A few items before the article. Contributor Alexander von Sternberg has a new piece out in Queer Majority about the crisis of masculinity: “Men Aren’t as Doomed as We Think.” Alex and I also appeared on the Bridgebuilding podcast to discuss journalism, new atheism, the intellectual dark web, political realignment, and more.

Two years ago, I wrote “We All Live in the Truman Show Now”, an essay arguing why the right to privacy matters and lamenting the shifting norms and attitudes surrounding privacy, especially among the younger generations. To illustrate my point, I posed the following thought experiment:

“Sexual assaults often have no witnesses, and can leave no evidence behind, becoming a matter of he-said-she-said in which a guilty perpetrator can escape justice. Why not install surveillance cameras in every room in every building in the country that can alert the authorities if any criminal behavior goes down? It’s undeniable that this would massively crack down on sexual assault, and probably many other crimes, too. What’s that, you don’t want the cameras in your home? ‘Why are you in favor of rape?’ ‘Perhaps you’re a rapist yourself?’”

I took anti-privacy policies to their reductio ad absurdum in order to identify a line that no one, I thought, would ever want to cross, to show that the logic behind privacy in this extreme case isn’t fundamentally different from others. I never dreamed that my preposterous-on-purpose hypothetical would be the sort of thing any appreciable amount of people would ever actually support. It appears that I was wrong.

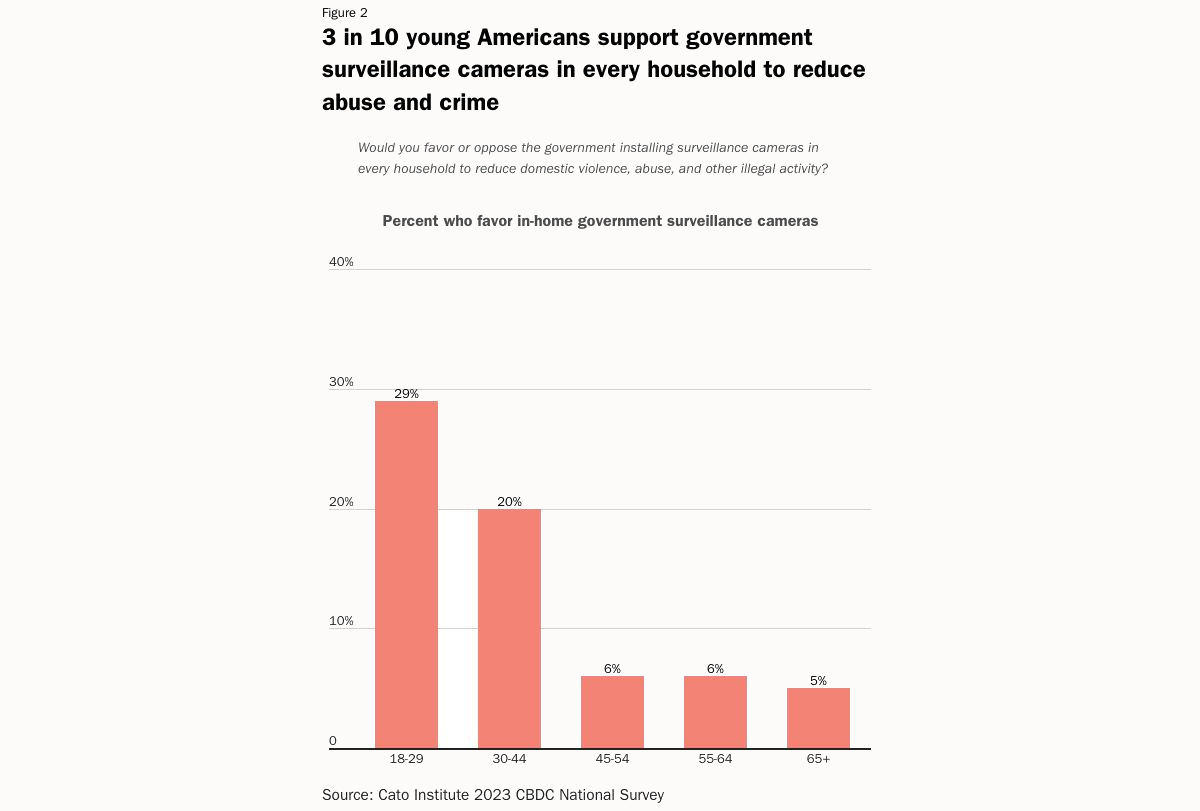

A new survey from the Cato Institute found that 29 percent of Americans aged 18 to 29 (roughly Gen Z) favored “the government installing surveillance cameras in every household to reduce domestic violence, abuse, and other illegal activity.” Millennials, (aged 30 to 44) were not far behind with 20 percent support. This compares to about six percent support from all age cohorts above 45. To translate this into raw numbers, that’s nearly 35 million US Zoomers and Millennials who think it’s a good idea to live under direct, round-the-clock government surveillance.1 These are stunning numbers, even if they’ve been a long time coming. Privacy, as I wrote in 2021, is inextricably linked to freedom. We cannot be free if we do not feel free to be ourselves, and we cannot be ourselves under a state of surveillance. It should not surprise us then that young people care less, not only about privacy, but about freedom more broadly.

