The Hebrew Hammer: The Hank Greenberg Story

With Nazism raging overseas and hatred brewing at home, American Jews needed someone to be the symbol of their strength. Hank Greenberg became their champion.

This post is by contributor Jacob Bielecki.

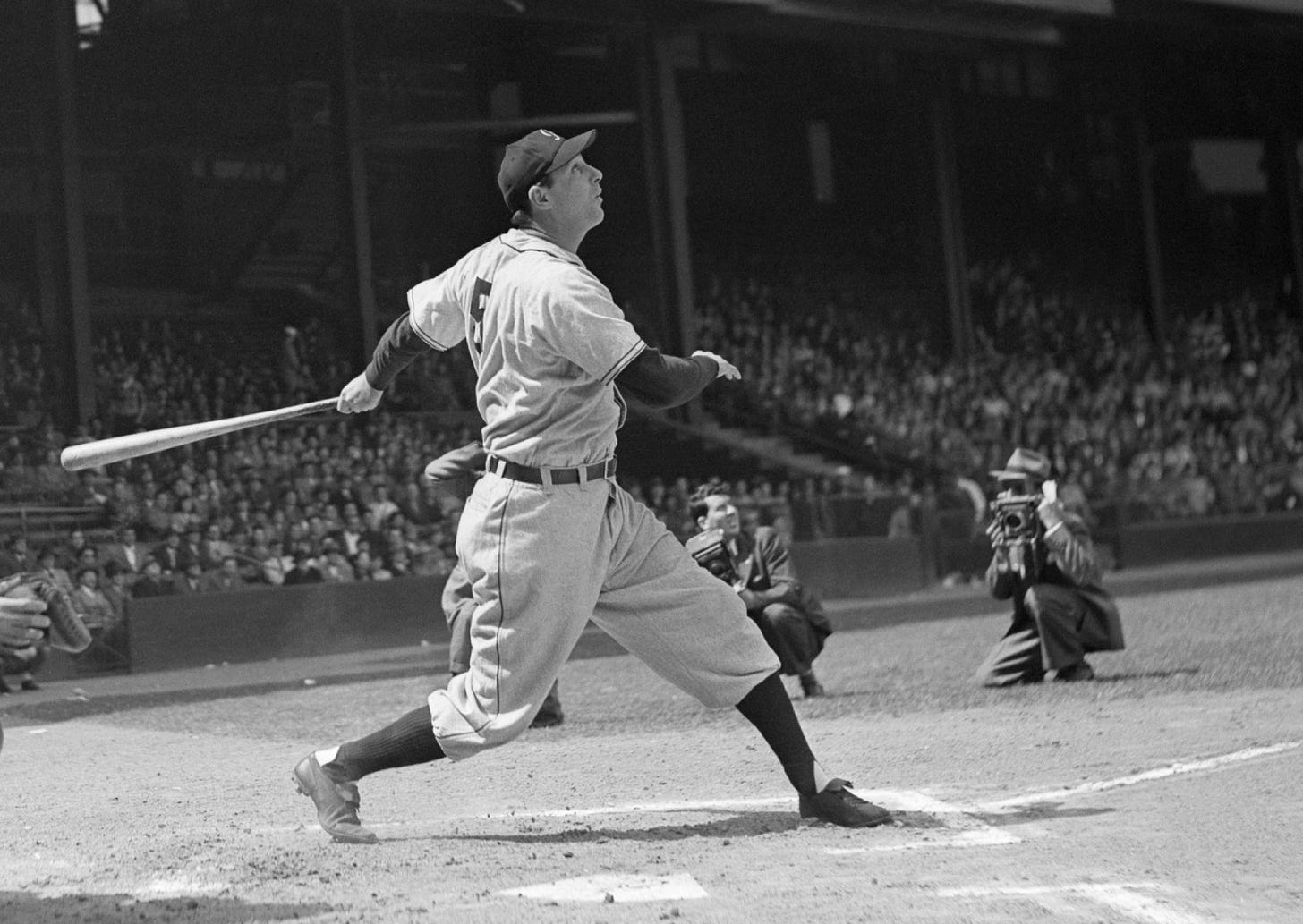

As the 1934 season drew to a close, Detroit Tigers first baseman Hank Greenberg found himself in a dilemma. It was only his second year in the big leagues, but Greenberg had already established himself as one of baseball’s premiere sluggers and the world’s first Jewish sports superstar. The Detroit Tigers had not won a pennant since 1909, and they had never won a World Series. As the autumn breeze began blowing into Detroit in September, the Tigers were only four games ahead of the New York Yankees in the American League pennant race. Baseball was an unforgiving sport in those days. There were no playoffs, only the World Series between the American League and National League teams who finished the regular season in first place in their respective leagues. The Tigers desperately needed Greenberg’s bat if they were going to clinch the pennant. However, Greenberg was torn between his commitment to a religion he had always been ambivalent about and his commitment to his team.

