaign inspired me in a way no political cause ever had. The message, the man, and the excitement around him made me a believer. I relaxed my self-consciousness, my aversion to movements, and, yes, some of my principles. By slating my state, New Jersey, among the last to hold their primary elections, at which point the race would long since have been decided, the Democratic Party told me that my vote didn’t count. So I was going to make sure that I had as outsized an influence as I could. That would be my vote. I’ve come to playfully regard myself as a Groucho Marxist — someone who avoids tribalism and sees only downsides to joining groups. But some things are worth taking a stand for, even if it makes you look silly. If I could have even the smallest effect, my own pride was a small price to pay.

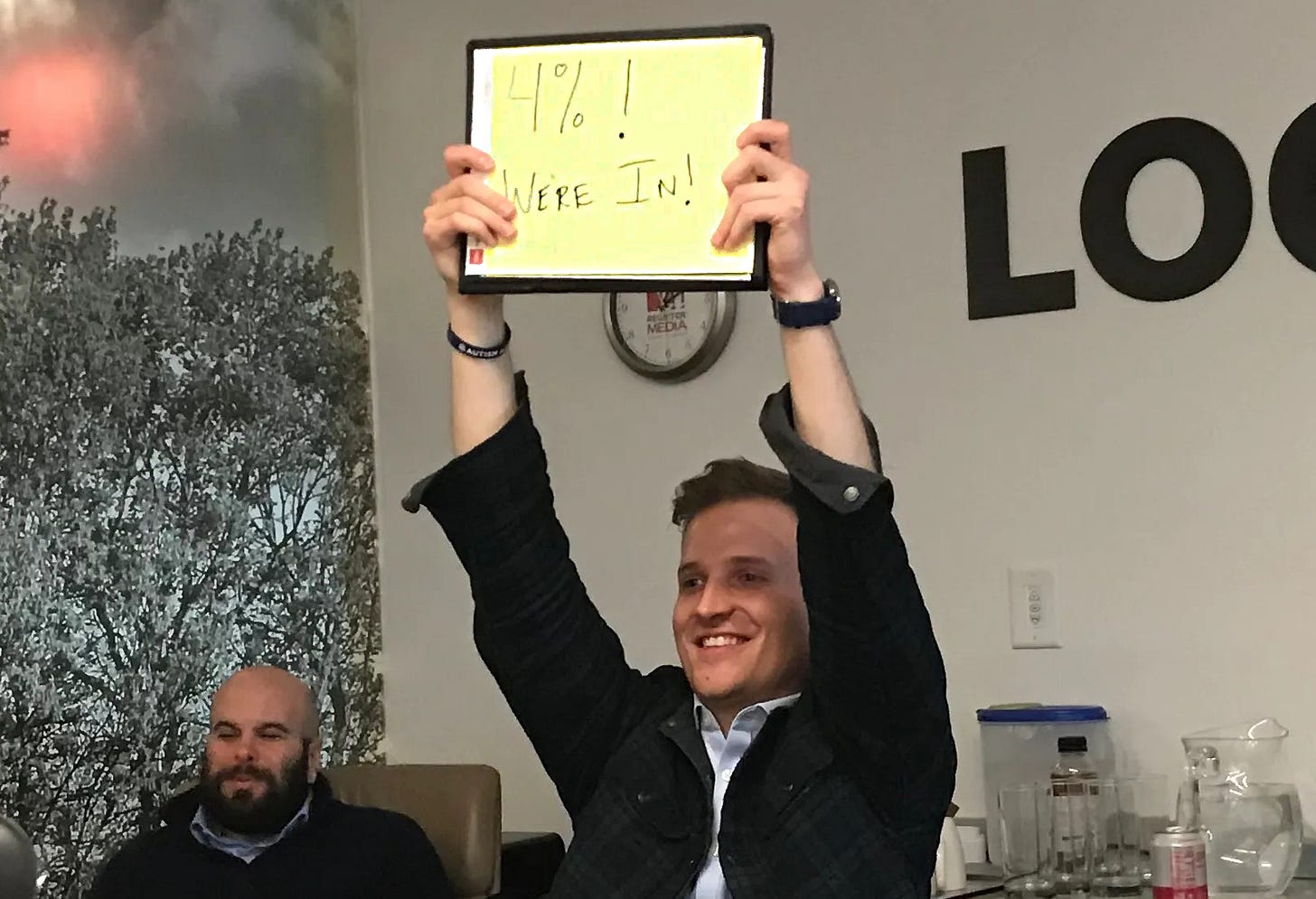

From December 2018 until Yang’s campaign ended after New Hampshire in February 2020, I was #YangGang. In a state whose votes didn’t matter, and with a full-time job and a mortgage to pay, I was never going to be a staffer. So I did what I could. I created separate social media accounts solely to boost Yang and UBI-related content, quickly gaining thousands of followers. I shared, liked, clicked, retweeted, and upvoted hundreds of thousands of posts, videos, and articles. Anytime someone mentioned Yang in a way that was either neutral or positive, they were rewarded with my clicks and likes. I strategically donated to the campaign every time they needed to qualify for a new debate, and within the 24-hour period just after one, when the press covers candidate fundraising as an indicator of performance.

I contacted everyone I personally knew who might be even remotely interested in the campaign. I got a Yang 2020 bumper sticker for my car (it’s still on there) and a Yang 2020 T-shirt that I wore whenever I went somewhere with large crowds. I had a “Humanity First” sign in the window of my house. I attended the Yang rally when he came to nearby Philly. I discussed Yang and UBI with thousands of people online, and even phone banked for the campaign at the end. I wrote essays, appeared on podcasts, tweeted more long threads than I can count, and made quotes into shareable memes. This wasn’t a sometimes thing, it was a daily routine. I did everything I could think of to move the needle, day in and day out, for more than a year.

Longshot is the parallel story to my own. It documents the many peaks and valleys of the campaign trail as only an insider’s perspective can. Graumann describes a memorable moment during the preparations for the second debate, after a disastrous first one, when Yang lashed out at the team:

“‘What’s the worst thing that happens to you guys if I bomb in Detroit? You get to put on your résumé, ‘Oh hey, yeah, ha ha, I worked for this shithead back in the day.’ Well guess what, guys? I’m the shithead!!’ His voice reverberated off the walls of our small greenroom. It was like we were all standing inside a bell that had just been rung. […]

