I wrote an obituary for President Jimmy Carter in Quillette: read it here.

2024 was something of a renaissance year for me when it comes to books. I achieved my New Year’s resolution of finding a healthier work-life balance and made the time to read more. I ended up reading 35 books, which is right in line with my usual output, though measured by page count, it’s the most I’ve read in a decade by a healthy margin.1 2024 was also the year I got back into the groove of reading fiction. For years I’d been reading only a handful of novels per year, telling myself that given my limited time, reading mostly nonfiction was simply a rational triage. Fiction was frivolous. But that’s bullshit. You can learn as much from good fiction as nonfiction. This post will include brief reviews of 22 of the books I read this year, broken down into a few categories. You can see the full list here.

Nonfiction

Science, Mathematics, and Philosophy

Conscious: A Brief Guide to the Fundamental Mystery of the Mind (2019) by Annaka Harris

This was previously reviewed in “The Unsettling Reading List”:

If someone told you that consciousness may be an intrinsic property of all matter — the concept in the philosophy of mind known as panpsychism — you’d probably dismiss it out of hand. Human experience holds that consciousness must surely arise from highly sophisticated brains and nervous systems. And yet we don’t know how, why, or when along the developmental or evolutionary scale supposedly non-conscious matter “becomes” conscious.

The early chapters of Conscious establish how little we definitively know about the mind and explore the many weird and counterintuitive phenomena that have been observed among humans (especially split-brain patients), animals, and even plants. As the book’s panpsychist thesis unfolds, chipping away at preconceived notions about the nature of consciousness, time, and identity with one argument, experiment, and observation after the next, the reader is left, not necessarily convinced, but disquieted and much less certain. 5/5

The Way of Effortless Mindfulness (2019) by Loch Kelly

Books of this sort, which are often either sniffed at as “self-help” or dismissed as “woo woo”, tend to write checks on the cover/jacket that the contents can’t quite cash. This one manages to deliver. Effortless Mindfulness provides a framework for integrating the insights and experiential states of Buddhist meditation into everyday life in a way that seems too good to be true, but remarkably, it works. The one caveat is that while the book claims to be accessible to any person at any level of experience, I’m not sure that’s true. I personally would have had no idea what to do with this guidance — and would have had little patience for unnecessary mystical terminology like “energy” and “chakras” — if I wasn’t already a somewhat experienced and well-read meditator going in. The book bills itself as a 101, but this is really 301 level stuff. 4/5

Mathematics for Human Flourishing (2020) by Francis Su

I read this hoping it might shed some light on what went wrong in my own checkered scholastic math career, or perhaps just to be inspired about the beauty of mathematics. And the book does, at times, stirringly extol the intrinsic joy of learning and recommend some useful ideas for innovating math education. It also features a moving correspondence between Su and a prison inmate whose interest in math led to a beautiful self-reinvention.

Where Mathematics runs wildly off the rails, however, occurs around the midway point, when it pivots from being a lesser Carl Sagan-esque ode to math and becomes an utterly baffling social justice manifesto. Su fills chapter after chapter with vacuous platitudes and buzzwords that reach far beyond anything relevant to the topic at hand and become a kind of cringing audition to be “one of the good ones.” Wondering why the book took such a bizarre turn, I flipped to the publication year, and sure enough, I had my answer. Published in 2020. A large percentage of ostensibly apolitical nonfiction books I’ve read that were published between 2020 and 2022 are corrupted by this same pattern — it’s become something of a red flag for me. Skip this one. 2/5

Health and the Food Industry

Salt Sugar Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us (2013) by Michael Moss

When it comes to eating habits and their impact on health, I have always leaned toward the “individual choice and personal responsibility” end of the spectrum rather than the “systemic forces” end. After all, no one will ever be as invested in your own well-being, or the well-being of your family, as you are. Yes, the companies that formulate and market processed junk food are complicit in making unhealthy dietary choices easier and more alluring than ever. But the power, ultimately, is in our own hands. I believed this long before I picked up Salt Sugar Fat, and I still do upon finishing it. But Moss has given me a vastly greater appreciation of just how overwhelming the trends and forces working against the average person are.

Limiting himself to an examination of the packaged food industry (restaurants and fast food are only mentioned occasionally), Moss breaks down the three titular ingredients that make processed foods cheap, shelf-stable, and addictive. He delves into the history behind many iconic brands and products, explores the food science and chemistry involved, and interviews dozens of influential insiders to convincingly demonstrate that the food industry has irresistibly snookered, manipulated, and hooked the public. Like a meat-eater who knows abstractly about the horrors of factory slaughterhouses but has never actually witnessed them, I knew that corporate food giants didn’t care about consumers’ health — only their money. But seeing how the sausage is made — witnessing how methodically the processed food industry has perfected the science of hacking the human brain on virtually every level — was something I couldn’t unsee.