September 10 was Rosh Hashanah and September 19 was Yom Kippur, the two most important holidays in Judaism. Fans and the press speculated in the lead-up to these holidays whether Greenberg would play or not. When Greenberg announced that he would not play on the holidays, it caused nationwide controversy around the US. American Jews and rabbis from all over the country who had been inspired by Greenberg smashing anti-Jewish stereotypes with his bat were now debating if he should honor the holiest of days or if he should lead the Tigers to their first pennant in 25 years. Greenberg was flooded with mail offering advice as to what he should do.

Among the rabbis who offered their opinions was a Reform rabbi who stated that it was perfectly fine for Greenberg to play, citing that the Talmud references children playing in Jerusalem streets during holidays.1 Orthodox rabbi Yosef Thumim of the Beth Abraham Congregation in Detroit argued that Greenberg could play on Rosh Hashanah so long as Orthodox Jews did not attend, smoking was banned in the stadium, and all the concessions were kosher. These demands were obviously impossible to fulfill. The contradictory advice from rabbis who spoke through the media or communicated with Greenberg privately only served to confuse him. Greenberg consulted Tigers’ manager and catcher Mickey Cochrane, who told him that while he wanted him in the field, he would respect his decision no matter what. Greenberg’s father David ultimately had the most influence over his decision. After discussing the matter together, Greenberg compromised and announced that he would play on Rosh Hashanah but sit out Yom Kippur.

On the morning of Rosh Hashanah, the First of the High Holy Days, Hank Greenberg went to the Congregation Shaare Zedek, a Conservative synagogue then located in the northwest section of Detroit. That afternoon, he arrived at Navin Field (later known as Tiger Stadium) for that day’s game against the Boston Red Sox. The Detroit Tigers won 2-1, powered by two home runs from Greenberg, the second of which came thrillingly in the bottom of the ninth inning. It was a great victory for the Detroit Tigers, but an even greater one for American Jews.

The Tigers lost on Yom Kippur without their star first baseman in the lineup, but the pennant race had been sealed by that point, and when Greenberg walked through the Congregation Shaare Zedek’s doors he was given a hero’s welcome by the congregants. For the first time, Greenberg realized just how much his success meant not only to Detroit’s Jewish community, but to Jews throughout the US. The decision to play or not play on the holiest of Jewish holidays was a tremendous challenge for a newly famous 23-year-old. Yet Greenberg faced it with the same humility and grace he brought to every area of his life, whether he was dominating baseball, being showered with anti-Semitic jeers, or serving his country in World War II.

Hank Greenberg was born to Orthodox Jewish Romanian immigrants Sarah and David Greenberg in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village on New Year’s Day, 1911. The Greenberg family was well off for that era, owning a cloth shrinking plant in the city. When Greenberg was six years old, the family moved to the Bronx, where his athletic talent began to blossom and he became a star athlete for James Monroe High School in a variety of sports, including basketball, track and field, and soccer. His favorite sport, however, was baseball, and young Hank spent countless hours at the park next door practicing his swing and shagging balls.

Despite his athletic prowess, Greenberg was uncomfortable in his skin. An unusually tall kid, he towered above his peers and was somewhat uncoordinated because he hadn’t grown used to his large frame and flat feet. Although Greenberg’s dexterity would never be described as graceful, he eventually learned to utilize his size and strength to his advantage. As Hank’s dream of becoming a ball player took shape, David and Sarah Greenberg were dismayed by their son’s lack of interest either in the family business or in going to college. In their view, baseball players were ne’er-do-wells and bums.

New York City was home not only to America’s largest Jewish population (then as today), but also to three Major League Baseball teams at the time, and it wasn’t long before they heard of Hank Greenberg’s talent. The management for the New York Yankees, New York Giants, and Brooklyn Dodgers had been looking for a Jewish player who could bring in Jewish fans to the ballpark. Yet none of the New York teams signed Greenberg. The Dodgers never expressed any interest and Giants Manager John McGraw was unimpressed with Greenberg during his informal tryout with the team. The Washington Senators (now the Minnesota Twins) wanted to sign Greenberg, but he passed on their offer because they already had an everyday first baseman in Joe Judge.