‘From now on, I’m included in these conversations. I’m part of the strategy. You treat me like a human being, not some puppet you get to pull the strings of.’

We sat there looking at him in what felt like an eternity of silence. It could have been ten seconds or twenty minutes. I wasn’t counting. Our debate coaches were shook. They had never seen fired-up Andrew Yang. Finally, I looked over at Matt. And smiled.

‘It’s nice to have you back, Yang,’ I chirped.

‘Fuck!’ he exclaimed, not listening to me. Like he was still putting a cherry on top of the perfect tirade. But I meant it.

Andrew Yang was back.

Andrew yelling at us wasn’t just about him being frustrated. It was him getting his mojo back — and taking control back too. […] This was him telling us, Yeah. I fucked up the first debate. But I still willed this entire campaign into existence, and I won’t compromise who I am because of one off night.

And he was right. Damn, he was right. […] We needed to let Yang be Yang.

We were so caught up in the pressure of appearing on the national presidential debate stage that […] we’d forgotten the one thing driving every success we’d had: Andrew Yang.”

During the campaign, I came to learn that effective political activism is incompatible with rigid principles and total intellectual honesty. Something has to give. The ends, on some level, have to justify the means. This entails letting things slide you’d otherwise object to, making common cause with some people you don’t really like, signing onto some ideas you’re not crazy about as part of a broader package, and spinning bad news in a way that makes it seem like a blessing in disguise. It requires a level of Han Solo-like “Never tell me the odds!” self-delusion — of convincing yourself that you will win, no matter how slim your chances seem.

I had to pretend that Yang’s healthcare plan wasn’t the amateur-hour botch-job that it was. I had to spin Yang’s disappointingly plateauing poll numbers in the weeks leading up to the Iowa caucus as the result of outdated polling methods that were not accurately capturing the modern electorate. I had to pretend that Yang’s gaffes weren’t gaffes (like the whipped cream incident), that his faults were actually strengths, and that his math always added up, even when it didn’t. Because the moment I became objective, rigorous, and fully honest, I would no longer be an advocate. I’d be just another critic. Yang didn’t need another critic — he already had them in spades. Critics wouldn’t help improve his chances. This is the tension that lies at the heart, not only of political activism, but of all politics. Politics is the art of compromise — not only with others, but with yourself.

