Everything You Know About History Is Wrong: Part V — Food Edition

Debunking common historical food myths.

Everything You Know About History Is Wrong is a series I created in 2022 to explore widely believed historical myths in collaboration with all of American Dreaming’s contributors. The first four installments examined a broad range of topics, from ancient Egypt, to the Roman Empire, to the Napoleonic era, to the US Civil War, and up through events in the 1990s. Of all the entries I contributed, the one I had the most fun researching and writing was about Marco Polo and the origin of pasta. In this edition, I’m going solo with a full menu of myths about culinary and food-related history. Dig in and enjoy.

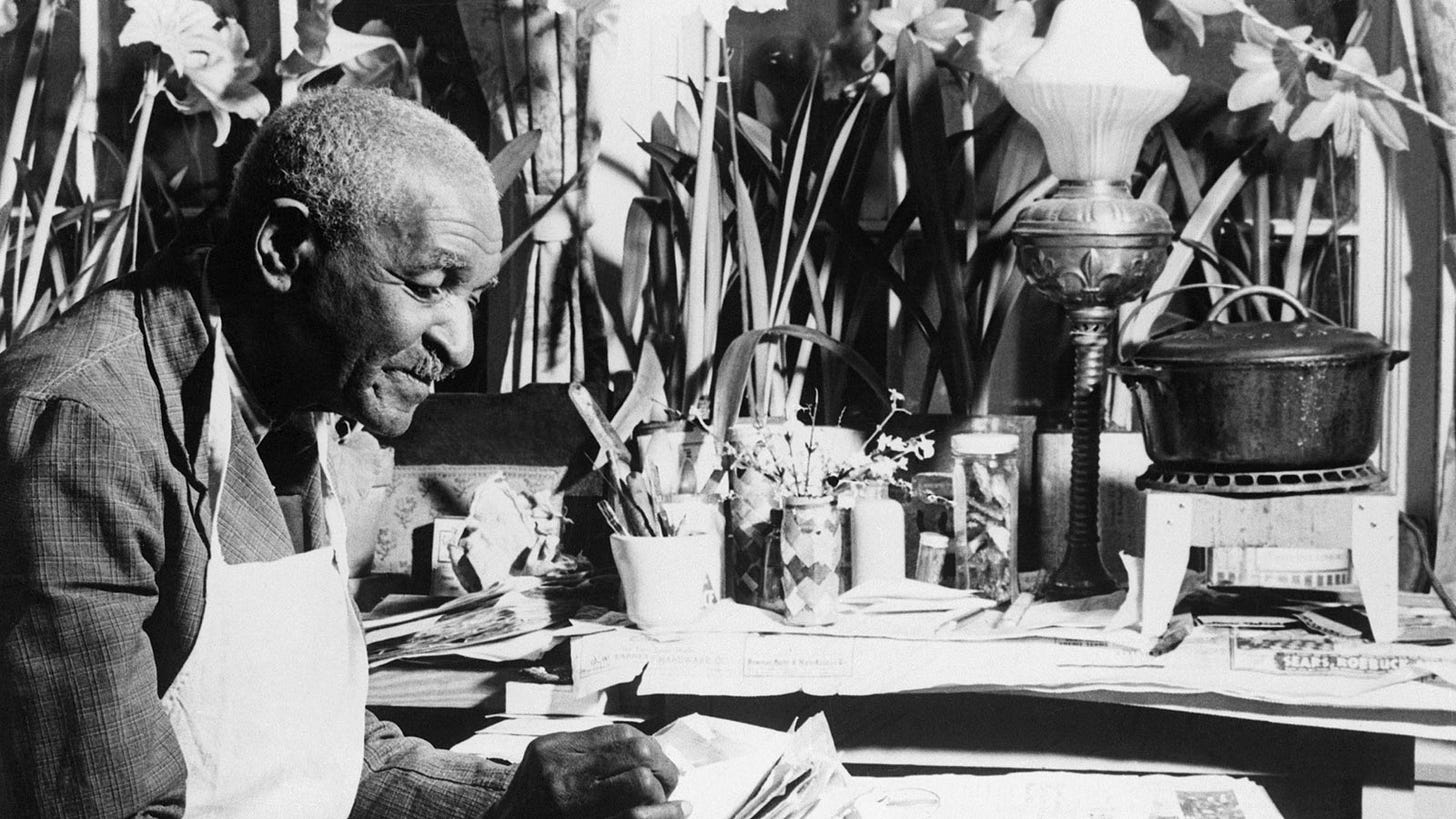

Myth: George Washington Carver invented peanut butter

George Washington Carver was a man of incredible accomplishment. Born into slavery in antebellum Missouri, Carver, fascinated with plants from a young age, went on to become an agricultural chemist, agronomist, and famous food innovator. He spent decades teaching about agriculture, often going out of his way to ensure that his courses and lessons could reach those most in need. Carver created the Jesup Wagon, a classroom on wheels that traveled the American countryside educating farmers about different crops and better agricultural techniques. As a pioneering advocate of emerging practices like soil conservation and crop rotation, his efforts helped save many Southern farmers from ruin in the late-19th and early-20th centuries.

Carver figured out how to turn soybeans into paints and stains, invented 118 products (both foods and non-foods) from sweet potatoes, and developed another 300 from peanuts alone. According to the US Department of Agriculture, “Among Carver’s many synthetic discoveries: adhesives, axle grease, bleach, chili sauce, creosote, dyes, flour, instant coffee, shoe polish, shaving cream, vanishing cream, wood stains and fillers, insulating board, linoleum, meat tenderizer, metal polish, milk flakes, soil conditioner, and Worcestershire sauce.” His bottomless bag of tricks and discoveries for how to eat and use peanuts earned him the nickname the “Peanut Man.” As peanut butter rose in popularity in the 20th century, the Peanut Man and peanut butter became inextricably linked, but of George Washington Carver’s myriad contributions to food, inventing peanut butter wasn’t one of them.

