Jamie Paul here. This post is by Contributor Alexander von Sternberg, but I also have a piece out in Queer Majority reporting on a new law in Florida: “Florida’s War on Pride.”

North Korean defector Yeonmi Park has reentered the internet zeitgeist nearly a decade after her rise to minor celebrity, thanks, as always, to memes. In May 2023, a video clip of Park speaking about children in North Korea being made to “eat mud” went viral on Twitter and spread across social media. Another clip from her 2021 appearance on The Joe Rogan Experience soon made the rounds in which she asserted that North Koreans had to periodically channel their inner Superman by physically pushing trains, because “there was no electricity” (a single railcar weighs between 30–80 tons). These helped revive more bizarre and ideologically-motivated claims Yeonmi had previously made, such as her contention that the “woke” milieu of Columbia University was comparable to North Korea. Amid the fever pitch of online noise — especially on Twitter and Reddit, where Park’s honesty has been a point of contention for two years — the Yeonmi Park Know Your Meme page has likely seen more traffic than ever.

Interestingly, this recent meme-ing and criticism of Yeonmi Park isn’t coming from tankies and defenders of the so-called Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK); but rather from conservatives, libertarians, and classical liberals. As baffling as this might initially seem, it makes sense that thoughtful folks in those camps are well past tired of what seems to be a pattern for Yeonmi. This makes for a precarious situation. While some of us feel compelled to criticize Park’s antics despite our loathing of the Kim regime, there are also DPRK apologists and communist LARPers who routinely attack Yeonmi and her fellow defectors in their quest to minimize North Korea’s brutality. This is why the latter group necessitates the former. Anyone to the right of Marx has an obligation not to indulge in flights of dissident fancy just because they think it gives communism a black eye. The fact is, Yeonmi Park’s long and troubled relationship with the truth does more harm than good to the cause of exposing the atrocities of North Korea. The apologists for autocratic systems couldn’t ask for better propaganda, as we have seen with the Guatemalan Civil War and WWII Japan.

The questions surrounding Yeonmi Park’s credibility stretch back to a 2014 article in The Diplomat by Mary Ann Jolley titled, “The Strange Tale of Yeonmi Park.” The piece was written a few months after Yeonmi’s Western debut, in which the 21-year-old tearfully recounted fleeing the Kim dynasty’s cesspool with her family at the age of 13, crossing the Gobi desert on foot, and witnessing all manner of horrifying depredations. As Jolley summarizes:

“Wearing a pink, traditional Korean dress with its high waist and voluminous skirt, Park stood before the lectern at the One Young World Summit in Dublin and in between long pauses, wiping tears from her eyes and holding her hand to her mouth as she composed herself, she told of being brainwashed; of seeing executions; of starving; of the slither of light in her darkness when she watched the Hollywood blockbuster Titanic, and had her mind opened to the outside world where love was possible; of having to watch her mother being raped; of burying her father on her own at just 14; and of threatening to kill herself rather than allow Mongolian soldiers to send her back to North Korea. She talked about following the stars to freedom and then ended with her signature sign off, ‘When I was crossing the Gobi desert, scared of dying, I thought nobody cares, but you have listened to my story. You have cared.’”

It’s no surprise that the speech became a smashing, viral success; it contained every hallmark of a heart-rending and ultimately triumphant story that spat in the face a totalitarian hellscape while lionizing the West and its values. As Jolley noted, “You’d have to have been inhuman not to be moved.”

However, questions began trickling in. While there were broader skeptics, like Swiss businessman Felix Abt, who lived in North Korea for seven years and dismissively claimed that things weren’t that bad, those who followed The Diplomat’s investigatory lead have pointed out more specific problems with Yeonmi’s story. By 2014, she had been starring in a reality TV show in South Korea in which she was branded as “the Paris Hilton of North Korea.” During an episode aired in 2013, Yeonmi proclaimed that it was actually her mother who should be called the “Paris Hilton of North Korea.” She also said that her mother carried a Chanel bag while they lived in North Korea, and when asked by the host if they were rich, Yeonmi indicated that yes, they were. Her mother also added on that same show that “We were just never in a position where we were starving”, contrasting with Yeonmi’s later claims on the BBC that she at times had to subsist on grass and dragonflies. A far cry from the tales of abject immiseration she would increasingly tell after moving to the United States.