I always appreciate books that are well-written, informative, and insightful, but I especially cherish those that expand the way I think about issues. Salt Sugar Fat did that. 5/5

Magic Pill: The Extraordinary Benefits and Disturbing Risks of the New Weight-Loss Drugs (2024) by Johann Hari

As someone predisposed to take a dim view of Ozempic and already bored with the discourse surrounding these new weight-loss drugs, I had little interest in reading a book about them. If Magic Pill had been written by anyone else in the world but Johann Hari, I wouldn’t have given it a second glance, much less picked it up. But I know Hari’s work and love his style. And, as it turns out, there’s a great deal to learn about these GLP-1 drugs: how they work, their pros and cons, and the human element involved. But Magic Pill is not strictly speaking a book about weight-loss drugs. It’s a book about the modern world’s relationship to food, starting with the author’s own affecting story and radiating outward. I found Magic Pill to be balanced, well-reported vulnerable, thought-provoking, and moving. 5/5

How Not to Age: The Scientific Approach to Getting Healthier as You Get Older (2023) by Michael Greger

The third book in Greger’s “How Not to” series (How Not to Die (2015), How Not to Diet (2019)), How Not to Age focuses on the best available balance of scientific evidence on dietary, lifestyle, and medical interventions to maximize longevity and healthy life-years. As with the prior two installments, this book contains a wealth of meticulously researched yet accessible information, however unlike its predecessors, How Not to Age could have done a better job in packaging the most actionable takeaways into a clear list of prescriptions. How Not to Age’s “anti-aging eight” — which might initially seem similar to How Not to Die’s “daily dozen” or How Not to Diet’s “21 tweaks” — were exhaustive deep dives into age-related health topics conspicuously lacking in the kinds of spelled-out recommendations most readers are probably looking for. Regardless, this book is a great resource for anyone interested in health, and very engagingly written. 4.5/5

Why We Love Dogs, Eat Pigs, and Wear Cows: An Introduction to Carnism (2009) by Melanie Joy

I found this book frustrating. It’s filled with sound arguments and appropriately disturbing accounts of the truly heartbreaking cruelty and carnage that go on in every sector of the animal agriculture industry. But time and again, Why We Love Dogs blunts its own message by needlessly miring it in a distinctly leftist aesthetic, complete with constant academic jargon, references to unrelated left-wing ideas and ideologies, and a thorough suffusion of critical social justice lingo and catchphrases.

Animal rights is an important and worthy cause — one that is not inherently political, much less leftist. If you know any NPR listeners, this would be the ideal polemic to persuade them to become more aware of animal ethics. To the other 98 percent of society, this book’s central thesis will be dead on arrival because of the manner in which it is argued. 2.5/5

Politics, Culture, and Memoirs

The War on the West (2022) by Douglas Murray

In the early sections of War on the West, a skeptical reader could be forgiven for thinking Murray is indulging in “nutpicking” — focusing on an unrepresentative radical fringe to exaggerate an argument that Western culture is under assault. Over the course of the book, however, as Murray covers case after case, many involving major institutions and people in positions of real power and influence, his thesis becomes increasingly difficult to deny. It’s easy to dismiss any individual incident discussed. It’s very difficult to honestly dismiss them all cumulatively. With exceptional eloquence and wit, Murray effectively conveys the shift and magnitude of self-hating Western cultural trends over the past decade or so. Whether anyone who is not already sympathetic to his thesis will even read this book, given his reputation and branding, is another matter. 5/5

What This Comedian Said Will Shock You (2024) by Bill Maher

I had so many thoughts about this book that I wrote a whole piece discussing it:

Yes, We've Reached "Peak Woke"

Bill Maher's new book is already incredibly dated, and that's a good thing.

5/5

Trans Figured: My Journey from Boy to Girl to Woman to Man (2018) by Brian Belovitch

I read this memoir prior to an interview I did with the author for an upcoming project (he’s an incredible guy).