The New York Yankees seemed like a natural fit on the surface. After all, Greenberg grew up in the Bronx where the Yankees played, but the team already had a superstar first baseman in Lou Gehrig. That didn’t stop Yankees scout Paul Krichell from pursuing Greenberg. Krichell met with Hank’s parents several times and although they liked him, they still weren’t sold on their son’s Major League aspirations. In a last-ditch effort to convince Greenberg to sign with the team, Krichell brought Hank and David Greenberg to the Yankees’ last home game of the 1929 season. During the game, Hank’s eyes were drawn to Lou Gehrig. Krichell leaned close and told Greenberg that Gehrig was past his prime and that Hank would only need to wait a couple years to take his place if he signed with the Yankees. However, even at 18 years old, Greenberg was almost always the smartest person in the room and possessed a foresight that is rare among professional athletes. He’d grown up watching Lou Gehrig play at Yankee Stadium, listened to his exploits on the radio, and read about him in the papers. Greenberg knew Gehrig had plenty of great years still left to play (Gehrig retired in 1939) and opted not to sign with the Yankees.

The Detroit Tigers were the only team left interested in Greenberg and he signed a contract to play for their minor league club and received a $9,000 bonus ($171,199 in 2025 dollars).

From 1930 to 1933, Greenberg worked his way through the Detroit Tigers’ farm system. He did play in one major league game at the end of the 1930 season, but the Tigers organization was patient with Greenberg and took their time developing and nurturing his talents. While playing in the minors one day, a Southern player approached Greenberg and said that he couldn’t believe the first baseman was Jewish. When Greenberg asked him why, the player responded that he’d heard Jews have horns on their heads.

Hank Greenberg’s rookie year of 1933 came during a pivotal moment in history. On February 28, German President Paul von Hindenburg issued the Reichstag Fire Decree at the behest of Chancellor Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party. The decree, which was issued in response to the Reichstag Fire the day before, gave the Nazi government the power to arrest anyone without charge, eliminate political parties, and censor the press. The decree also gave the Nazis the power to overrule state and local laws and eliminate local governments. On March 10, the Dachau Concentration Camp opened north of Munich. Five days later, Greenberg played his first Spring Training game for the Detroit Tigers in San Antonio, Texas. On March 23, the Enabling Act was passed by the Reichstag giving Adolf Hitler the power to enact and enforce laws without the Reichstag or von Hindenburg’s involvement. One month later, Hank Greenberg made his debut as the Detroit Tigers’ starting first baseman.

Detroit’s History of Anti-Semitism

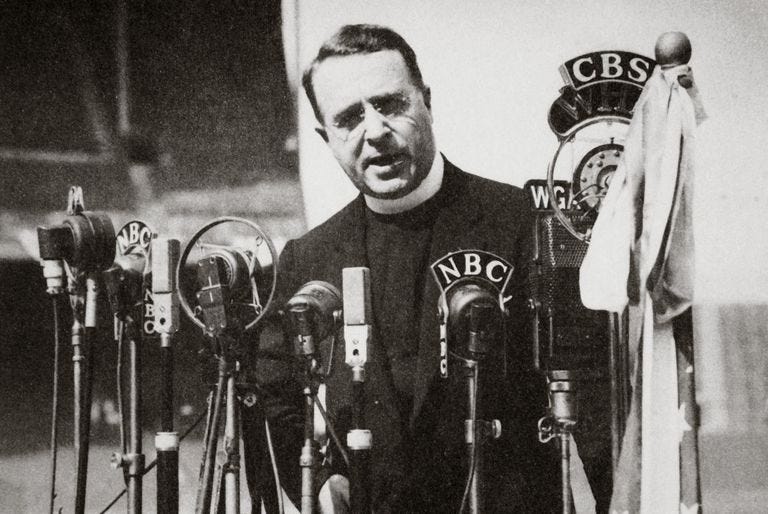

Anti-Semitism wasn’t just boiling over in Europe; it was spreading in the United States as well, and Detroit, Michigan was its beating heart, led by Father Charles Coughlin. A Catholic priest based out of nearby Royal Oak, Father Coughlin’s radio show, “The Golden Hour of the Little Flower”, aired every Sunday on Detroit’s WJR station. When the show started in 1926, Father Coughlin was only broadcasting the same homilies he gave at his Shrine of the Little Flower church. But the onset of the Great Depression sparked a change in programming and Father Coughlin’s sermons became increasingly political.