The inconsistencies with her narrative didn’t stop there. For example, her claim that at the age of nine, she saw her best friend’s mother publicly executed at a stadium in Hyesan. The crime? Watching a South Korean drama on DVD… or was it a James Bond film? Or a Hollywood movie? (The story changed multiple times). According to Andrei Lankov, an expert on North Korea and professor at Kookmin University in Seoul who lived in North Korea as a Soviet exchange student in the 1980s, the idea that anyone would be executed for consuming Western or South Korean media is doubtful. “An arrest for such action is possible indeed,” he said, “but still not very likely.” In addition, many North Korean defectors from Hyesan have questioned Park’s account on the grounds that mass executions never took place in stadiums; rather, they occurred outside the city or at the airport, and, as best as can be ascertained, rarely for anything less than murder and theft of state-owned property.

Other discrepancies have arisen regarding her escape story. Yeonmi originally claimed (repeatedly, and often) that her entire family escaped North Korea together. After some time had passed and it became clear that her account didn’t have quite enough dramatic oomph, however, Yeonmi began saying that her father hadn’t been with them. In this second version of the story, her mother offered herself up to a human trafficker for rape in order to spare Yeonmi and pay for her father to be smuggled across the border. While it’s certainly possible these stories have a common middle ground, it’s hard to reconcile the 2014 telling of the story with this more agonizing 2015 version that coincidentally surfaced just as she was promoting her first book, In Order to Live (2015).

These irregularities have been chalked up to many factors. Yeonmi herself attributed the inconsistencies to a “language barrier” in her response to The Diplomat’s article (featured at the bottom of the page) and imperfect childhood memories. Commentators have also discussed the fact that life in North Korea necessitates lying in order to survive, as well as the tendency for victims of trauma to have faulty recollections. These points are, for the most part, certainly well-taken, but the contradictions have continued alongside Yeonmi’s rise to further prominence, not to mention that her English fluency could only have improved during the last decade. The increased scrutiny she has faced stems from her 2021 appearances on popular “Intellectual Dark Web” podcasts, like those of Joe Rogan, Jordan Peterson, Lex Fridman, and Michael Malice, all of whom greeted her testimony with credulity. And with the release of Park’s second book, While Time Remains: A North Korean Defector's Search for Freedom in America, in February 2023, critical eyes were once again trained on her.1

The renewed spike in Yeonmi Park skepticism isn’t merely the product of a flood of online and alternative media attention. The resurgence owes just as much to the way in which she has reinserted herself into the limelight via the American culture wars. As previously mentioned, Yeonmi reappeared with a rhetorical vengeance in the pages of the New York Post, decrying wokeness on college campuses and making superficially compelling but hyperbolic comparisons to the DPRK’s culture of silencing dissent. To no one’s surprise, the anti-woke brigade immediately latched onto Park like barnacles on a passing whale.2 As the writer John Lee wrote for NK News in June of 2021:

“Park knows full well what kinds of soundbites right-wing Fox [News] wants to hear. It was probably a big win for the network to get a North Korean celebrity defector to claim that American progressives and social justice warriors — Fox News’ sworn enemies — are even more unhinged than the North Korean regime, which itself is all too often depicted as irrational and ridiculous by many news media outlets.”

To many watching — especially those who genuinely care about the plight of North Koreans — it seems clear that Park has been willing to say or do whatever it takes to stay relevant, sell books, and secure speaking fees. She injected herself into a conflict not defined by a concern for human rights in a place where they don’t exist, but rather by low-resolution caricatures of the American right’s ideological enemies. If you can compare American progressives to the North Korean regime, you don’t have to engage with their ideas, just as if progressives can compare conservatives to Nazis, they don’t have to engage with them either. As is often the case, the culture wars are a vehicle for successful ventures.

None of this is to say that Park has done no good at all, nor that the DPRK is anything short of a moral abomination. I sympathize with the organizations who have been financially backing Yeonmi and share some of their goals. I agree with the assessment made by Christopher Hitchens that the North Korean regime is led by “racist dwarves” who gag in disgust at the idea of their South Korean brethren marrying black American soldiers. The DPRK — whose official name is molasses-thick with irony — is, as Hitchens put it, defined by “giant mausoleums and parades that seemed to fuse classical Stalinism with a contorted form of the deferential, patriarchal Confucian ethos.” Hitchens aptly described the state as a “totalitarian ‘military first’ mobilization, [that] is maintained by slave labor, and [that] instills an ideology of the most unapologetic racism and xenophobia.” North Korea unquestionably occupies the lowest rung of human freedom and dignity. This is why it’s so important to criticize figures like Yeonmi Park, because all they ultimately do is make things worse.