Trans Figured is a harrowing, vividly colorful, and intensely moving account of how homophobia, parental neglect, and deep trauma can send someone looking for the right things but for all the wrong reasons. Belovitch’s story, going from an effeminate gay boy to a trans woman (in the late 1970s) and then later reconnecting with his masculinity, evokes the whole rainbow of emotions. Blood-boiling anger at the hate and abuse he suffered as a child. Fascination with the big-city queer scene of the late-70s and 80s. Amusement at Trish’s (his name as a trans woman) larger-than-life personality. Sorrow at the appalling circumstances and pressures under which she lived and turned tricks. And joy that, through all of the pain and anguish, Belovitch emerged happy and at peace.

What’s particularly refreshing about this book is how apolitical it is. Belovitch does not parlay his experience into any kind of political attack, agenda, or prescription. A truly remarkable story and person. 4.5/5

Losing My Cool: How a Father's Love and 15,000 Books Beat Hip-Hop Culture (2009) by Thomas Chatterton Williams

This is one of those books that has been maligned and misrepresented in many online progressive circles for the past 15 years. The book’s subtitle, combined with Williams’s reputation as a black political moderate, conveys the impression of a “kids these days” “pull up your pants” kind of Bill Cosby rant. In reality, Losing My Cool is nothing of the sort. It’s a wonderfully moving coming-of-age memoir that treads into uncomfortable territory for some, but ultimately expresses universal truths about what it means to grow, mature, and flourish as a person. The unflinching portrayal of the uglier elements in hip-hop culture will definitely rub some folks the wrong way. But I defy anyone to line up the version of Thomas Chatterton Williams recounted in Losing My Cool’s early chapters next to the version of him at the end and tell me he’s not better off. His story also underscores how much of a difference having a great father can make on a young man’s life. 4/5

The Souls of Yellow Folk: Essays (2018) by Wesley Yang

This essay collection from Wesley Yang features 13 pieces, mostly from the late 2000s or early 2010s. The title, combined with the first couple essays (which are outstanding), gives the sense that this is a book-length exploration of the Asian American experience, but that’s not the case. The subject matter ranges all over the place, sometimes covering issues old enough to now seem dated or even quaint. If there’s a single unifying thread, it’s Yang’s eloquent writing, not any particular theme. The problem is, the first two essays, “The Face of Seung-Hui Cho” and “Paper Tigers”, ended up setting a high bar the rest of the collection never quite lived up to. On the whole, I enjoyed it though. 4/5

Morning After the Revolution: Dispatches from the Wrong Side of History (2024) by

For a subject matter that’s been so thoroughly picked over (far-left social justice politics in general, and the 2020 “racial reckoning” in particular), Bowles adds something fresh in Morning After the Revolution. It’s personal, it’s on the ground, and it’s seriously funny. The freshness begins to wear off as the book goes on, but Bowles wisely keeps the overall length in check to mitigate it. As with almost all culture war writing, this will convince no one — it’s simply catnip for erstwhile progressives who weren’t down with the whole cultural revolution thing. 4/5

Fiction

(All reviews are spoiler free!)