During his first political broadcasts, Father Coughlin targeted communists, but he was only just getting started naming his enemies. President Herbert Hoover, Wall Street, and capitalism itself were also targets of Coughlin’s wrath. The American people, beaten down by the Depression and looking for someone to blame, couldn’t get enough of Father Coughlin’s show, and his listenership skyrocketed as the program was syndicated to stations around the country. According to the New York Times, an estimated 90 million Americans were tuning into Father Coughlin’s program every week. To put that in perspective, in 1936, the United States’ population was 128 million, meaning that if the NYT’s estimation is correct, 70 percent of Americans regularly listened to Father Coughlin’s show at the peak of his popularity.

By 1932, Father Coughlin’s massive listenership meant his endorsement would be pivotal to any aspiring politician and he became then-candidate Franklin Roosevelt’s most famous supporter. Although Roosevelt met with Father Coughlin to court his support, FDR did not listen to any of Coughlin’s policy suggestions and their relationship soured. By 1935, as Hank Greenberg and the Detroit Tigers embarked on the campaign which would finally bring the Motor City its first World Series championship, Father Coughlin had become one of President Roosevelt’s biggest critics. He formed his own political party, the National Union for Social Justice, and labor unions joined communists and Wall Street as the villains of his diatribes.

Father Coughlin also began preaching the need for the United States to have an isolationist foreign policy. He started quoting Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini and praising their policies. It wasn’t long before members of the National Union for Social Justice were painting swastikas on Jewish businesses and assaulting Jews throughout the country. During his first broadcast after Kristallnacht, Father Coughlin said the Jews brought it on themselves. Eventually, Father Coughlin’s radicalism caught up with him. His political party dissolved amid federal investigations after its crushing electoral defeat. His radio program was forced off the air by the Catholic Church after the Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor, when he alleged that World War II was a conspiracy concocted by the British, President Roosevelt, and the Jews. Father Coughlin retired from public life. In an interview two years before his death in 1979, Father Coughlin was unrepentant for the statements he made on his program.

Henry Ford was one of the most powerful men in the US during the first half of the 20th Century. He was also America’s most powerful anti-Semite. Ford believed that the Jews were responsible for all that was wrong with the country. He blamed Jews for nearly everything, from getting America involved in World War I, to the 1919 race riots that swept the nation, to the poor state of the Navy. In 1918, Ford, a Michigan native, purchased his hometown newspaper, the Dearborn Independent. Within two years, the weekly paper published “The International Jew: The World’s Problem.” The article stated, “There is apparently in the world today a central financial force which is playing a vast and closely organized game with the world for its table and universal control for its stakes.” Similar articles were printed every week for the next two years, and Henry Ford used his financial muscle to widely distribute the publication. The newspaper was sold at Ford dealerships, and a free copy came with the purchase of every Model T. The Dearborn Independent had a circulation of 900,000 at its peak in 1926.

The Dearborn Independent’s anti-Semitic turn coincided with the Black Sox Scandal, when members of the Chicago White Sox conspired with gamblers to throw the World Series. The scheme was bankrolled by New York City racketeer Arnold Rothstein, though he was never charged in connection to the conspiracy. This was all the evidence the Dearborn Independent needed to blame the Black Sox Scandal on all Jews, including White Sox general manager Harry Grabiner, who had nothing to do with the fix. Henry Ford himself said during this period, “If fans wish to know the trouble with American baseball, they have it in three words — too much Jew.”

Henry Ford collected the anti-Semitic articles printed in the Dearborn Independent and published them in pamphlet form as The International Jew, released in four parts between 1920 and 1922. Ford chose not to copyright any of the content, wanting his message to be heard far and wide and for other anti-Semites to publish and distribute it without charge. The International Jew sold over two million copies in its first two years. The publication was translated into 16 languages and sold across three continents. It found an audience with Adolf Hitler, who became one of Henry Ford’s greatest admirers. Hitler praised Ford in Mein Kampf (1925) writing, “Ford, [who], to [the Jews’] fury, still maintains full independence […] from the controlling masters of the producers in a nation of one hundred and twenty millions.” Hitler even had a portrait of Ford in his office where he kept a copy of The International Jew in his desk.

During a March 1923 interview with the Chicago Tribune, Hitler addressed the rumors of a Henry Ford Presidential run by saying, “I wish I could send some of my shock troops to Chicago and other big American cities to help in the elections. We look on Heinrich Ford as the leader of the growing fascist movement in America. Germans admire particularly his anti-Jewish policy which is the Bavarian fascist platform.”

