The Free Will Debate Is Dead, but It Shambles On

What was once a cosmic question has been reduced to silly word games.

From the great thinkers of antiquity, to the sacred texts of nearly every religion, to the discourse of generations of philosophers, theologians, scholars, and artists, the debate over free will, like every other cosmic question, has raged for millennia. Over the past century, however, most of the participants in the free will debate have gradually coalesced around similar views. While the belief in absolute free will remains a popular article of faith for humanity at large, among those who actively engage the subject, the consensus appears to be that free will, as traditionally believed, does not exist. Among those who actually do the debating, the “debate” is mostly over. It’s been over for decades. And yet it shambles on, like a ghost in denial of its own demise, shifting from the question of whether free will truly exists to senseless and boring word games grounded not in a genuine pursuit of truth, but a misguided concern over implications.

The spectrum of thought on free will falls into three general camps. Libertarians believe that free will exists and that people have the capacity to make free and conscious decisions, undetermined by prior causes or natural laws.1 Determinists believe that human actions are determined by causes external to any conscious will and are thus not truly free.2 And compatibilists more or less agree with determinists, but try to redefine what free will means in order to say that humans still have it. More specifically, compatibilists shift the goalposts of free will from independence from causal influences (could one have chosen otherwise in an undetermined sense) to alignment with one’s internal desires, free from external coercion (was the choice made absent a proverbial gun to one’s head).

What’s mystifying is that for a question so central to human existence, there isn’t much opinion data about it. Unlike religion, belief in gods, evolution, souls, the afterlife, and the meaning of life, polls and surveys asking whether people believe in free will are few and far between. A 2019 study found that over 82 percent of Americans believed in free will, though when the researchers attempted to differentiate between libertarian free will and compatibilism, a majority of the respondents paradoxically agreed with both versions simultaneously. This confusion is emblematic of the general public’s views on free will. Another study from 2024 showed that ordinary people oscillate between different views of free will based in part on how much their emotions are activated, with greater emotional reactions linked to compatibilism. It should come as no surprise that most people feel they have free will, nor that such feelings represent the extent of their engagement with the subject.

Among academic philosophers, the 2020 PhilPapers Survey found something more remarkable: 18.8 percent believed in libertarian free will, 11.2 percent in determinism, and a resounding 59.1 percent in compatibilism. In other words, over 70 percent of philosophers acknowledge that free will, as the majority of humans throughout history have understood it, does not exist, but only 11 percent will admit it. And this is emblematic of the ditch in which the free will debate has become interminably mired in recent decades.

The default human intuition is to assume that because we feel like free agents, we therefore are. This is why libertarian free will is most common among people who haven't spent much time thinking about free will. But the evidence against that position is considerable, even overwhelming. When we trace the causal chain behind any action, thought, or decision, we encounter a galaxy of factors influencing and guiding us over which we have no conscious control in any given moment. We don’t choose our genes, upbringing, neurobiology, memories, or past experience. Nor do we choose our brain chemistry, knowledge, talents, abilities or disabilities, and available opportunities.

Indeed, even those factors to which one might ascribe human agency unavoidably fall prey to the same causal regress. For example, it might seem like I can choose whether or not to become skilled at chess. Of course, everyone acknowledges that this opportunity is constrained by things like intelligence and mental disability. But as long as one has the basic mental tools, as most people do, it would seem that they can choose to become at least moderately skilled at chess. And yet, when you sit down in front of a board to play an opponent, at that moment, your skill is either there or it is not.

I haven’t played a game of chess in over 20 years. If I were to play someone skilled, I cannot “will” my own nonexistent chess skills into being at that moment. But surely I could have chosen at some point in the past to have developed them. And yet, if I retrace the steps of my life, in every instance where I might have practiced chess but didn’t — usually because playing chess never even occurs to me — I cannot account for these decisions without recourse to more prior causes, themselves built upon further causes. Did I choose, in those countless moments, for chess not to occur to me? Did I choose, in those vanishingly rare instances when it did, to find the prospect unappealing?