Peanuts are native to South America, with peanut fossils dating back at least 8,500 years. The earliest known version of peanut butter was found among the Incas between 1200 and 1533 CE,1 where peanuts were roasted and ground into a sort of paste. In 1884, the Canadian chemist Marcellus Gilmore Edson was issued a US patent to create a peanut paste of his own, processed with heat to create a product he called “peanut candy” — still not quite the same as the peanut butter we eat today, but more recognizable than what the Incas made. It was John Harvey Kellogg — the cereal guy, and a Seventh-Day Adventist vegetarian — who developed modern peanut butter in 1895 to be a healthy alternative to eating meat.

George Washington Carver was an amazingly prolific, ingenious, generous, barrier-shattering innovator who deserves to be celebrated for what he did — not what he didn’t.

Myth: Croissants were invented in France, or in celebration of the Ottoman Empire’s defeat in the Battle of Vienna

No country has been more influential on global culinary arts than France. Half the techniques, recipes, cookware, and terminology people use around the world stem from or have been influenced by French creations, French improvements, and, yes, French colonialism (e.g. modern Vietnamese cuisine). Imperialism sucks, but phở slaps. But one of France’s most iconic foods, the croissant, is layered with more myths than butter.

For starters, the croissant ain’t French in origin. According to the Institute of Culinary Education, croissants originated in Austria as a half-moon-shaped roll made with copious amounts of butter or lard called a kipferl or kipfel. Records indicate that kipferls go back to at least the 13th century. As Smithsonian Magazine’s Amanda Fiegl writes, “As recently as the 19th century, the French viewed the croissant as a foreign novelty, sold only in special Viennese bakeries in the pricier parts of Paris.” The croissant was inspired by the kipferl and perfected by the French, who upped the flakiness with a laminated yeast dough and even more butter — just don’t say this in front of any Austrians.

Another legend has it that Marie Antoinette, who was born in Austria, introduced the kipferl to the French court because she missed the food of her homeland, but there’s no evidence for this. The evidence we do have shows that Austrian businessman August Zang popularized kipferls in Paris in 1839, and the first French version of the croissant was officially recorded in 1915 by Sylvain Claudius Goy. Over the course of the 20th century, croissants became fixtures in everyday French eating, and gained worldwide recognition.

One more myth surrounding the origin of the kipferl/croissant claims that the pastry was invented in celebration of the defeat of the Ottomans in the Battle of Vienna in 1683, with its crescent shape designed to resemble the moon on the Ottoman flag. Since we know the roll is centuries older than this battle, we can safely say that this, too, is a myth.

