I’m taking next week off. Articles will resume as normal the following week. Happy New Year!

For more than a decade now, I’ve been setting myself yearly reading challenges on GoodReads. 2023 turned out to be an incredibly busy year. One thing they never tell you about becoming a full-time writer is that when you clock out after a day of reading, rereading, writing, editing, and researching, the last thing you’re in the mood to do is read. I managed to read 30 books, my lowest number since 2016. This post will include brief reviews of 19 of them. You can see the full list here. Keep scrolling and you’ll also see American Dreaming’s top 10 essays of the year.

My Favorite Books Read in 2023

“End Times: Elites, Counter-Elites, and the Path of Political Disintegration” (2023) by Peter Turchin

Of the dozens of books I read every year, there’s usually one or two that blow me away with how much sense they make — books that offer such illuminating insights and perspectives that they change the way I think about certain issues. End Times is one such. I’m a latecomer to his work, but Peter Turchin’s twin lens of “popular immiseration” and “elite overproduction”, as historically reliable precursors of political crises, slots so many things into focus it’s kind of eerie. No one lens is singularly definitive, of course, but I can’t imagine any coherent macro-view of today’s sociopolitical landscape that doesn’t at least include analysis along the lines of End Times.

Turchin himself also shared my original GoodReads review on Twitter, which was pretty neat.

“Pet Sematary” (1983) by Stephen King

This was one of the most disturbing and emotionally harrowing novels I’ve ever read. A masterpiece of horror that charts the depth of love and grief, Pet Sematary chills to the bone not through ghouls that jump from the shadows, but from the inexorable march of the damned that, however doomed, is one we can all too easily picture ourselves walking. There’s a reason why this book disturbed King so much it was almost discarded. The road to hell may be paved with good intentions, but the road to the Pet Sematary is paved with love. Few things could be more haunting.

(Please do yourself a favor and skip the film adaptations, they’re awful.)

“Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years and the War Years” (1926, 1939, 1954) by Carl Sandburg

Carl Sandburg’s Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Lincoln charts the 16th president’s life in almost painstaking detail, from thoughtful child, to melancholy young man, to country lawyer, to politician, president, and eventually legend. As much a work of history as biography, with many chapters in which Lincoln takes a backseat to the events and figures of the era, Sandburg’s tome offers not merely a whole-life accounting of Lincoln, but a solid history of the US Civil War as well.

The style of writing is noticeably artful and even at times poetical, in contrast with the comparatively more straightforward prose often found in more contemporary presidential biographies. At points, this makes for emotionally stirring writing, especially in the final chapters, but more than a few times I found myself having to reread a sentence because the style was getting in the way of the communication. Quibbles aside, an excellent work.