On July 30, 1938, during the middle of Hank Greenberg’s quest to break Babe Ruth’s record for home runs in a season, Henry Ford was granted the Grand Cross of the Supreme Order of the German Eagle, the highest award given by Nazi Germany to foreigners, for his 75th birthday. The award was given to Ford by Karl Kapp, Germany’s consul to Cleveland, and Fritz Heller, the German consul to Detroit. The Nazis invaded Poland a year later.

The Hebrew Hammer comes to Detroit

Jews had already succeeded in America despite the racism they endured by the time Hank Greenberg began torching American League pitching. There were Jewish scientists like Eugene Wigner and intellectuals like Lionel Trilling. Jewish immigrants like Samuel Goldwyn and the Warner Bros. created the movie industry as we know it. However, the threat of fascism at home and abroad required a physical response. American Jews, especially Detroit’s Jews, needed someone to be the symbol of their strength. Hank Greenberg became their champion.

Among fans and admirers, the power-hitting Greenberg earned the monikers “Hammerin’ Hank” and the “Hebrew Hammer.” Haters had a different set of names. During every game of his career, Greenberg was called slurs like “kike”, “sheenie”, “Jew bastard”, “pants presser”, “mockey”, or “Christ killer” by opposing players or the crowd. Sometimes Greenberg ignored the abuse and got on with the at bat. At other times, he stood up for himself. After overhearing a Yankees player shout an anti-Semitic slur, Greenberg stepped out of the batter’s box, stormed to the New York dugout and challenged whoever shouted at him to show his face. Ultimately, there was little Greenberg could do but play on. He endured the jeers and fell just three home runs short of breaking Babe Ruth’s single-season record of 60 home runs in 1938. It was as though with every home run he hit, Hank Greenberg did more than just put runs on the scoreboard — in the eyes of American Jews, he struck a blow against Father Coughlin, Henry Ford, and Adolf Hitler.

Hank Greenberg’s style of play was not pretty to look at, but it was effective. At six feet four inches tall and 210 pounds, Greenberg would still be one of the bigger players in today’s game. In the 1930s and ‘40s, he was practically a giant. Despite his flat fleet, Greenberg was an excellent baserunner and his 63 doubles in 1934 are fourth all time on the single season doubles list. Although the Detroit Tigers lost to the St. Louis Cardinals in the 1934 World Series, they came roaring back in 1935 to defeat the Chicago Cubs for their first championship in franchise history. Greenberg won the MVP award, with an American League-best 36 home runs and an MLB-leading 168 runs batted in (RBIs). In 1937, Greenberg led the league in RBIs again, driving in an astounding 184 runs, just two shy of breaking Lou Gehrig’s American League record.

Although he was an above-average first baseman, Tigers management asked that he move to left field to accommodate Rudy York, a great hitter whose defensive liabilities could be sheltered at first base. Knowing that York’s bat would be pivotal to the team’s success, Greenberg agreed to change positions and practiced extensively in the outfield during the 1940 Spring Training season to master left field. Greenberg won the MVP that year and the Tigers won another pennant.

Greenberg Goes to War

After the 1940 season, Hank Greenberg became the first Major League Baseball player to register for the draft. The day before he began his service on May 6, 1941, he hit two home runs to help the Detroit Tigers beat the New York Yankees at Tiger Stadium. Baseball fans wouldn’t see Greenberg take the field again for three and a half years. “If there’s any last message to be given to the public, let it be that I’m going to be a good soldier,” Greenberg told The Sporting News.

Serving in the Army meant that Greenberg took a $49,000 pay cut ($1,058,903 in 2025 dollars). He initially served at Fort Custer in Battle Creek, Michigan in the Army’s Fifth Division, Second Infantry Anti-Tank Company. During his first day at boot camp, the sergeant spouted anti-Semitic slurs, saying, “I don’t want no Goldbergs and no Cohns in my unit.” The Hebrew Hammer raised his hand and said, “My name is Greenberg.” The sergeant took one look at the 6'4"giant and replied, “I didn’t say anything about Greenbergs.”

Hank Greenberg was discharged after only a few months when Congress passed a law stating that anyone over the age of 28 be released from their service obligations. He was formally discharged on December 5, 1941, two days before the attacks on Pearl Harbor. On February 1, 1942, Greenberg re-enlisted and was commissioned as a sergeant in the Army Air Forces and then promoted to first lieutenant after completing officers’ training school.