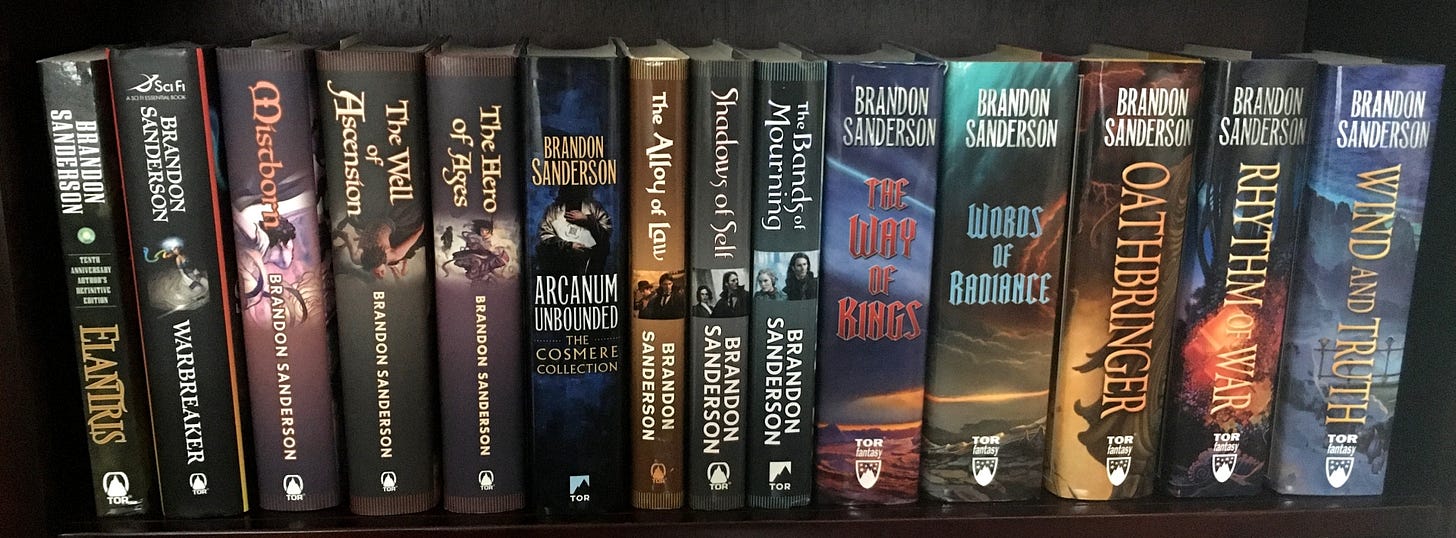

The Cosmere

As readers may know, I got COVID this past summer. It was my first time, and it hit me like no illness I’ve ever experienced. I had trouble working, could barely sleep, and was unable to concentrate on anything video- or audio-related. I basically spent two weeks holed up in my room with the windows open, letting the muggy 98° air in to stave off the chills, reading almost continuously from my favorite author, Brandon Sanderson. For those who don’t know, Sanderson writes mostly fantasy, and has risen to the top of the fantasy book world for his fictional universe (“universe” is not metaphorical here) known as the Cosmere — a vast and growing collection of interconnected fantasy series and novels taking place across times and worlds. If you can’t tell, Brando Sando brings out my inner nerd, big time. In 2024, I went on something of binge, reading 11 of his books, eight of which — Elantris (2005), The Way of Kings (2010), Words of Radiance (2014), Arcanum Unbounded (2016), Oathbringer (2017), Dawnshard (2020), Rhythm of War (2020), and The Lost Metal (2022) — were rereads. I’m in the middle of his new book, Wind and Truth (2024) right now (it’s incredible). I’ll only review the three completed first-reads here.

Tress of the Emerald Sea (2023) by Brandon Sanderson

Tress is an unassuming young washer woman from a little-known island. She can cook, she can clean, and she has a fondness for teacups. But when her friend goes missing, she embarks on an epic adventure on the high seas to rescue him. Only, on her world, the oceans are made of colorful, churning, spore-like aethers that react in extraordinary and violent ways when they come into contact with water. It’s a kind of gender-reversed version of The Princess Bride, but in an infinitely more fascinating setting and tied into the broader Cosmere. At bottom, it’s a story about what seemingly ordinary people — people without wealth, or status, or magical powers — are capable of when those they love are in peril. A big departure from the Cosmere stylistically, with a straightforward classical narrative complete with a distinct (and fabulous) narrator, Tress of the Emerald Sea is at once perhaps Sanderson’s most derivative Cosmere work while also his most refreshing. 5/5

Yumi and the Nightmare Painter (2023) by Brandon Sanderson

On a world of permanent night and neon urbanscapes, nightmares come to life and corporeally stalk the streets, kept at bay by the imagination of legions of artist civil servants armed with easels and sword-sized paintbrushes. If that weren’t wild enough, a disaffected young painter finds himself inexplicably transported to another world — one of sunlight, mystical ritualism, strict social customs, and no technology — and into the body of a captive young woman regarded as a kind of “chosen one.” The two have to work together to figure out what the hell is going on, and prevent their respective worlds from certain doom, naturally. I could go on at length about all the things I loved, but really, three words suffice to describe Yumi and the Nightmare Painter: so fucking cool. 5/5

The Sunlit Man (2023) by Brandon Sanderson

One of the neat features of the Cosmere is that it starts out as fantasy, but as time goes on and the eras shift, it’s gradually evolving into science-fiction. The Sunlit Man, set many decades after the current era of books, is essentially a preview of things to come as the Cosmere enters the space age. The story follows the mysterious Nomad as he lives life on the run from shadowy forces trying to kill him, skipping from one planet to the next. Until he finds himself stranded on a world where sunlight vaporizes the landscape every day and the inhabitants survive by continuously flying around the globe on hovercrafts. The setup for the plot is one that, as you’d expect, demands a relentless pace where the story is told at a full sprint. As fun and tantalizing as it all was, I prefer a story that breathes a little instead of being shot out of a cannon the entire time. 4/5