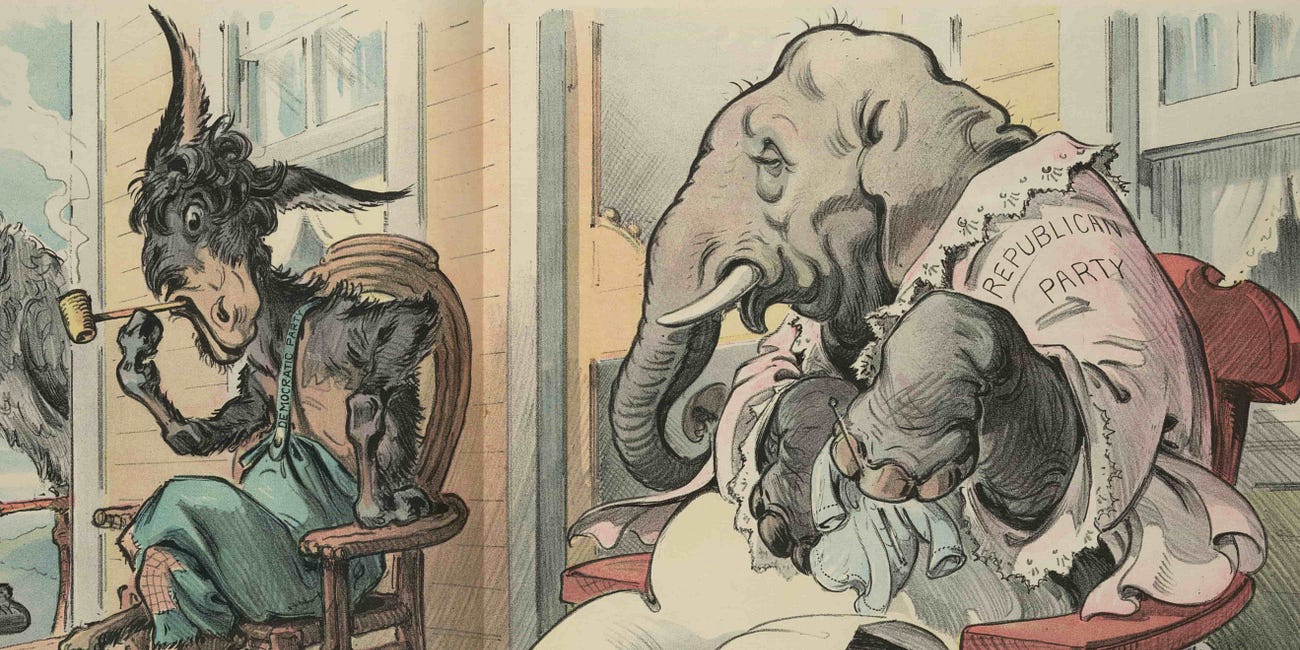

“Notes on Democracy” (1927) by HL Mencken

It’s become so axiomatic to reflectively and unconditionally extol the inherent goodness of democracy that it seems jarring and yet refreshing to read a critique of it. In this instance, not the critique of one who seeks to replace democracy with some alternative system, but of one who simply revels in the act of colorfully lambasting its absurdities. Mencken gets so much right — and most of what he gets wrong wasn’t wrong when he wrote it. As a work of historical political analysis and social commentary, it’s brilliant. As a work of contrarian humor, it’s simply delicious.

Other Nonfiction Selections

“Anne Frank’s Diary: The Graphic Adaptation” (1947, 2017) by Ari Folman (adapter), David Polonsky (Illustrator), and Anne Frank (Original text)

I read this graphic novel version of Anne Frank’s Diary for a Queer Majority piece I wrote covering the controversy surrounding its removal from school libraries in Florida. Evidently, some right-wing culture warriors were offended that it had two pages about a crush Anne had on another girl. The article, Banning Anne Frank’s Diary, in the Name of Freedom, ended up being QM’s sixth most-read piece of 2023. As for the book itself, I can’t recommend it enough. As I wrote in the piece:

“This abridged retelling of Anne Frank’s diary — adapted by Oscar-nominated Israeli film director Ari Folman and wonderfully illustrated by Israeli artist David Polonsky — is not a mere dumbing-down and reformatting of the material for a younger audience. Rather, it captures the humanity, quirkiness, and emotional complexity of this young girl far better in some ways than prose alone ever could. As Folman writes in commentary at the end of the book, ‘We made no attempt to guess in what manner Anne might have drawn her diary if she had been an artist instead of a writer. We did, however, try to visually interpret and preserve her powerful sense of humor, her sarcasm [...], and her obsessive preoccupation with food.’ [the graphic adaptation repeatedly dwells on coping with the endless hunger in hiding.]

“They achieved all that and more. The reader is transported into Frank’s vivid imagination, insecurities, anxieties, frustrations, romantic yearnings, and most of all — her fathomless Jewish capacity for finding humor even in the darkest situations. Certain portions of the original text, especially toward the end of the diary when Frank was blossoming into a talented writer, were reproduced in full.”

“It’s Not About Whiteness, It’s About Wealth: How the Economics of Race Really Work” (2023) by Remi Adekoya

In his refreshingly global examination of race, Remi Adekoya zooms out from the Anglophone world to explore the wider issues that underlie the attitudes, perceptions, biases, and disparities between commonly identified racial groups. If you’re coming into this expecting it to be another regurgitation of anti-racist platitudes or anti-woke polemics, you will be disappointed. While It’s Not About Whiteness is light on solutions, it does such an insightful and data-driven job at diagnosing many of the root problems within race relations that I’d recommend it to anyone.

“The Fortunes of Africa: A 5,000-Year History of Wealth, Greed, and Endeavor” (2014) by Martin Meredith

Telling the entire recorded history of the world’s second largest continent in a single book is simply an impossible task. Martin Meredith did as fine a job as anyone could hope for, but the reader is left utterly overwhelmed by the mind-breakingly sprawling and multifaceted history of hundreds of peoples and countries and clashes and intersections all coming and going and coming again. The book is at once fascinating and also numbing. I don’t fault the author for this. At the sentence level, Fortunes is well-written and accessible, and the chapters are organized both by region/country and chronology. The best remedy here is for readers not to treat this book as a one-stop primer on African history, but to familiarize themselves with the subject matter beforehand. African history is such a big subject — and one that so few Westerners are ever taught — that one needs a primer for the primer.