Personally, I’ve never seen what all the fuss is about when it comes to croissants, but the number of myths surrounding a food’s history is usually a pretty good indicator that it’s reached the highest echelons of popularity.

Myth: MSG is harmful for health

One of those zombie lies that just won’t die despite being riddled with fact-checking bullets is that monosodium glutamate, the flavor-enhancing food additive commonly abbreviated as MSG, is particularly harmful and even dangerous to human health.2 On its face, this seems a purely health-related matter, however there is an important historical element to it. First, let’s address the health claims.

One systematic review of the medical literature after the next has shown that there’s no real problem with MSG. A 2017 review in the World Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences noted that “MSG is one of the most intensely studied food ingredients in the food supply and has been found safe.” Another 2019 systematic review in Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety concluded, “Critical analysis of existing literature establishes that many of the reported negative health effects of MSG have little relevance for chronic human exposure and are poorly informative.”

The only real health risk of MSG is the sodium content (monosodium glutamate). While MSG contains only about a third of the sodium found in salt, making it a comparatively healthier flavor-enhancer, it still has a fair amount of sodium, something almost all people in developed countries eat too much of. If you would think it insane to boycott a Chinese restaurant because its menu doesn’t advertise “no salt”, you shouldn’t be doing so because it doesn’t say “no MSG.” But where did MSG’s undeservedly bad rap come from?

MSG was first discovered by the Japanese Chemist Kikunae Ikeda in 1908 when he extracted it from kombu, an edible seaweed. By the 1950s, it had become a commonly used ingredient in processed foods the world over. But in the 60s, consumers began to scrutinize food additives, and a single complaint caught fire. As the food and health reporter Anna Maria Barry-Jester put it in FiveThirtyEight:

“In 1968, the New England Journal of Medicine published a letter from a doctor complaining about radiating pain in his arms, weakness, and heart palpitations after eating at Chinese restaurants. He mused that cooking wine, MSG, or excessive salt might be to blame. Reader responses poured in with similar complaints, and scientists jumped to research the phenomenon. ‘Chinese Restaurant Syndrome’ was born.”3

Of course, this letter was speculative, entirely anecdotal, and not a scientific study of any kind. But once it began to spread like wildfire, the fact that it was penned by a doctor and published in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine lent it an air of authority, even though it was simply a glorified reader response letter. A series of flawed and later debunked studies came out in the years following which muddied the issue further. All of this occurred after 1965, when the US dramatically opened up immigration from Asian countries, among others. The wish to connect this supposedly toxic ingredient with Asian immigrants played an undeniable role in the degree to which MSG became stigmatized.

The sad irony is that those who most fear MSG to this day tend to be politically progressive “natural” food advocates — the kinds of people who still mask in public and punctuate commands to “Believe. The. Science” with clap emojis. But their animus is unscientific and rooted in xenophobia.

Myth: Tang was invented by NASA, for NASA, or as a result of space race technologies

NASA and the space race produced a number of spin-off technologies with applications that help plenty of people down here on Earth, such as memory foam, the computer mouse, artificial limbs, freeze drying, scratch-resistant lenses, wireless headphones, and more. But, contrary to popular belief, Tang, the powdered orange-flavored drink mix, wasn’t one of them.

In his book, Salt Sugar Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us (2013), Michael Moss tells the tale of Tang. In 1956, Al Clausi, a food scientist at General Foods,4 figured out how to create a synthetic orange juice-like powder fortified with a comparable amount of vitamin C to the real thing. Two years later, Tang hit the shelves. When prepared as directed, Tang had only a bit more sugar than real juice, but since the product was a powder, consumers could — and usually did — add somewhat more per glass than the suggested serving size. It became a high-sugar soft drink that folks rationalized as healthy because it contained vitamin C. Then, as Moss writes:

“NASA, the space program, needed a drink that would add little bulk to the digestion, given the toilet constraints in space. Real orange juice had too much bulky fiber in its pulp. Tang, however, was perfect — what technologists call a ‘low-residue’ food. When NASA heard about Tang, Clausi instructed a colleague: ‘Tell NASA we’re honored to be of service, and we’ll supply whatever they need — free of charge.’ On February 20, 1962, John Glenn returned from his triple orbit around the earth and told reporters that the only good thing about the food aboard his spacecraft was the Tang. With that endorsement, sales exploded.”