Stephen King

The Dead Zone (1979) by Stephen King

Like so much of King’s work, The Dead Zone is unorthodox in its pacing and structure, very heavy in its buildup, and mesmerizing every step of the way. The story follows a school teacher with a glint of extrasensory perception who wakes from a five-year coma to find himself able to see people’s past and future when he touches them. His powers send him on an obsessive quest to thwart the rise of a now-eerily familiar political phenom destined to destroy the world if not stopped. The political dimension of The Dead Zone was a particularly interesting element. (I listened to this one on audiobook, and the narration by James Franco is excellent.) 5/5

The Shining (1977) by Stephen King

The irony with The Shining is that the book is not primarily about the “shining” — the psychic abilities possessed, usually unknowingly and to varying degrees of strength, by a tiny percentage of people. Rather, it’s a psychological horror tale about a haunted hotel driving a troubled man insane. It’s hard to put into words just how much better the novel is than Stanley Kubrick’s brutally botched and criminally overrated film adaptation. The slow descent into madness is a process best explored with actual storytelling that gets inside the character’s head (King), not random and unexplained leaps (Kubrick). 4/5

Doctor Sleep (2013) by Stephen King

King’s sequel to The Shining, written more than 35 years later, is a much deeper exploration of the shining itself. Following an adult Dan Torrence (the child from The Shining), and bringing in a far larger and more interesting cast — especially the villains, a troupe of semi-immortal vampiric nomads who prolong their lives by consuming the “steam” of people who can shine — Doctor Sleep grabs you and doesn’t let go. It’s just an all-around better story than The Shining, in my opinion. (The film adaptation of Doctor Sleep isn’t bad, but the novel is still much better.) 4.5/5

Duma Key (2008) by Stephen King

The story of Duma Key is extraordinarily long in developing, and that’s actually the most fascinating part of the novel. For about the first half of the narrative, we’re not quite sure what the plot is. But following the trials and tribulations of Edgar Freemantle’s long road to recovery after a gruesome construction accident leaves him one-armed and nearly mangled, and watching as he reinvents himself as an artistic phenom, was an absolutely absorbing journey. It was only once the true story started to take shape that things, for me, went a little flat. By the final 15 percent of the book, the part that should be the most captivating, I found myself simply having to power through it as though it were assigned reading. The characters were wonderful and the premise and setting intriguing. But the specific direction in which the horror/supernaturalism went did not rise to the very high bar King usually sets in his writing. 2.5/5

Other Fiction

Siddhartha (1922) by Hermann Hesse

Siddhartha retells a fictionalized version of the life of Siddhartha Gautama (the Buddha), except Hesse splits Siddhartha and Gautama into two separate characters, each with different approaches to finding meaning, wisdom, and actualization. Exploring themes of both Eastern and Western philosophy, Siddhartha is a narrative meditation on consciousness that drills down to the core of what it means to be alive. I have no idea why they assign this to school children — few will understand it without lengthy and mind-numbing analysis, and even fewer will appreciate or enjoy it. Reading it now, all these years later, I found myself deeply stimulated and moved. You don’t need to have any grounding in Eastern philosophy going in, but I don’t think you can get the full experience without it. 5/5

Who Censored Roger Rabbit? (1981) by Gary K. Wolf

A wacky fusion of fantasy, mystery, screwball comedy, slapstick, and hardboiled detective fiction, Who Censored Roger Rabbit? is fascinating if for no other reason than its sheer novelty. Between Eddie Valiant’s laugh-out-loud inner monologue, the onion-like layers of an unfolding murder mystery, and the mind-bending world where living, breathing cartoons walk among humans, Wolf’s tale is a page-turner. The movie did as much justice to the novel as several hours on screen could, but the book is weirder, darker, and harder to peel your eyes away from. 4/5

I also read the second book (yeah, it’s a series), Who P-P-P-Plugged Roger Rabbit? (1991). Sadly, all of the fantastical weirdness and delightfully zany humor of the first book fizzled in this bizarrely disconnected second volume. Like an uninspired cash-grab movie sequel, the magic of the original was gone. Read the first book, don’t bother with the rest. 2/5

See also:

“2021: My Compelling and Rich Year in Books”

Subscribe now and never miss a new post. You can also support the work on Patreon. Please consider sharing this article on your social networks, and hit the like button so more people can discover it. You can reach me at @AmericnDreaming on Twitter, @jamie-paul.bsky.social on Bluesky, or at AmericanDreaming08@Gmail.com.

Not counting 2020, which was a special circumstance. It’s not every year the world shuts down.