“On Writing and Failure: Or, On the Peculiar Perseverance Required to Endure the Life of a Writer” (2023) by Stephen Marche

On Writing and Failure is better understood as a “philosophy of writing” rather than career advice or writing tips. This short book packs an incredible number of wild stories from literary history and the contemporary writing industry that lend something more useful than any conventional advice: perspective. A thoroughly enjoyable, quick, and, in my case, admittedly self-indulgent read.

“The American Language” (1919) by HL Mencken

A surprisingly thorough exploration of American English, The American Language is interesting both because of how relevant it remains a century after publication, and also because it illustrates how much language has changed in the time since. I went into this book expecting Mencken to provide a light and entertaining treatment of an ordinarily dry subject matter. He didn’t disappoint with his writing style — Mencken never does — but the treatment turned out to be more in-depth than I anticipated, which was a pleasant surprise.

“How Elites Ate the Social Justice Movement” (2023) by Fredrik deBoer

A far more niche book than readers might suppose going in, How Elites Ate the Social Justice Movement is, at bottom, a polemic aimed at a very narrow audience. Besides providing some standard fare recap and analysis of 21st century social justice politics, deBoer takes great pains to emphasize his leftist bonafides and find common ground with contemporary progressives. He does this in order to make the case that intersectional identitarianism is an ineffective way of advancing a left-wing political agenda. He makes that case very well, but readers who are not themselves leftists, who may be coming to this book as fans of deBoer’s culture-writing, will often feel like an acquaintance invited to a family dinner that devolves into heated arguments. That’s how I felt, at least.

Other Fiction Selections

“There There” (2018) by Tommy Orange

Orange skillfully captures the sense of a Native American culture disconnected, conflicted, fading, and adrift, and the self-destructive feedback loops born of it. And the guy knows how to write. He’s got that style of the moment. Minimalist but deep, raw yet refined. He writes chapter after chapter that should feel like self-indulgent identitarian navel-gazing, but he does so with such unpretentious honesty that it works. While reading There There, I was often reminded of Jay Caspian Kang’s The Loneliest Americans (2021), despite the latter being about Asians and not a novel. But where Kang’s memoir veered into what I consider plain neuroticism, Orange, with the versatility of fiction and a far deeper well of ethnic loss to draw from, crafted an artful yet down-to-earth lament.

Shoutout to one of my contributors, Timothy Wood, for recommending this book.

“The Last Election” (2023) by Andrew Yang and Stephen Marche

The Last Election is a spellbinding political thriller that, although a work of fiction, believably pulls back the curtain on the inner workings of politics, government, and journalism to paint an all-too-plausible scenario of how a hypothetical breakdown of American democracy might unfold. As pure entertainment, The Last Election is impossible to put down and, in fact, can be read in a sitting or two. As a warning about the direction in which the US is headed, it leaves the reader with much to disquietingly chew on.

“Skeleton Crew” (1985) by Stephen King

A fantastic collection of horror-themed short stories and novellas. What is there to say? The guy’s a master of the genre. Skeleton Crew is one gem after the next.

“The Lost Metal” (The Mistborn Saga, book seven) (2022) by Brandon Sanderson

(Spoiler free) The original Mistborn trilogy (2006–2008) is a hard act to follow. The succeeding three books were thoroughly fun, but although they took place in the same Cosmere as their predecessors, they were not in the same universe as works of fantasy. As Sanderson’s sprawling, interconnected web of worlds and novels continued to grow with other series like The Stormlight Archive, Mistborn, it seemed, had diminished into a glorified “buddy cop” detective serial, full of jokey banter and Allomantic gunslinging, but light on nearly every epic fantasy hallmark readers had come to expect. The Lost Metal redeems Mistborn era two.

Like a snap-zoom out, Sanderson dramatically widens the scope and joins the broader Cosmere. The stakes are higher, the scale is larger, the mysteries more intriguing, and the drama more intense. Without giving anything specific away, let me simply say that if you fell in love with the original trilogy, but have found era two to be a step back from them, The Lost Metal is a book worthy of the title Mistborn, and a larger contribution to the story of the Cosmere than books 4–6 combined.

“To Kill a Mockingbird” (1960) by Harper Lee

Most of you will have already read this, so I’ll keep this one extra brief. This was one of the many books I shirked reading in school, and I’m happy I rectified the situation now. At once a powerful morality tale, a courtroom drama, and a captivating slice-of-life view of the Depression-era US South, To Kill a Mockingbird is one of those books everyone should read at least once.

Disappointing Reads

“Why Liberalism Failed” (2018) by Patrick J. Deneen

It’s difficult to know where to begin in evaluating this book. The thesis is deeply flawed. The premise is deeply flawed. The analysis is deeply flawed. And the proposed solutions are deeply flawed.