When examined, we find that thoughts simply spring out of the void, disconnected from our conscious minds, which work overtime to generate an endless string of post-hoc rationalizations for the next thing we think or do. Anyone who has ever attempted to meditate can witness this process firsthand. Try not to think for 10 seconds, focusing only on your breath, and you will find that your mind has a mind of its own. Thoughts arise unbidden from the subconscious, the product of prior causes, including the thoughts indicating whether to act on those thoughts. To meditate is to become radically acquainted with the degree to which we are mere passengers in the vehicle we assumed we’d been driving. Determinists recognize this, even if they aren’t meditators. So do compatibilists, and yet, like a surgeon in a medical drama, they cling to the corpse, performing futile chest compressions on a patient who isn’t coming back while colleagues drag them away. He’s gone, Jim.

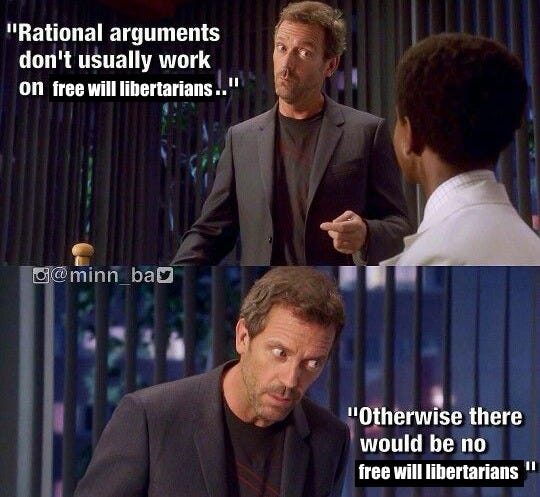

In the free will debate, there are very few libertarians. The reality is, to be interested enough in the question of free will to participate in the discourse requires a level of prior consideration that ends up turning most libertarians into determinists or compatibilists. So the debate, mostly between determinists and compatibilists, devolves into the the narcissism of small differences — a mind-numbing semantic squabble over what we call this thing happening inside our skulls, which we all agree isn’t really free will in the sense popularly believed. This dynamic isn’t unique to the subject of free will, either. The 20th century was a low point for Western philosophy, which moved away from its original ethos — finding what is true and/or good — and degenerated into endless deconstruction and linguistic analysis. Modern technology and the countless moral quandaries it presents have given philosophy back its sense of relevance, but free will hasn’t gotten the memo, in large part because it is an obsolete debate.

The question at the core of free will has always been “Are we truly the authors of our actions?” not “Well, I wanted to pick up the glass of juice, so I did, and no one was forcing me at knifepoint.” It’s a cheapening of the discourse. It’s Bill Clinton, caught red-handed with a White House intern, quibbling over the definition of “is.” Why does this excruciating and dishonest charade persist? Because, as Dennis Reynolds once said, of the “implication.”

I have trouble believing that very many people arrive at compatibilism motivated purely by a dogged pursuit of truth.3 To believe that would be to insult too many people’s intelligence. More likely, the desperation to salvage something upon which we can slap the label “free will” seems one born of utility, expedience, and worry, because determinism, from a certain point of view, threatens to upend society and sow chaos. This concern is understandable, though misguided.

First, let’s be very clear: whether or not determinism is socially harmful is a separate matter from whether it is true or false. And yet the prospect of social harm dominates the issue. What many fear is that a widespread abandonment of free will, which undergirds many of our religions, laws, norms, and institutions, will destroy the basis upon which cooperation, social contracts, justice systems, and moral responsibility rest. Without free will, how are we to regard ourselves, our accomplishments, and our value? On what basis can we pass moral judgements? On what basis can we incarcerate murderers? If there is no free will, then nothing is ever anyone’s “fault.” Doesn’t the whole system unravel?

No.