In 1992, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to an unassuming indigenous K’iche’ Guatemalan woman named Rigoberta Menchu. The Nobel was given in recognition of her work in advancing social justice, her harrowing 1983 memoir, I, Rigoberta Menchu, as well as all she had endured and fought against during the Guatemalan Civil War of 1960–1996. She recounts untold suffering at the hands of the Guatemalan military cracking down on the leftist rebels, including members of her own family. As a 1998 Washington Post article recounted:

“During the height of Guatemala's civil war […] dozens of her neighbors and friends were murdered and kidnapped in a war between leftist guerrillas and government troops that claimed an estimated 100,000 lives and left an additional 40,000 people unaccounted for.”

Her efforts — which, as the Post put it, “helped turn an international spotlight on the atrocities committed against indigenous populations in Guatemala and throughout Latin America” — turned her into a celebrated feminist icon in leftist circles the world over. Her memoir made its way into myriad history and global studies classrooms (including one of my own), and was counted among the foremost pieces of effective whistleblowing literature in the modern era. The Nobel Prize was, it appeared, well-deserved. But appearances can be deceiving.

An in-depth investigation conducted by anthropologist David Stoll, published in his 1998 book, Rigoberta Menchu and the Story of All Poor Guatemalans, revealed that many parts of Menchu’s story were fabricated out of whole cloth. Stoll’s exposé opened the door to further scrutiny from other sources. As it turned out, there were many discrepancies in her story.

Menchu claimed that she was an uneducated indigenous woman who spoke no Spanish, but a Guatemala City nun at what the Washington Post called “a prestigious convent school” described Menchu as “a star pupil.” Menchu claimed that her younger brother died of starvation, but a report by the New York Times found that this brother never existed. Her other brother, she claimed, was burned alive by Guatemalan troops as she and her parents were forced to watch. The Times reported that while he was tragically murdered, it was under entirely different circumstances, and she and her parents were not present. And Menchu’s assertion that a family land dispute, as the Washington Post described it, “represented numerous Latin American battles between rich European descendants and poor peasants”? According to Stoll, it was “actually a feud between warring members of Menchu’s own Mayan clan.”

The fallout from these revelations was, sadly, predictable. The broader Western left rushed to protect their star witness to the evils of Western interventionism (thanks to the US‘s role in the abuses during the war). They were more than happy to humor her insistence that “my truth” allowed for all of her tales to be true in spirit — that this was just an expression of the “testimonio genre” in which Menchu’s story was really that of all of indigenous Guatemalans. It’s curious that this was not how the book was described until after the controversies regarding its veracity were made public. That Rigoberta Menchu was exposed as a fabulist playing on progressive sensitivities mattered less than the need to preserve the narrative she had crafted so that the cause it bolstered could be preserved.

To this day, Menchu’s reputation has remained largely unbesmirched by these claims, due in part to the Nobel Group simply dismissing the revelations as irrelevant to “her efforts.” She has also been given cover by leftists in both academia and journalism who essentially admit that while her testimony is fanciful, the “Truth” behind it is accurate, so the deception was justified. To be clear, the point is not that nothing happened to the indigenous peoples of Guatemala during the Guatemalan Civil War. The facts speak for themselves. But let’s be honest: did the world need Rigoberta Menchu for these terrible crimes to be uncovered? Some may say yes, but this is a “Great Man of History” fallacy. Menchu played a role, and a role only. And considering how nakedly self-serving her falsehoods were, and how totally they were laid bare, all she managed to accomplish was to needlessly muddy the waters of what really happened in the Guatemalan Civil War.