I bent my principles so that I could fight for Yang without having one hand tied behind my back, but I stopped well short of outright lies, fabrication, misinformation, and nastiness — something that cannot be said of our primary rivals. Longshot wisely skips over this saga, but Bernie Sanders supporters became infamous for swarming critics with abusive comments, lying about competitors, and trying to browbeat everyone who disagreed with them. Bernie’s online fans, many of whom had large followings, relentlessly smeared Elizabeth Warren, Joe Biden, and others. They spread falsehoods about Andrew Yang’s UBI gutting the social safety net and claimed that Yang was a billionaire (Bernie’s net worth was higher than Yang’s). They even accused Pete Buttigieg of conspiring with a voting technology company to steal the Iowa caucus. It reached the point that Sanders himself had to admonish his followers to cut it out on several occasions. Suffice it to say that emotions ran high, and that this particular segment of the American electorate did not endear themselves to me. Given the outcome of the race, I wasn’t alone. Leftists will always be their own worst enemies, and thank goodness for that — it saves the rest of us the effort.

But Yang lost, too. Badly. He left a slew of governors, senators, congressmen, and name-brand politicians in his vapor trail, but he ran out of steam when it counted. The irony is, as Graumann explores at length, that what made Yang remarkable and allowed him to break through the traditional gatekeepers to crack the big leagues is also what capped his ceiling once he arrived. “What got you here won’t get you there.” Politician-Yang would never have gotten off the ground, however once he had ascended to a certain level, he needed to “Reassure voters that [he was] safe, trustworthy, and broadly appealing enough to beat Donald Trump.” But when you spent two years building a brand to garner recognition, it’s not so easy to rebrand on the fly in a matter of weeks. As Graumann writes:

“We lost because he was a risky person to vote for, an outsider with big (and, to many, scary) ideas and no political experience, running in an election where the majority of Democrats were terrified and wanted the safest bet to defeat Donald Trump and restore order to a government and institutions that seemed to be crumbling.

It wasn’t because we didn’t knock on enough doors (we probably didn’t). It wasn’t because Andrew dropped too many f-bombs (he probably did). It wasn’t because the media was biased against him (they definitely were). And it wasn’t because his campaign team was too inexperienced (we definitely were). These hurdles didn’t help, but it was impossible to overcome the macro factors. We say the game has changed, and it clearly has, but not enough for Andrew Yang to beat Joe Biden. We’re not there yet.”

He later continues:

“Realistically, we were never going to win this election. […] I didn’t know that when we started, or even in the fall of 2019. I believed with every fiber of my being that we had a shot.

But looking back, it was never — believe me, never — going to happen. We were a longer than longshot, and while we shocked the world and smashed through even the most generous expectations, we still had a massive deck stacked against us.”

During the many highlights of the campaign — the viral moments, the excellent speeches or debate performances, the impressive fundraising milestones, the celebrity endorsements (such as Elon Musk, Donald Glover, and Dave Chappelle) — it really did seem as though this was the beginning of an insane snowball effect. This is the kind of wishful thinking and utter lack of objectivity that activism inspires in you. There’s a reason why every single hardcore activist, however fringe their cause, is utterly convinced that they speak for the people, that their ideas are, in fact, widely popular, even when the polls suggest otherwise. In the case of Andrew Yang and universal basic income, at least in 2020, it wasn’t meant to be. But as the polls have shown, Andrew Yang’s campaign did in fact change the conversation, and the before-and-after data on public support for universal basic income is staggering. He did that, with Graumann’s help. And in some minuscule way, with mine, too.

I left it all on the field, and in the end, even though I had dared to hope, I was at peace with defeat. I had done my part. As awkward, uncomfortable, time-consuming, and sometimes embarrassing as it all was, the thought of having been too lazy to help, too self-conscious to be vulnerable, and too timid to dream big was far worse. There is something ignominious about admitting to being so swept away in a cause like this, especially if one seeks to be seen as a serious person, but I wouldn’t trade my experience and what it taught me, both about politics and myself, for anything. It was a wild ride, and Longshot is as captivating an account of it as you’re ever going to see in print.

See also: “The Lessons of New York City’s Mayoral Battle”

Subscribe now and never miss a new post. You can also support the work on Patreon. Please consider sharing this on your social networks. You can reach me at @AmericnDreaming on Twitter, or at AmericanDreaming08@Gmail.com.

Thanks for sharing that, brought back a lot of memories and tears for me. We all need to keep dreaming big.

This is easily the best postmortem of Yang's presidential campaign that I've read.