The specific scenario of emptying our prisons of violent criminals and letting killers and rapists off scot-free seems to be, above all else, what haunts the nightmares of compatibilists. But a moment’s consideration reveals strong reasons for why law and order makes just as much sense after we drop the pretense of free will. Whether a murderer’s rampage is the product of free will (or the compatibilists’ useful fiction of it) or prior causes external to their conscious mind, if we know someone is a danger to the public, it makes perfect sense to protect society from them. Similarly, free will is not required to differentiate between intentionality and accidents. Again, regardless of free will, we can still correctly glean that the motorist involved in an at-fault car accident is far less likely to cause future death and destruction compared to someone who intentionally plows a truck into a crowd of people. Intentions remain valuable information irrespective of where they originate.

Living in peaceful and safe communities is also rather popular, as are the policies required for maintaining them. Just because we cannot trace our desire not to live in constant fear and danger back to a will doesn’t mean those desires are not real or do not matter. A better understanding of causality does not invalidate or erase all of the things we want. But it could shift our emphasis in ways that make society better for everyone.

A justice system not built on the assumption of free will is not paradoxical. It is, however, less likely to be tinged with primitive notions of biblical retribution and punishment for its own sake, and therefore less likely to mistreat prisoners, house them in appalling living conditions, or expose them to rampant sexual assault and racialized gang violence. Without free will, we can easily rationalize incarcerating a criminal for the safety of the community, but we cannot rationalize systematically brutalizing him for no reason other than “he deserves it.” Far from stripping us of our humanity, casting off the illusion of free will reveals the humanity in everyone. For when we look at the killer, we know that there but for the grace of luck go I.

Determinism can lead down radically different roads, depending on one’s perspective. It can be seen as yanking the philosophical rug out from underneath society. It can be seen as a recipe for chaos and disorder. Or it can be seen as a more rational foundation upon which to build a more humane, ethical, and compassionate society, one that properly acknowledges the role of luck and thus takes greater care to improve the lives of those less fortunate. But change can be scary.

If your sense of morality or existential identity is moored in a fiction, then, yes, abandoning that fiction threatens to leave you rudderless. But it doesn’t mean it’s not a fiction. In the real world — not the la-la land of Jordan Peterson-style postmodernism, where “usefulness” is willfully conflated with “truth” — things either exist or they do not. Plato’s “noble lies” and Schrödinger’s Cat can’t get around this. If you don’t believe in libertarian free will, you don’t believe in free will. Don’t chicken out and try to redefine “free will” to encompass “no free will.” It’s not just silly and weak, it’s a little contemptible. More accurately understanding the world might be unnerving if it means letting go of something you’re invested in, but it reliably leads to better outcomes than persisting in self-deception. Let’s end the charade of compatibilism’s Weekend-at-Bernie’s free will. The debate is dead, and the body is beginning to smell. Just lay it to rest already.

See also: “No, You Didn’t Build That”

Subscribe now and never miss a new post. You can also support the work on Patreon. Please consider sharing this article on your social networks, and hit the like button so more people can discover it. You can reach me at @AmericnDreaming on Twitter, @jamie-paul.bsky.social on Bluesky, or at AmericanDreaming08@Gmail.com.

“Libertarians” in this context are a separate category from libertarians in a political context, although I’ve noticed a very large overlap between the two.

Determinism is distinct from predeterminism, which holds that all events and outcomes are predetermined in advance, a position not required in determinism, and probably not possible according to some interpretations of modern physics that suggest some aspects of nature are inherently random.

Smartasses might say I’m not free to believe it, which is true, though such self-satisfied quips incorrectly imply that determinism means people can’t change their minds or be convinced. We can, we just can’t ultimately control whether we find something persuasive or not.

Good piece. Well done.

What do you think about the work of Robert Sapolsky on free will?

This article comes off as childish in its description of the opposition: "the 80% of philosophers and 80% of evolutionary biologists that disagree with me are all just lying to themselves". It really doesn't help that you don't go into the weeds of what your opponents believe, either, which is pretty crucial when the premise of the article is "80% of philosophers/biologists are not only wrong, but are lying to themselves". You can't treat your position on the topic as self-evidently true when it's overwhelmingly unpopular unless your audience is only made up of people who already agree.