Initially, Greenberg was a physical education instructor. In February 1944, Greenberg was promoted to captain and requested to serve overseas. He was transferred to the China Burma India (CBI) theater where he served for six months scouting locations for B-29 Bomber bases. According to Greenberg’s son Steve, his father had to fly over the Himalayan Mountains during some of his scouting missions and the turbulence from the plane resulted in several close calls for Greenberg and his crew. Greenberg was later transferred to New York and by the end of 1944 he was stationed in Virginia and placed on the inactive duty list. He was discharged on June 14, 1945 after serving in the military for 47 months, longer than any of the 500 Major Leaguers who served during World War II.

When Hank Greenberg re-enlisted after Pearl Harbor, he was convinced that his baseball career was over. Yet, he knew doing his part to defeat the Axis was more important. Greenberg’s time in the armed forces had a profound effect on his worldview. Never a particularly observant Jew, Greenberg turned against organized religion entirely during his time serving in the war, coming to view it as a source of division and hatred in the world. Greenberg being the first player to enlist also meant that he was the first player to come back from the war. He didn’t disappoint. On July 1, 1945, 17 days after he was discharged, Greenberg hit a home run in his first game back in front of a sold-out crowd at Tiger Stadium. The Detroit Tigers would go on to defeat the Chicago Cubs in the World Series.

The following year, Greenberg led the league in home runs and RBIs again, but when his season got off to a sluggish start, he was booed by Detroit fans. Relations between Greenberg and Tigers management collapsed in the offseason due to a salary dispute. Greenberg, who was suffering from nagging injuries, elected to retire rather than take a pay cut, but before he could do that, the Tigers traded him to the Pittsburgh Pirates. Pirates owner John Galbreath convinced Greenberg to play for one more year, giving him a $100,000 salary and moving the left field wall at Forbes Field to accommodate his power hitting.

The Legacy of Hank Greenberg

Greenberg retired after the 1947 season. He became the general manager and part owner of the Cleveland Indians during the 1950s and later assumed the same roles for the Chicago White Sox later that decade. Greenberg finished his playing career with 1,628 hits, 331 home runs, and 1,274 RBIs. He led the American League in home runs and RBIs four times. Had it not been for World War II, he almost certainly would have hit 500 home runs and driven in nearly 1,800 RBIs, milestones that would have placed him with Hall of Famers like Ken Griffey Jr., Frank Robinson, his fellow Detroit Tigers first baseman Miguel Cabrera, and his contemporary Jimmie Foxx. Greenberg was a five-time All-Star, two-time MVP, and won two World Series Championships. He was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1956. His rift with the Detroit Tigers would last until June 12, 1983, when Greenberg and his former teammate, Hall-of-Fame second baseman Charlie Gehringer, had their numbers retired.

Hank Greenberg sacrificed his own ambitions for the greater good. He gave up the prime years of his playing career to serve America, even though his fellow citizens spat in his face. And although he is rightly considered among baseball’s all-time greats, Greenberg’s selflessness in the face of hatred and injustice is more important and worthy of remembrance than any award, honor, or statistic he achieved. More than that, the Hebrew Hammer always stood up for what was right.

Greenberg’s final year as a player was Jackie Robinson’s first. The hate Robinson encountered from the fans, opposing teams, and even his own teammates was even worse than the bigotry Greenberg confronted during his career. Robinson received letters threatening to kill him, his wife, and infant son. Hotels refused to host Robinson while welcoming his white teammates on the Dodgers. On May 15, 1947 Jackie Robinson played his first game against the Pittsburgh Pirates. Robinson beat out a bunt single and collided with Greenberg during the play. The following inning, the two met at first base and Hank asked Jackie if he was alright. After being assured that he was unhurt, Greenberg told Robinson, “Don’t pay any attention to these guys who are trying to make it hard for you. Stick in there. You’re doing fine. Keep your chin up.” After the game, Jackie Robinson told the New York Times, “Class tells. It sticks out all over Mr. Greenberg.”

See also: “Born in the U.S.A.: The Protest Song America Misheard”

Subscribe now and never miss a new post. You can also support the work on Patreon. Please consider sharing this article on your social networks, and hit the like button so more people can discover it. You can reach me at @AmericnDreaming on Twitter, @jamie-paul.bsky.social on Bluesky, or at AmericanDreaming08@Gmail.com.

The children in the cited passage may have referred to Roman children and not Jews, which suggests that the rabbi in question might have been willing to bend the rules for Greenberg.