These Cato results line up closely with a 2019 Pew report that found 32 percent of US adults aged 18 to 29 believed the data collected about them was beneficial. Likewise, 41 percent of young people did not support the right to have one’s health data permanently deleted. This is part and parcel of a pervasive trend of successive generations favoring safety over freedom. We see this most clearly in attitudes about free speech.

When generically asked if they support free speech, nearly everyone unsurprisingly says yes. When asked more probing questions that test the mettle of their professed principles, a different picture emerges, especially for young adults. Only 40 percent of high school students in 2022 agreed that people should be allowed under the First Amendment to say whatever they want, even if it is offensive. 44 percent disagreed that musicians should be allowed to sing offensive lyrics. 43 percent said that news organizations should be subject to government censorship. And 62 percent of teens aged 13 to 17 said feeling safe and welcomed online matters more than being able to speak one’s mind freely.

College education does not seem to improve matters. 41 percent of college students in 2022 could not agree that university students should be exposed to all types of speech, even if they find it offensive or biased. Only 39 percent opposed college speech codes restricting speech “that would be permitted in other public places.” Among 18- to 29-year-olds, only 42 percent said the government should not regulate professors’ speech, and 36 percent believe that bigoted, untrue, or “anti-democratic” speech should sometimes be shut down. The irony of squelching free speech in the name of democracy would be delicious if it weren’t mingled with the taste of bile rising my throat.

The thought patterns and general ethos one observes from today’s youth, both online, in everyday life, and in the data, can at first glance be taken for straightforward authoritarianism. But while these attitudes are, in fact, authoritarian, it’s not the kind of authoritarianism we usually think of. The desire to dominate or exert one’s will over others, while maintaining freedom and autonomy for oneself, is a regrettable but all-too-human impulse. What makes a disquietingly large portion of Gen Z so deranged is not that they are would-be tyrants seeking to lord over others, but that they are anxious, stunted, perma-children; Peter-Pansies who themselves desire to live under the watchful eye, not of Big Brother, but of Big Mommy and Daddy. They do not hate the freedom of others as much as they are terrified at the thought of freedom and the adult responsibilities it entails. The first generation raised by the internet, smartphones, social media, and helicopter parents; the first generation without free play, who never got laid in high school and were never out of earshot of authority figures, have taken their infantilized mindset out into the world with them. I say “out into the world” figuratively, of course.

This didn’t start with Gen Z. It began with Millennials — my generation. Everything wrong with Gen Z is simply a concentrated and intensified version of the trends and forces that shaped us. In 2015, 40 percent of Millennials supported the government censoring speech deemed offensive to minorities. In 2005, only half of higher schoolers polled said that “newspapers should be allowed to publish freely without government approval of stories.” This prompted Bill Maher, in his book, New Rules: Polite Musings from a Timid Observer (2005), to write:

“The younger generation is supposed to rage against the machine, not for it; they’re supposed to question authority, not question those who question authority — and what’s so frightening here is that we’re seeing the beginnings of the first post 9/11 generation, kids who first became aware of the news under an ‘Americans need to watch what they say’ administration, kids who’ve been told that dissent is un-American.”

We have seen where these beginnings have led. A multi-factorial confluence of pressures — economic, cultural, parental, technological, political, governmental, and psychological — are chipping away at our resilience. And it turns out that the unresilient are not well-suited to the job of maintaining liberalism. The unresilient want parental substitutes to solve all of their problems for them. This is just as true of those on the political right who think the woes of modernity are best remedied by clinging to the pant leg of a daddy figure to carry them back in time to some imagined yesteryear.

What worries me is what happens in 30 years, when Gen Z begins taking the reins of power? What happens with the generation that comes after them? People do mature over time. The question is, when they enter adulthood beginning at successively lower baselines of maturity, will it be enough by the time the future is in their hands? Or will we, by that point, have Big Mommies to do our worrying for us?

See also: “What Does It Mean to Grow Up?”

Subscribe now and never miss a new post. You can also support the work on Patreon. Please consider sharing this article on your social networks, and hit the like button so more people can discover it. You can reach me at @AmericnDreaming on Twitter, or at AmericanDreaming08@Gmail.com.

Considering that Gen Z grew up with devices in their pockets that allow anyone to be watched at any time, this is not a surprise.