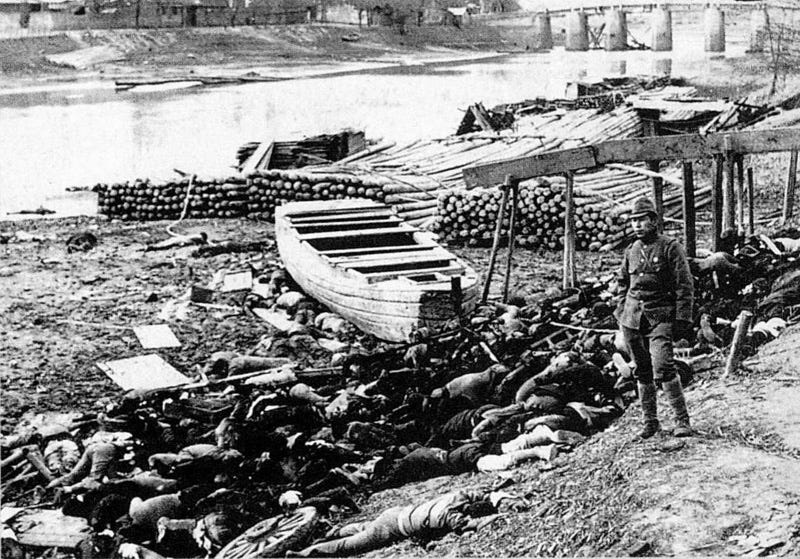

The real consequences of taking figures like Yeonmi Park (or Rigoberta Menchu) seriously despite their tenuous relationship with the truth — not their truth — carries a darker edge. I encountered this firsthand while researching the Japanese invasion of China in 1937 and the story of a particular Nazi — that is, the “Living Buddha of Nanking” John Rabe — who actually saved a quarter million Chinese civilians from imperial Japanese barbarism. The most well-known secondary source covering this subject is the late Iris Chang’s incredible and horrifying book, The Rape of Nanking (1997).

The book faced controversy after its publication, from both Western and Japanese scholars who pointed out a number of minor but nonetheless factual and interpretive errors she had made. Chang’s own mental illness — perhaps exacerbated by her research, according to her mother — played a part in the controversy, both in explaining her mistakes and in explaining why her work was so easy for revisionists to dismiss. This became even more apparent and tragic after she shot herself in 2004 during a nervous breakdown, but the reality was she had, at times, played a little fast and loose with the facts.

While there are obvious differences between Iris Chang’s work and that of Yeonmi Park, the reactions to both from apologists of the regimes they criticized have been identical. After the publication of The Rape of Nanking, controversy surrounding the book erupted in Japan, primarily from their own political right and ultranationalist circles who have long minimized and even fraudulently denied the realities of the Nanking Massacre. This impulse even animated the recently-assassinated former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who likely co-authored a paper denying the massacre. And when it became clear that the book contained some errors, the Japanese right went for the jugular. As liberal Japanese historian Akira Fujiwara noted in a Los Angeles Times interview:

“A campaign to deny the Nanking massacre itself by presenting the weaknesses of Iris Chang’s book is being developed. The massacre denial groups have been using these kinds of tactics to maintain there was no massacre by presenting the contradictions in testimony quoted or by the use of inappropriate photos.”

Iris Chang serves as a warning of the effects of sloppy scholarship, but hers is a fundamentally different case from that of Rigoberta Menchu and Yeonmi Park, whose stories are strikingly similar in many respects. Both are first-person embellishments nevertheless ensconced within real events; which is what makes these figures so unseemly. Park and Menchu have weaponized the horrors that they know have occurred in order to turn a handsome profit. There are plenty of accounts that support both of their broader claims, and far better and more reliable collections and testimonials, such as Victoria Sanford’s Buried Secrets: Truth and Human Rights in Guatemala (2000), or Chol-hwan Kang’ and Pierre Rigoulot’s The Aquariums of Pyongyang: Ten Years in the North Korean Gulag (2000).

The problem is that neither of these works (or others like them) cut corners in order to appeal to particular Western political biases. The more well-sourced and high-quality accounts of evil regimes don’t sufficiently spoon-feed their intended audience confirmatory narratives that their enemies are bad and that the readers themselves are good. Rigoberta Menchu and Yeonmi Park are perfect analogues for one another: Menchu, a victim of savage Western-backed right-wing authoritarianism and genocide, is a perfect victim for the Western left; and Park, a victim of a savage, Marxist-Leninist totalitarian state that has enslaved its people, is a perfect victim for the Western right.

It’s not difficult to imagine what the response to Yeonmi Park’s spotty record has been, both from Western communists and self-described “anti-imperialists”, and, more crucially, from North Korean state media itself. John Lee wrote that “there is no doubt” that Yeonmi Park wants all North Koreans to be as free as she is. That may very well be, but it’s fair to question how serious she is about liberating the people of North Korea when her mendacity has only tarnished her credibility — and that of her fellow defectors — thus strengthening the cases made against them by the Kim regime. Being truly committed to ending any kind of tyranny — whether of a nation, or a company, or even just an abusive partner — means never giving the tyrant anything they can use against you. And for the DPRK and its apologists, Yeonmi Park is the gift that keeps on giving.

See also: “The True Darkness of Cancel Culture”

Subscribe now and never miss a new post. You can also support the work on Patreon. Please consider sharing this article on your social networks, and hit the like button so more people can discover it. You can reach me at @AmericnDreaming on Twitter, or at AmericanDreaming08@Gmail.com.

Building off of the reporting in The Diplomat, multiple Reddit threads calling her claims into question have formed, and from there, some impressive YouTube documentaries and commentaries, all appearing during the last two years.

While also ironically utilizing the same rhetorical tool weaponized by the #MeToo movement — faulty memory due to trauma — that they were all too willing to dismiss.

Excellent article from beginning to end