Tang gained a reputation as a futuristic “astronaut food”, and from there, it was only a matter of time before it joined the ranks of velcro and teflon as apocryphal innovations or spin-offs from space technology. In reality, it was (and still is) little more than orange Kool-Aid that got some awesome PR from an astronaut who used it to wash down freeze-dried space food. NASA should be embarrassed at the free press they gave to Tang, but at least they can take solace in the fact they didn’t invent the stuff.

Myth: Sushi originated in Japan

As its popularity exploded across the world over the past few decades, sushi has become perhaps Japan’s most globally recognized and celebrated dish. But the history of sushi is a long and murky path that takes us beyond the shores of Japan.

The earliest proto-sushi, called “narezushi” (“matured sushi”), originated in China sometime between the 5th and 3rd centuries BCE. It involved pickling and fermenting fish with rice, vinegar, wine, and salt as a way of preserving it. This practice made the trip across the pond to Japan sometime between 710 and 794 CE. Over the centuries, changes and innovations in cooking and preparation techniques sped up the fermentation process. During the Edo period (1603–1868), people began using vinegar separately to directly flavor the fish, allowing it to be eaten right away while retaining that sour fermented taste. They called it “hayazushi” (“quick sushi”). By 1820, the art of sushi making had evolved to its modern form, “nigirizushi” (hand-rolled sushi) made by a chef named Yohei Hanaya.

What began as a method for food preservation progressed through the years from a product that was slowly fermented and pickled to a freshly prepared dish that retained a similar flavor profile through the use of seasoned vinegar and condiments. To set what we now think of as sushi side by side with the very earliest Chinese narezushi, they seem like two entirely separate species of food with nothing in common. And yet they share a gastronomical lineage reflected in their names. So no, Japan did not invent the original sushi, but they made it infinitely better, faster, and more popular — and at the end of the day, that’s actually the far more impressive accomplishment. Itadakimasu!

See also: “Everything You Know About History Is Wrong” Part I, Part II, Part III, and Part IV

Subscribe now and never miss a new post. You can also support the work on Patreon. Please consider sharing this article on your social networks, and hit the like button so more people can discover it. You can reach me at @AmericnDreaming on Twitter, or at AmericanDreaming08@Gmail.com.

The Aztecs are sometimes also offered as early creators of peanut butter, but I could not find sufficient evidence for this claim.

Of the five flavors humans can taste, MSG enhances savoriness, also known by the Japanese name of “umami.” (The other four flavors are sweet, salty, sour, and bitter. Spiciness is not actually a flavor detected by taste buds, but rather a mouth sensation.) Savoriness comes primarily from glutamic acid (monosodium glutamate), the most abundant amino acid found naturally occurring in food and within the human body.

Cultures around the world have been using glutamate-rich foods to enhance the flavors of dishes for ages. Italians use anchovies and aged Parmigiano Reggiano cheese. Throughout Asia, people use mushrooms, fish sauce, and fermented pastes such as miso, doubanjiang, and gochujang. And pretty much everyone at this point cooks with soy sauce, tomato paste, and garlic. Food manufacturers skirt the notice of misinformed but health-conscious consumers with “no MSG” ingredients like yeast extract and mushroom extract that perform the same savory-boosting function because they share the same active ingredient — glutamic acid. MSG is simply the chemically pure essence of all of these ingredients — it’s the Walter White “blue sky” of umami, or what comedian Nigel Ng’s character Uncle Roger calls the “king of flavor” and “salt on crack.”

The aforementioned 2017 systematic review: “A popular belief is that large doses of MSG can cause headaches and other feelings of discomfort, known as ‘Chinese Restaurant Syndrome’ (CRS), but double-blind tests fail to find evidence of such a reaction.”

And the 2019 systematic review: “Reports on MSG hypersensitivity, also known as ‘Chinese restaurant syndrome’, or links of its use to increased pain sensitivity and atopic dermatitis were found to have little supporting evidence.”

General Foods was acquired by Philip Morris (the tobacco company) in 1985 and merged with Kraft in 1990.