Deneen’s assertion, that liberalism has indeed “failed”, seems to rest almost entirely on the ill effects of consumerism, environmental problems, and the decline of family, religion, and other institutions. These he lays at the feet of liberalism. Like a 22-year-old reply guy, Deneen makes no real attempt to weigh the progress of the past several centuries against the problems that exist today, instead opting to use the existence of those problems as evidence of failure. But what does he mean by liberalism? He criticizes democratic values, but assures us he doesn’t mean liberal democracy. He criticizes commercialism, but he assures us he doesn't mean capitalism. He criticizes Enlightenment values, but so also claims he doesn’t mean civil liberties or human rights. In the end, the closest sense he conveys as to what he means is not actually liberalism, but the far narrower concept of “individualism”: centering the freedom of the individual over the community or state.

Deneen’s ideas for what to do about the “failure” of liberalism and the problems that exist are vague gestures about reinvigorating community life and traditionalist culture, utterly bereft of specifics (a recurring theme throughout). Upon finishing Why Liberalism Failed, I was left with the sense that this is a book about nothing, built on nothing, which argues for nothing.

“The Brothers Karamazov” (1880) by Fyodor Dostoevsky

Having read and loved Crime and Punishment (1866), I was taken aback by just how different The Brothers Karamazov is. Brothers is, at heart, a philosophical novel, even a theological one. The story of three very different brothers and their relationship with their depraved father takes a back seat to explorations of ideas about the existence of god, the foundations of morality, free will, and the contrasts between European Enlightenment thinking and traditional Russian culture. The problem is, using fiction as a means to explore ideas, as opposed to writing straight-up nonfiction, only really works if the story is interesting, and The Brothers Karamazov simply wasn’t.

Reading through this bloated narrative, I suspected more than once that this novel must have been originally published in serial form (I was correct). Nothing else explained why Dostoevsky routinely took 10 pages to communicate two paragraph’s worth of content unless he was being paid to drag it out. The story was so bogged down with digressions and the dialogue so laden with repetitive prattling that the philosophy — which wasn’t exactly groundbreaking: “atheism bad” (I’m being reductive and a bit petulant, but I think I’ve earned it) — was drowned out. The book was not wholly without its moments, namely the latter portion involving the trial, but the kernels of genuine interest are few and far between. 100 pages could be trimmed from this book without removing a single story element, conversation, or thematically relevant discussion — and it would still feel too long.

“Too Much Information: Understanding What You Don’t Want to Know” (2020) by Cass Susntein

For a relatively short book on a topic of universal importance, Too Much Information seemed to drag on far beyond its page count. 90 percent of its insights are contained in the introduction and first chapter; the final 10 percent is scraped and stretched across all the remaining sections in ways that feel repetitive and, at points, irrelevant. At a sentence level, the book is competently written. Sunstein knows his stuff, and I immensely enjoyed his prior book, co-authored with Richard Thaler, Nudge (2008). But here he takes the reader around and around and leaves them with few concrete takeaways wondering why they bothered. The answer to this book’s subtitle is the book itself. I can’t recommend reading Too Much Information in its entirety. Read the first tenth of it and move on.

“The Data Detective: Ten Easy Rules to Make Sense of Statistics” (2021) by Tim Harford

It’s not entirely clear who this was written for. The kind of reader interested in a book about statistics is a self-selected group hungry for data, discussions of polling/research methodologies, and yes, some light mathematics. The Data Detective does not slake that hunger. It’s mostly heavily padded fluff and storytelling.

Harford opens with a truly outstanding introduction in which he contrasts his project and vision with Darrell Huff’s famous How to Lie with Statistics (1954), setting the rest of the book up to be a more complete picture of the data landscape and how to navigate it. What follows are the sorts of vague precepts that every person who picks this title up will already know, filled in with human interest stories. It’s as though The Data Detective was written in an attempt to be engaging to the average person with no interest in statistics or social science, forgetting that such people would never read this in a thousand years — and neglecting the actual audience that will.

I figured that while I’m sharing my year in reading, I might as well share my year in Substack writing. Here are the top ten most popular essays of 2023 as measured by traffic and engagement.

#10

#9

#8

#7

#6

#5

#4

#3

#2

#1

See you all next year!

See also: “2022: My Year in Books”

“2021: My Compelling and Rich Year in Books”

Subscribe now and never miss a new post. You can also support the work on Patreon. Please consider sharing this article on your social networks, and hit the like button so more people can discover it. You can reach me at @AmericnDreaming on Twitter, or at AmericanDreaming08@Gmail.com.

Nine Nasty Words by McWhorter

Caste by Wilkerson

Honestly...the Bad Nana series by Henn. If you're gonna spend a half hour every night reading with a kiddo, it's really well done for children's books.